Can filmmakers ever really claim to have solo projects? There are well-established dynamics to a musician splitting off from a group to make an album of their own, even when it requires a new set of supporting musicians. But while there are certain would-be purists who will insist that, say, Wes Anderson’s movies have never been the same since he stopped co-writing them with Owen Wilson, the particularly collaborative nature of filmmaking makes that line of thought sound more like conspiracy-mongering. Wilson may not have written a movie with Anderson since The Royal Tenenbaums, but he was sure on set for a lot of The Life Aquatic and The Darjeeling Limited, and Anderson has worked with so many other co-writers, recurring actors and other steady collaborators it would be difficult to describe even his most singularly Anderson-voiced movies (which is to say, all of them) as more “solo” than others.

There is an exception, though, that doubles as one of the hottest trends of the 2020s: filmmaking siblings splitting up their dual act. Josh and Benny Safie (Uncut Gems) are pursuing their own, separate projects, with Josh planning to reteam with Adam Sandler while Benny (who also acts) planning to direct another movie starring Dwayne Johnson. Lana Wachowski directed The Matrix Resurrections on her own, and her sister Lily recently announced her own debut as a solo filmmaker. The sibling duo furthest along on their divergent paths, however, are Joel and Ethan Coen. They haven’t made a movie together since 2018’s The Ballad of Buster Scruggs; Joel’s The Tragedy of Macbeth came out in 2021, and now Ethan’s Drive-Away Dolls, the first of at least two projects written with his wife Tricia Cooke, is hitting theaters. The divisions between the two films are fascinating and, at times, almost suspiciously neat.

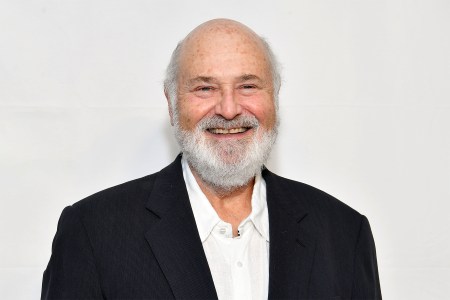

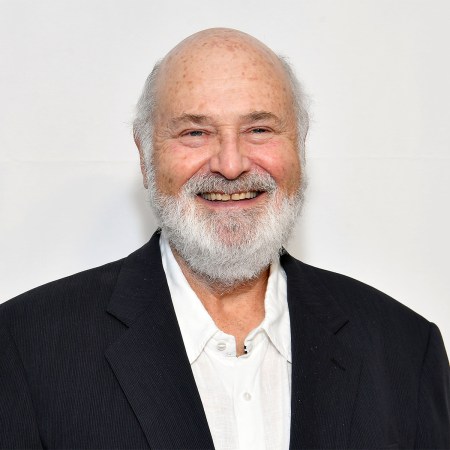

Remembering Rob Reiner, One of Hollywood’s Most Versatile Talents

The legendary director and actor, who died Sunday, made classics in nearly every genreFor the first two decades of their career, the brothers’ credits were neatly divided, too: Joel was credited director, Ethan credited as producer, and both had their names on their screenplays. (They also shared a pseudonym, Roderick Jaynes, for their work as editors.) In fact, the Coens were both doing it all, including directing, only indicating otherwise due to guild rules that discourage shared directing credits. With appropriate perversity, they made their official dual-directing debut on The Ladykillers, a remake that garnered some of their worst reviews. Viewed in close proximity, Joel’s Macbeth and Ethan’s Dolls encourage the kind of division-of-labor speculation and interpretation that the brothers have long appeared to resist. Macbeth has serious, stark portent, with hints of pitch-black comedy, while Drive-Away Dolls is chockablock with caricature, silliness and Coenesque turns of phrase that sound cribbed and warped from an old screwball comedy. The movies are easy to define by limitations: Macbeth’s adaptation of Shakespeare precludes some degree of writerly invention; Drive-Away Dolls, despite a crime-movie milieu, never gets as dark or bloody as the Coens’ past crimedies (or, for that matter, as the tale of Macbeth).

Yet both movies are more than what they lack, and Dolls is particularly instructive as a solo project. It follows the escapades of Jamie (Margaret Qualley) and Marian (Geraldine Viswanathan), lesbians in ’90s-era Pittsburgh who decide they need a fresh start. With Marian set on visiting Tallahassee, Florida, Jamie — reeling from a break-up with cop Sukie (Beanie Feldstein) — arranges for the two friends to serve as couriers for a “drive-away” service, transporting a vehicle down to Florida. But the thick, stoic man at the drive-away desk assigns them the wrong car, and they wind up absconding with a sought-after briefcase, criminals on their tail.

It’s a Coen-style crime farce with about 70% fewer complications to fill out its slim 84-minute runtime; even the central incident of mistaken identity doesn’t make much sense on its chosen zany-numbskull level. The point is for Jamie to be the uninhibited free spirit and Marian to act more reserved — which, come to think of it, reflects the images of the Coens based on their respective solo movies. That’s another way of saying that Drive-Away Dolls, like Jamie, is frequently horny. Some of the movie’s sexual slapstick has connections to notes and gags from previous Coen films, but Fargo or Burn After Reading, for example, treat sex as a vehicle for the grotesque or the ridiculous. Ethan and Cooke seem more genuinely fascinated by sex, which could have uncomfortable ramifications for a movie made by middle-aged people about much younger women. Yet Drive-Away Dolls finds a way to make its cartoonish earthiness both sexy and, at times, weirdly romantic, both in ways that would be hard to picture in a “proper” both-Coen movie. Qualley in particular embodies this quality in her physical performance — the outsized ways she angles her body to keep herself just barely covered up in racier scenes, the sly delight that creeps onto her face when the gals discover the contents of the briefcase, the obvious pleasure she takes in slinging slang that was outdated in the movie’s 1990s setting. When Viswanathan’s Marian goggles at Jamie’s forwardness, it’s not just a prim reaction; she seems scandalized by her own waves of desire.

In previous Coens pictures, desire quickly turns venal, or ridiculous. There’s plenty of that here, too, but the movie’s female point of view — including Cooke’s co-writing work on the script — allows for a little more range of desires, however smaller the actual space its fits into. This is a modest production; Coen and Cooke have characterized it as a riff on exploitation-leaning love stories from the 1970s, and its intentionally slapdash style, full of goofily abrupt scene transitions and occasional quasi-psychedelic interstitials (complete with a cameoing guest star) can feel self-conscious of its own quick-and-dirty style. Yet the movie’s later-’90s setting feels important, too; at times, the lack of exactitude in Drive-Away Dolls feels like a tribute to the post-Sundance Boom of that era, when shoestring indies (and movies with lesbian characters) were starting to make their way into something like the mainstream. Joel’s Tragedy of Macbeth was terrifically immaculate, using stark black-and-white cinematography and an expressionist staginess to achieve a singular visual atmosphere. Whether or not that makes Joel the visual stylist of the pair, Ethan goes in the opposite direction with his own solo project, favoring fast, cheap and funny. Would it be a stretch to call it punk rock?

Maybe; it’s arguable that Drive-Away Dolls has an old-fashioned view of its own quasi-provocations, or maybe Ethan is just indulging a gigglier, sillier sense of humor. (The dialogue, funny as it often is, is also less precise than the best of the Coens as a duo.) The twists of fate in this movie feel both less unknowable and less fated, even as the pieces come together with relative predictability. If Inside Llewyn Davis, about a depressed folk singer muddling through his career following his singing partner’s suicide, can be read as the Coens each grimly imagining a world without the other in it, Drive-Away Dolls feels almost like a wistful flipside for the Coen who has professed more direct weariness with the filmmaking process. (Ethan has also written prose, plays and poetry in his movie-career downtime.) It’s as if he’s trying out the idea of restarting from more-or-less scratch, just as Jamie and Marian decide to do, with equal parts unexplained capriciousness and youthful romanticism (even if Marian’s big plans for Tallahassee involve seeing her grandma and doing some bird-watching).

Of course, it’s impossible to shed those expectations completely. Ethan is still one-half of the Coen Brothers, and people will pay attention to his work, no matter how larkish his aims. That’s the closest parallel between split-up directing duos and solo albums in the pop music world: Almost anything short of Beyonce will feel the echo of absence, at least at first. Drive-Away Dolls may be difficult to replicate (though Coen and Cooke have another genre riff, also starring Qualley, in the works), and may disappoint Coens fans who find it half-baked, more akin to Intolerable Cruelty than No Country for Old Men. Yet it’s about as cheerful a breakup movie as possible — one filled with assurances that there are other paths to love and fulfillment, however mysterious and winding.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.