Journalistic excellence can take many shapes, as we saw this week. One great example featured a sit-down with Oscar-winning actress Gwyneth Paltrow, who has now become an enormously successful CEO—and brand—in the health and wellness industry. Other instances involved the investigative prowess of both NPR and The Guardian, both of which unveiled dangerous, unfair working conditions among our nation’s middle class. Then there was the rare, behind-the-scenes look of what really happens at the NFL combine. And finally, we got a historical deep dive of Roosevelt’s New Deal and what it actually accomplished, which was then juxtaposed with the new House majority Democrats’ proposed Green New Deal.

Gwyneth Paltrow might have won an Oscar—although some may think it wasn’t deserved—but there’s no debate that Paltrow has said she felt she was “masquerading as an actor.” Now, as the face and chief executive of Goop, she is using her celebrity to grow her controversial passion project into a $250 million powerhouse brand. The businesswoman channels her late father, producer Bruce Paltrow, who died in 2002, when trying to strike a balance as the leader of her company. “My dad was a benevolent, tough Jewish boss,” Paltrow told The New York Times. “He was very loved for the most part, and he gave me a template for how one leads.” Read more to see how she believes every start-up, even an overwhelmingly male operation, is “full of feminine energy.”

When a natural disaster strikes an American city, there are agencies with funds ready to act. These organizations are full of people whose only objective is to help people get back on their feet, out of the rain and into a livable situation. But in these dire situations—catastrophic events that could, theoretically, act as an equalizer between the haves and the have-nots—a new report uncovered that biases still exist all across the country, and that some disaster victims enjoy help in a number of ways that others do not. Read this troubling NPR investigation on how white and wealthy Americans often receive more federal relief dollars after a disaster than the poor and minorities do.

There has been a century-long war to remove lead from American buildings and other infrastructure. And while the campaign has been successful on a few fronts, a lack of regulation, political will, and government funding, as detailed by The Guardian, has meant that contaminated drinking water still plagues many public spaces—including our schools. This is particularly dangerous because continued exposure to high doses of lead can affect the development of a child’s brain and nervous system as well as impair their IQ, academic achievement, and even ability to pay attention. While cases like the water crisis in Flint, Michigan, have received isolated attention, the vast scale of the problem has been swept under the rug for years, even though experts have released numerous studies on lead’s hazardous effects. Until now.

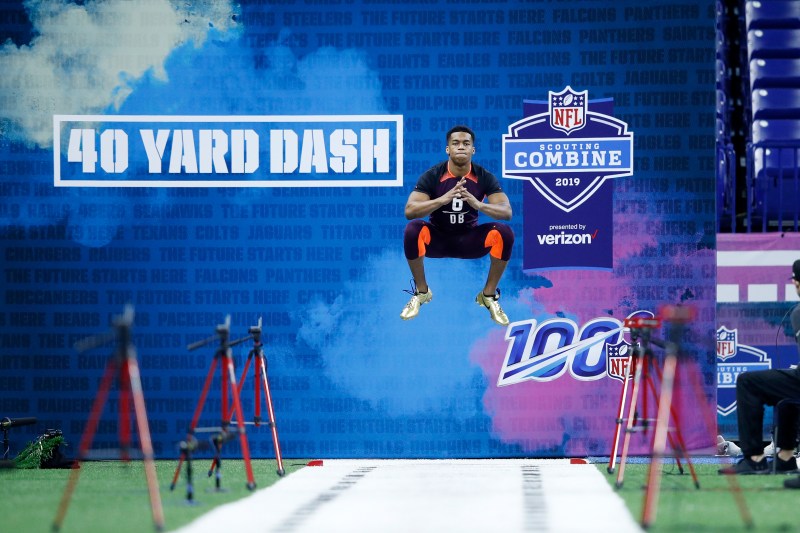

The NFL combine—a showcase of strength, speed and overall athleticism by college prospects hoping to make it big come draft night—is rapidly becoming a huge media event itself. So much so, that one ESPN reporter found a shroud of secrecy now surrounds many of its details. The combine is a televised show with real futures at stake, but many of the suite-sitting GMs don’t really want to be there, so distraction abound. Follow along this story for a backstage pass to a week full of shrimp cocktail, booze, loose lips and anonymously told truths about the players, owners and one of the NFL’s fastest growing spectacles.

As progressive Democrats begin a political push for a Green New Deal, one reporter revisited how President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s original New Deal came to pass and how it worked. This historical exploration, published this week in The Atlantic, comes from, appropriately, a historian: Louis Hyman, a professor at Cornell University. While conservative politicians are warning of catastrophic federal debts from the proposed expenditures and liberals insist that a top-down federal program is crucial to success, Hyman argues that neither are precisely correct because they both overlook the key role private investment played in the New Deal’s political architecture. Independent, outside agents, he claims, helped propel FDR’s landmark legislation and cement its lasting legacy—and should be the model for any new version laid out by ambitious young members of Congress.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.