When Mark Zuckerberg announced that he was changing the name of the parent company Facebook to Meta, reflecting his focus on building the metaverse, a digital network of virtual-reality worlds, the 37-year-old CEO outlined what makes his tech conglomerate different from other tech conglomerates.

“While most other tech companies focus on how people interact with technology,” he said in a video, “we focus on building technology so that people can interact with each other.”

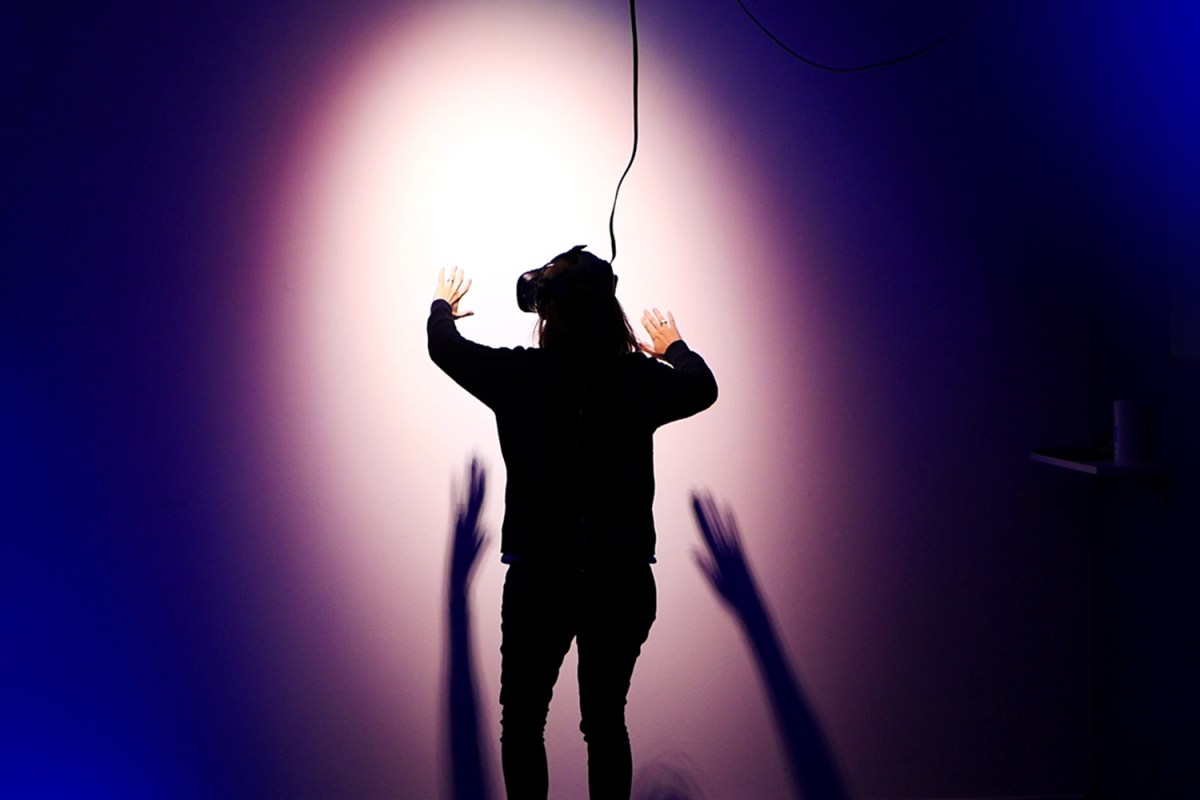

That interaction includes game playing and community building, but by attempting to replicate the real world in a digital space, it also includes the darker sides of humanity. As Sheera Frenkel and Kellen Browning detail in a new feature for The New York Times, there have already been a number of disturbing incidents of sexual harassment and assault in the metaverse.

In one incident, a 29-year-old woman was playing the VR game Population One on an Oculus Quest headset when a stranger using a male avatar “simulated groping and ejaculating onto her avatar.” (Meta owns both Oculus and BigBox VR, the developer behind Population One.) In another, a researcher recorded “sexual and violent threats against minors” while in the game VRChat. Then there is the case of the person who was testing Horizon Worlds, a game developed by Meta, who also reported being groped by a stranger.

“Sexual harassment is no joke on the regular internet, but being in VR adds another layer that makes the event more intense,” she wrote, as reported by The Verge. “Not only was I groped last night, but there were other people there who supported this behavior which made me feel isolated in the Plaza.”

“Bad behavior in the metaverse can be more severe than today’s online harassment and bullying,” writes The New York Times. “That’s because virtual reality plunges people into an all-encompassing digital environment where unwanted touches in the digital world can be made to feel real and the sensory experience is heightened.”

As the metaverse expands and the experience extends beyond headsets, the potential for harassment only increases. In fact, we’re already seeing it play out; as the Times notes, one woman they interviewed reported being groped in Population One while wearing a haptic vest “which relays sensations through buzzes and vibrations.” “[I]t just felt awful,” she said.

For its part, Meta has said it’s working to tackle these issues. One solution, as MIT Technology Review explained earlier this month, is a tool called “Safe Zone” that users can activate where “no one can touch them, talk to them, or interact in any way until they signal that they would like the Safe Zone lifted.” The problem with this, as the outlet wrote, is that it puts the responsibility for safety on the user rather than the platform.

What are the chances these new VR platforms can be developed in a way that’s safe for all users? It doesn’t look promising, considering the plan seems to be building them first and figuring out the harassment problem later.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.