Editor’s Note: RealClearLife, a news and lifestyle publisher, is now a part of InsideHook. Together, we’ll be covering current events, pop culture, sports, travel, health and the world.

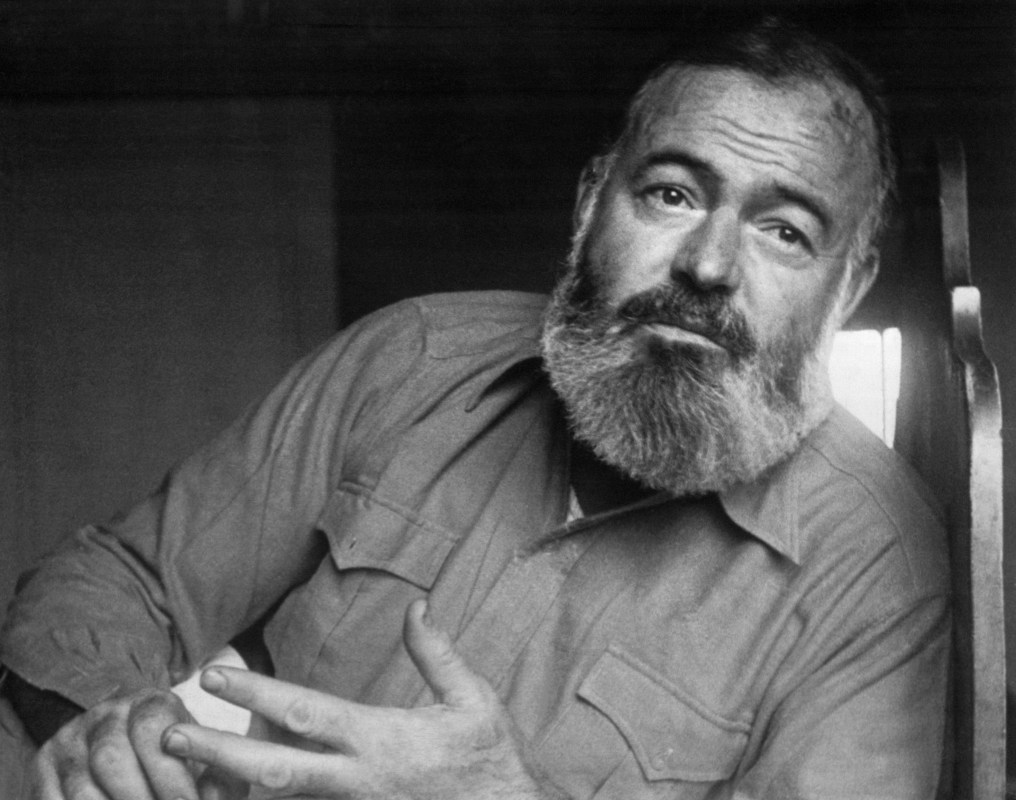

If you’re reading this, there’s a solid chance you know who Ernest Hemingway is. But Ellen N. La Motte? Probably not.

It’s safe, however, to assume that Hemingway knew who La Motte, a World War I nurse and writer, was. According to a new report from The Conversation, La Motte may have helped pioneer the style of writing for which Hemingway is best known: sparse, understated and declarative in the face of overwhelming wartime scenes.

La Motte wrote a collection of stories in 1916 based on her experience working at a French field hospital on the Western Front titled The Backwash of War. And she did it long before Hemingway left home to volunteer to drive an ambulance in the conflict — a role that led him to write A Farewell to Arms in 1929.

“There are many people to write you of the noble side, the heroic side, the exalted side of war,” she wrote. “I must write you of what I have seen, the other side, the backwash.”

But her book was quickly banned in England and France because La Motte — an American — made honest and unflinching criticisms of the war, regardless of a rave review from the New York Times that said her stories were “told in sharp, quick sentences” that bore no resemblance to conventional “literary style” and delivered a “stern, strong preachment against war.”

It is therefore time to return The Backwash of War to its proper perch in the pantheon of war writing, argues The Conversation. It’s a seminal work, and deserving of the same high praise that Hemingway has long enjoyed from critics and readers alike.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.