“What’s next?” is the most asked question in craft beer, simple curiosity cranking up to desperation in the last year or two as an oversaturated marketplace of 9,500+ breweries struggle to survive fickle consumer preferences and shrinking shelf space in retail. For as long as anyone paying attention can remember, give or take a fruited sour or pastry stout, the answer has been some variation of “IPA”: “hazy IPA,” “milkshake IPA,” “brut IPA” (a swing and a miss), “cold IPA.” But take a look at the craft beer aisle on your next grocery-store run. Could the next big thing in craft beer be…macro beer?

While they may have popped up sporadically in years past, styles more firmly rooted in macro-beer territory like light lagers and golden ales are suddenly becoming common, available from craft breweries across the country. Often, these crushable, low-ABV beers even come branded with can designs paying homage to regional lagers of decades past — your Hamm’s, your Schlitzes, your Genny Cream Ales — so there’s no mistaking it: yes, craft brewers are taking inspiration from non-craft beer. Some even package their interpretations in ways you’d expect from Big-Beer brands: 12-ounce cans instead of craft beer’s signature 16-ouncer, in six-packs, 12-packs and 15-packs.

In Cambridge, Massachusetts, Lamplighter Brewing Co. has Lamp Lager. In Minneapolis, Fair State Brewing Cooperative has Pils. In Pittsburgh, 11th Hour Brewing Co. has Eleven Eleven light lager and in Nashville, East Nashville Beer Works has Tennessee Sipper golden light ale. There’s McLighty’s Light Lager, which Zero Gravity has spun off into its own brand in Burlington, Vermont; in Covington, Kentucky, Braxton Brewing Co. did the same with Garage Beer premium lager, which comes in six-packs and 15-packs. There’s Classic City Lager from Creature Comforts Brewing Co. in Athens, Georgia, and in Toronto, Bellwoods Brewery skipped any beating around the bush with its Bellweiser pilsner. There’s a subcategory bubbling up with craft spins on Corona, like Anchor Brewing Company’s San Pancho Mexican-style lager in San Francisco and One of Us Will Have to Bury the Other, from Brooklyn’s Other Half Brewing Co. and North Carolina’s Burial Beer Co. Then, there are the brands that embraced a sessionable style and retro-leaning vibe from the start, like Gay Beer, a golden lager launched in 2018, and Nite Lite light lager, which Boston’s Night Shift Brewing Brewing debuted in 2018 but recently gave an award-winning rebrand in the nostalgic vein.

Four decades ago, craft beer was born as a response to the some of the very beers to which craft brewers are now cheekily tipping their beanies. Brewers saw variety and big flavor as an urgently needed contrast to the sameness of behemoths like Anheuser-Busch and what’s now Molson Coors. They built their scrappy rebellion on artisanal wheat beers, roasty stouts and IPAs that reached ever skyward in bitterness. The trappings had to keep pace, with 16-ounce cans to distinguish craft beers from those 12-ounce macros, and labels that became blank canvases for as much self-expression as was in the liquid. This “boldness equals creativity” ethos was shepherded by larger-than-life, brewer-as-rock-star figures, like Stone Brewing’s Greg Koch, who spoke about macro beer with the kind of passion one usually reserves for fascist governments/stuff that matters. “[W]hat big beer wants to do is remove choice,” he told Rochester, New York’s Democrat & Chronicle in 2017. “They want to homogenize and cheapen.”

When Big Beer clocked craft beer’s success and started acquiring some independent breweries, drinkers high on the David-versus-Goliath revolution felt betrayed. They boycotted Chicago’s Goose Island when it sold to Anheuser-Busch InBev in 2011, and filled Elysian Brewing Company’s Seattle taproom to buy beers and dump them when the brewery did the same in 2015. But by 2022, the industry had seen enough major acquisitions, met with all but crickets from consumers, for it to be safe to declare craft beer’s William Wallace days behind it. An industry of thousands of breweries pouring different styles to meet different preferences, and providing local gathering places with their taprooms? Sure. A drinkable method of sticking it to the man? Not so much. Maybe that’s why the craft brewers who spent their days making triple dry-hopped hazy IPAs and their nights unwinding with a crisp, uncomplicated Miller High Life finally feel safe to admit the latter is more what they look for in a beer. “My theory at one point was a lot of owners and brewers actually don’t drink craft beer, so they started cloning beers they actually drink so they didn’t have to spend money on big beers versions,” says Rick LeMunyon, a craft beer Instagrammer who cohosts Good Swill Hunting, a podcast reviewing cheap/macro beers.

What Does the Future Hold for the IPA in Vermont?

More than a decade since Heady Topper launched a global DIPA wave, Vermont brewers wrestle with the success — and identityIn Framingham, Massachusetts, Jack’s Abby Craft Lagers has witnessed the shift from craft consumers shunning light lagers to welcoming craft brewers’ enthusiastic interpretations. When they opened in 2011, lagers were a hard sell — wasn’t that Big Beer’s domain? It took years of building a strong reputation for high-quality craft lagers to show drinkers lager wasn’t the problem, but rather mass-produced lager. The more good craft lagers people tried, the more lager appreciation grew within craft. Then, says Jack’s Abby vice president of marketing Rob Day, “I think we hit a tipping point a year or so ago where it has now become common, even trendy.”

Trendy, indeed — there’s a fair chance your local brewery has installed a LUKR faucet to pour lagers the traditional Czech way. Breweries like Jack’s Abby, Wayfinder Beer, Bierstadt Lagerhaus and Notch Brewing helped craft consumers understand the beauty of a well-made lager, right when many palates were feeling hop fatigue. “Craft beer was all about EXTREME in the early 2000s,” says Day. “We shifted from traditional IPA to West Coast IPA and big-alcohol, barrel-aged beers…[then] hazy beer started rising along with smoothies and other fruit-forward beers…and now [they’re] ready to shift to something simple, subtle and delicious. That’s lagers.”

Those floodgates opening helped light lager score its invite to the craft-beer party. Influences from outside of beer factor in, too. “The overall trend toward healthier lifestyles has [led] people to seek out lower-calorie, lower-alcohol options,” says Johanna Denne, founder of All Things Alchemy brewing consultancy and cofounder of upcoming lager brand Colorful Beverage. “Light lagers fit the bill perfectly, providing a crisp taste without the excess calories or alcohol content of heavier beers.”

Craft drinkers are finally open to the possibility of light lager and similarly easy-drinking styles being good, and craft brewers are excited to show those drinkers what they can do with these styles. “I think now that the consumer has given us permission to exist in this space, you’ll see more and more innovation come to light lager from craft breweries,” says Day. That innovation usually entails approaching these intentionally simple, familiar, refreshing styles with better ingredients and brewing methods. “Brewers are as delighted by the challenge of brewing crisp lagers as we are fans of drinking them,” says Anchor’s brewmaster Dane Volek. “While Big Beer has perfected their process…[craft brewers] are chasing the expression of malt, flavors and hands-on craftsmanship, expressing our breweries’ capabilities and a more creative take on these easier-drinking beers.”

Case in point: Night Shift “prioritizes big flavors” for Nite Lite, with real corn and German hops, says co-founder Michael Oxton, using “zero preservatives, corn syrup, or artificial flavors.” He explains the brewery launched the light lager because they saw it as a “white space,” something no one in craft was touching, “yet it’s an enormous category —roughly 25% of all beer sold at retail in Massachusetts is light beer.”

“For the longest time, ‘craft breweries,’ especially microbreweries like ourselves, have stayed away from [light lagers and similar styles] to differentiate ourselves from the ‘Big Guys,’” says 11th Hour head brewer Hayden Greenlief. “However, we decided it would be a lot of fun to try our hand at a style we were so familiar with. We were also inspired by the amount of consumers coming into the brewery and using the classic line of, ‘I just drink light beer, what do you have that’s close to Miller Lite?’ Rather than push those customers away, we wanted to give an option for everyone, casual beer drinkers and super beer nerds alike.”

Quenching the thirst of not just craft connoisseurs who have more recently warmed up to lagers and lighter styles but also non-craft geeks visiting taprooms is another key motivation for brewers. “We need lots of macro-conversion beers here because there are still plenty of newer craft beer drinkers to convert,” says Anthony Davis, president of East Nashville Beer Works, who unofficially call themselves “the light beer kings of the South.”

Hop fatigue, changing trends and more demand for lower-alcohol and lower-calorie options all support light lagers, golden ales, classic pilsners, cream ales and kölsches enjoying more respect and visibility. So, why take this old-school lager love one step further with on-the-nose retro branding?

“Nostalgia is this really powerful emotion that people experience in a lot of different ways,” says Mark Hellendrung, CEO of Narragansett. “The past is usually thought about as simpler, less stressful, or a happier time.” He calls nostalgia “part of Narragansett’s identity,” and craft breweries like New York City’s Finback Brewery are tapping into that brand recognition by collaborating with ‘Gansett. Nostalgia is always at work in media and marketing — see: everything from film and television remakes to vintage fashion. Lamplighter director of marketing Emma Arnold says consumers’ interest in classic beers lines right up with their interest in old-school merch like the brewery’s “dad hats” and vintage-feel tees.

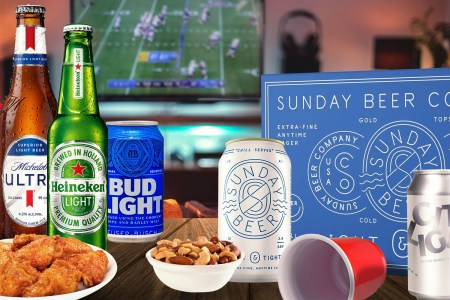

We Blind Tasted a Bunch of Light Beers to Find Out Which Was the Least Gross

How do light craft options really hold up against macrobrews, and which is the best option for your Super Bowl party?For the cans containing craft light lagers and golden ales, retro designs demonstrate brewers’ own soft spots for whatever macro lager got them into beer, or that they still turn to for thrifty refreshment. Greenlief says Eleven Eleven was inspired by the 11th Hour team’s love of Hamm’s. They reference these regional lagers by putting “Old Time, Any Time” on Eleven Eleven’s labels. Similarly, Lamp Lager, Lamplighter’s ode to Coors, Pabst Blue Ribbon and Budweiser lagers, has its own Easter egg in its description: “the sparkling wine of beers.” And of Tennessee Sipper Davis says, “We absolutely were going for the ‘Coors Banquet of craft beer,’ so embraced it with the branding as well.”

Considering craft breweries are now freely embracing these lighter, simpler styles, canning them with retro labels and often even packaging them in the six-, 12- and 15-packs of 12-ounce cans that macro beer uses to make sessionable imbibing and sharing with friends so easy, does this mean this trend is a successful way to branch out and convert non-craft drinkers? Breweries like 11th Hour and East Nashville utilize their light lager and golden ale to meet taproom visitors unfamiliar with craft beer where they’re at, but how far does that crossover appeal carry? Is it possible for a habitual Miller drinker to spot a 12-pack of craft light lager on their grocery-store shelf and give it a go? After all, this trend means craft breweries are finally brewing what the average American actually drinks, right?

“‘Lighter’ or easy-drinking styles…in the end, that’s what American beer drinkers want,” says Maureen Ogle, author of Ambitious Brew: A History of American Beer. “‘Light’ beer has always been the biggest-selling category since 1976. It spawned low-carb beers, session beers, ultra-light beers, ultra-light Premium beers, ultra-low-carb beers, ultra-low-calorie beers…It wiped out the market for plain old Budweiser and Miller High Life.”

But don’t expect all those average American beer drinkers to suddenly drop their Coors Light and dance for joy because the craft brewery in their town now has its own version. “Some people are going to pay craft prices, and most people are not,” Ogle says. As craft beer’s sales flatten, plenty of breweries are using this lighter-style, classic-branding, accessible-packaging trend to attempt to reach macro drinkers. Because, as Ogle notes, these lighter beers are cheaper to make than hop-stuffed, adjunct-packed styles, breweries can price them lower and package them economically, they may succeed here to an extent, but are more likely to retain craft consumers second-guessing their spending than woo a Bud or Coors consumer, who will still be able to get their macros cheaper than any craft interpretation, every time.

Whether the goal of converting Big Beer drinkers is there or not for different craft breweries, the trend of macro inspiration demonstrates a few key shifts in craft beer. Craft drinkers are much more accepting of these lighter styles, even thirsty for them after years of bigger flavors and stronger ABVs. Brewers can come out of the shadows and make what they’ve liked to drink all along, and they can do it better than the big guys, which will keep those craft drinkers coming back for more. And a little nostalgia is just that fun, wink-wink spoonful of sugar helping light lager and golden ale go down even more smoothly than ever.

Join America's Fastest Growing Spirits Newsletter THE SPILL. Unlock all the reviews, recipes and revelry — and get 15% off award-winning La Tierra de Acre Mezcal.