On June 6, 1962, 60 years ago this week, the very nervous, almost-Fab foursome of John, Paul, George and Pete entered EMI’s studios on Abbey Road in the St. John’s neighborhood of London for their first recording session under the recording contract that the already legendary producer George Martin had offered their rather green manager, Brian Epstein, on the label he was then managing, Parlophone, when the pair had met the previous February. But the group — who were tearing up the pub and club circuit in the north of England after a long, grueling stint in Hamburg, Germany, where they’d played eight hours a day, six days a week, honing their craft and becoming one of the tightest and rawest bands in the country — nearly didn’t make the cut during that first session.

Paul McCartney’s bass amp was found to be so inadequate that a replacement was cobbled together from speakers pilfered from the famed studio’s echo chamber, and John Lennon’s tiny Vox amplifier had to be held together with string to keep it from rattling, as the engineer Norman Smith recalled to me during an interview in 2007. Finally, Smith, who went on to produce the legendary recordings by the early, Syd Barrett-fronted Pink Floyd, was able to get a suitable sound on tape.

Still, amplifiers were the least of the Beatles’ problems that day. As they ran through “Besame Mucho,” the 1940s hit written by Mexican songwriter Consuelo Velázquez, plus their originals “Love Me Do,” “PS I Love You” and “Ask Me Why,” it became clear to all in attendance that, while it was far from a sure thing that guitar groups would be the next big thing, this group surely wouldn’t make the cut with their current drummer supplying the backbeat.

“There Pete Best was coasting along, a good-looking lad in a great group, and that could’ve been it forever,” recalls Mike McCartney, the photographer, recording artist and, of course, Paul McCartney’s brother. “But for the decisions that were made, which were necessary, of course.”

A couple of the tracks from the day were included on Volume 1 of the Beatles’ Anthology compilation, released in 1995, and the evidence is plain: Handsome fan-favorite or not, Best couldn’t keep a beat to save his life.

“I always felt sad for Pete, until the Anthology,” McCartney says. “Then, for the first time, he saw some real money, which was important to me, because he was never looked after. And to lose that crew, and to lose out on fame too, that was awful.”

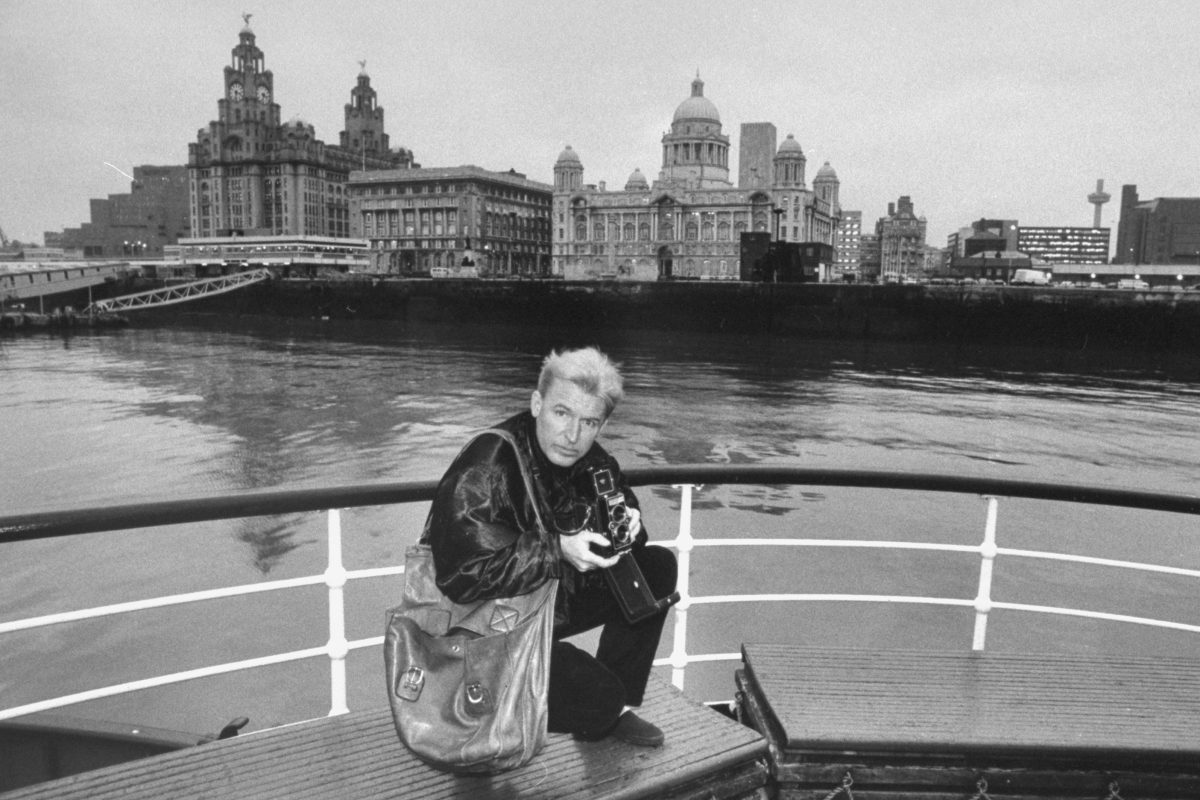

It’s all recounted in rich reminiscences and stark, candid photographs by the brother of one of the world’s most famous men in Mike McCartney’s Early Liverpool, recently released by Genesis Publications in a gorgeous, limited-edition deluxe book. But McCartney recalls the time of Best’s firing, in the summer of 1962, particularly vividly.

“Brian Epstein came along and thought, ‘Okay, I love you in your leathers, but this is a business, and if you want to make a million, then you’ve got to change your look,’” he says. “I remember John Lennon, particularly, but certainly heard, ‘if you want to make a million.’ They went to the tailor Dougie Millings and bought those first suits, and I remember my brother coming home with a box, and I opened the tissue paper and there was a mohair suit. I said, ‘What are you doing? We said we’d never go along that route.’ And he’d already worked it what to tell people. He said, ‘Look, ours have velvet collars.’ Oh, dear God. And so, there’s a photo in the book at the Tower Ballroom, and there’s Pete in his suit. And then, in the next photograph is Ringo, in the same suit the next week. Poor Pete had been let go. And he had to pay for the suit!”

Of course, Martin heard something on those tapes, and he recalled to me during a conversation in the early ’90s that, while there was no sign of the songwriting prowess Lennon and McCartney possessed, he was, more than anything, enamored with the band’s quick wit and camaraderie. And so, just 90 days later, they were given a second chance. With a new drummer in tow and a fresh batch of songs — picked by Lennon and McCartney, rather than Epstein — with which to impress Martin, the rest, as they say, is history.

As obvious as the band’s trajectory all seems now, in hindsight, Mike McCartney remembers 1962 as a fraught rollercoaster of a year, one that saw the Beatles nearly splinter apart more than once, if not for an enormous amount of tenacity and a large helping of Liverpudlian luck.

“Fate could have been different,” he says. “They might’ve gone down to London, done the record with George Martin, and then what if nothing happened and it didn’t sell? Ringo would have gone back with [his pre-Beatles band] Rory Storm and the Hurricanes, and the rest of the Beatles would have had to get jobs and maybe gone on doing music in their spare time or whatever.”

As McCartney sees it, whatever came before, 1962 was the true beginning of the Beatles, at least as popular culture now knows them. As he was learning his craft of photography in his spare time, his brother was making leaps and bounds as a musician and songwriter — the result, as he sees it, of doing nothing but learning to be a Beatle. It was a year that the band kept up a grueling live schedule, made the first of several hundred BBC radio appearances, signed that all-important record deal with George Martin (who would go on to become a crucial collaborator for the band) and ditched Best for the man who put the beat in the Beatles, Ringo Starr. But they also lost the man who McCartney recalls as the soul of the early Fabs.

“Stu Sutcliffe was John’s mate,” he remembers. “I knew him because I wanted to go to art college, too, where he and John were studying. He had a style to him. And a real presence about him. He looked cool, and when they started the group, he was trying to play but he just couldn’t. My brother was trying to trying to teach him. But that’s hard, trying to learn an instrument like that. But John wanted him in, and so he had to learn. Then, when they went over to Hamburg he met Astrid [Kirchherr, the photographer] and fell in love. He told them, ‘Well, you get on with it. Paul can go on the bass. I’m staying here doing me art.’ But he was really important to the group up to that point.”

Later, not long before he died in April 1962, Sutcliffe visited his former group in Liverpool, with Kirchherr on his arm.

“He was looking thin and pale, and he must’ve been taking medication, because, like the letter from him reproduced in the book, which is very James Joyce-y and surreal, he was sometimes just floating, and then all of a sudden, he wasn’t,” McCartney recalls. “There’s a picture in the book of Astrid, with her very short, Mia Farrow-type hair, John and Stu outside the Cavern. Not long after that, we were all down there, in the Cavern, and I remember Stu and Astrid walking in, and Stu had this ordinary jacket, but without the collar. We all pissed ourselves laughing. He was not happy, because we didn’t get it, the style. But then, when he died, those famous Beatles collarless jackets, they’re in homage. They weren’t Beatles jackets. They were Stu’s jacket.”

The Beatles took his death hard, says McCartney, most especially John Lennon, who he recalls had a unique bond with his former art school classmate.

“He was a nice bloke, and very quiet,” he says. “Even onstage, he just stood there, in these very dark, beautiful shades. He couldn’t have seen a bloody thing. But he looked so good. And I always remember how cool he was to be around.”

It’s all there in Early Liverpool, from family photos and Teddy Boy poses from his teenage brother Paul, to run-ins with the actress Jane Asher when his brother brought her to Liverpool for the weekend in 1965, and much more — both mundane and astonishing, but all of it chronicling a time and place that now seems so magical because of its inhabitants.

“All they were was my brother and me mates,” McCartney says with a laugh, as he flips through the photos he took all those years ago now reproduced in a massive book. “That’s all they were. It was just me learning photography, and my brother doing the same thing in music. Really, that’s all it was.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.