Almost every major music tour announced this year has followed the same pattern: Concert is announced. Around four sets of presales happen, none of which get you access to any seat that’s reasonably priced or in a good location. When the actual announced ticket sale day arrives, seats are several hundred dollars above the advertised price — most likely due to the advent of dynamic pricing (because you always wanted the concert industry to resemble the travel industry!) or already-sold tickets snatched up by bots and brokers are now being “resold” on the secondary market for inflated prices (which, if you’re Ticketmaster, is something you now have some control over).

So like everyone else, you wait until the day of show and hope StubHub comes through.

Until that day, you will seethe, because there are no perfect solutions. Consider that potential ticket-reselling legislation was recently opposed by former Ticketmaster enemies Pearl Jam because it blocked some positive elements of the secondhand market, like transferrable tickets. There are also startups like Cash or Trade that promise secondhand tickets at face value, but lack inventory. Some bands (like Radiohead) have limited ticket sales to individuals and forced concert-goers to match tickets with identification, which effectively deters scalpers, but can also be a headache for all involved.

And it looks like we’re still far away from using some more advanced technological solutions. “I’ve heard talk of blockchain being incorporated into the ticket process, but I don’t know enough about that to really make an educated statement,” says industry vet Michael Stover, an award-winning musician/producer and founder of the music promotions company MTS Management Group. Stover thinks that dynamic pricing is a good model, but also supports artists like Adele who have partnered with independent ticket agencies, or even more extreme measures like the ones taken by the late Tom Petty, who sometimes retroactively canceled tickets purchased for resale.

Even when bands try to do the right thing, they suffer. Rage Against the Machine held back 10 percent of their tickets so they could charge extra but give the additional funds to various nonprofits, but were still met with fan hostility over lack of ticket availability and prices that sometimes started at $190 for 300-level seats (the band eventually added more shows to meet demand). My Chemical Romance ditched fan pre-sales, but Ticketmaster’s dynamic pricing and a virtual queueing system meant people ended up paying hundreds of dollars for tickets that were supposed to start at $59.

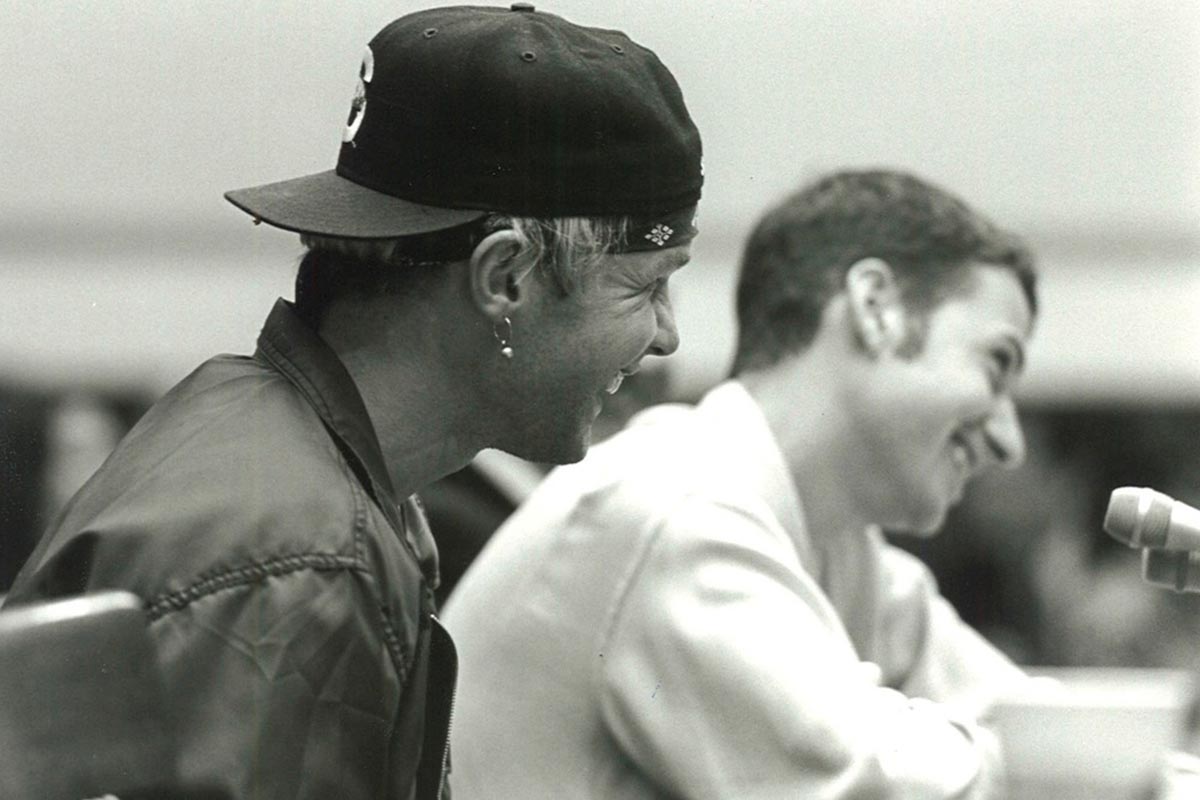

Since there’s no one solution — or at least not a good one — we spoke with Dean Budnick, editor in chief of Relix and co-author of Ticket Masters: The Rise of the Concert Industry and How the Public Got Scalped, about a few different ways to improve the secondary market.

InsideHook: Are concert tickets actually priced too low, as Live Nation’s chief executive recently suggested?

Dean Budnick: I don’t think consumers feel that way. Ticket prices have increased steadily over the past few decades. The average price of tickets to the 100 most-popular U.S. tours rose from $25.81 in 1996 to $91.86 through the first half of 2019.

However, it is true that tickets to certain shows sell on the secondary market for many times their original price. So an argument could be made that in those instances, tickets are priced too low. However, that mostly applies to the best seats to the most popular shows. But there are other considerations beyond pure economics; for instance, there’s also the question as to whether artists want tickets as high as possible, which certainly prices out portions of their fanbases.

It’s rumored that up to 40% of the available tickets for big shows never even get offered to fans. Is that accurate?

What’s important to remember is that the old-school, 9 a.m. Friday on-sale is really a thing of the past. These days concerts have any number of pre-sales, often through the artists’ own fan clubs, credit card offerings, the venue and promoter’s email lists and the like. Many of the people buying these tickets certainly are fans, but they’re fans who have figured out the best way to work within the system. I can understand why this can be frustrating, though, for individuals who expect that the bulk of the seats will be released during the official on-sale.

Has any artist, promoter or ticket agency come up with a good solution to price gouging on secondary ticket markets?

I’d go all the way back to the Grateful Dead, who sold 50% of the tickets to their shows through their own mail-order service and limited the number of tickets that folks could purchase. The Dead hired full-time staffers to oversee this process and at times some of these staffers would spread the envelopes out on the floor to check the handwriting and ensure that no one was ordering too many seats and then sending them to different addresses.

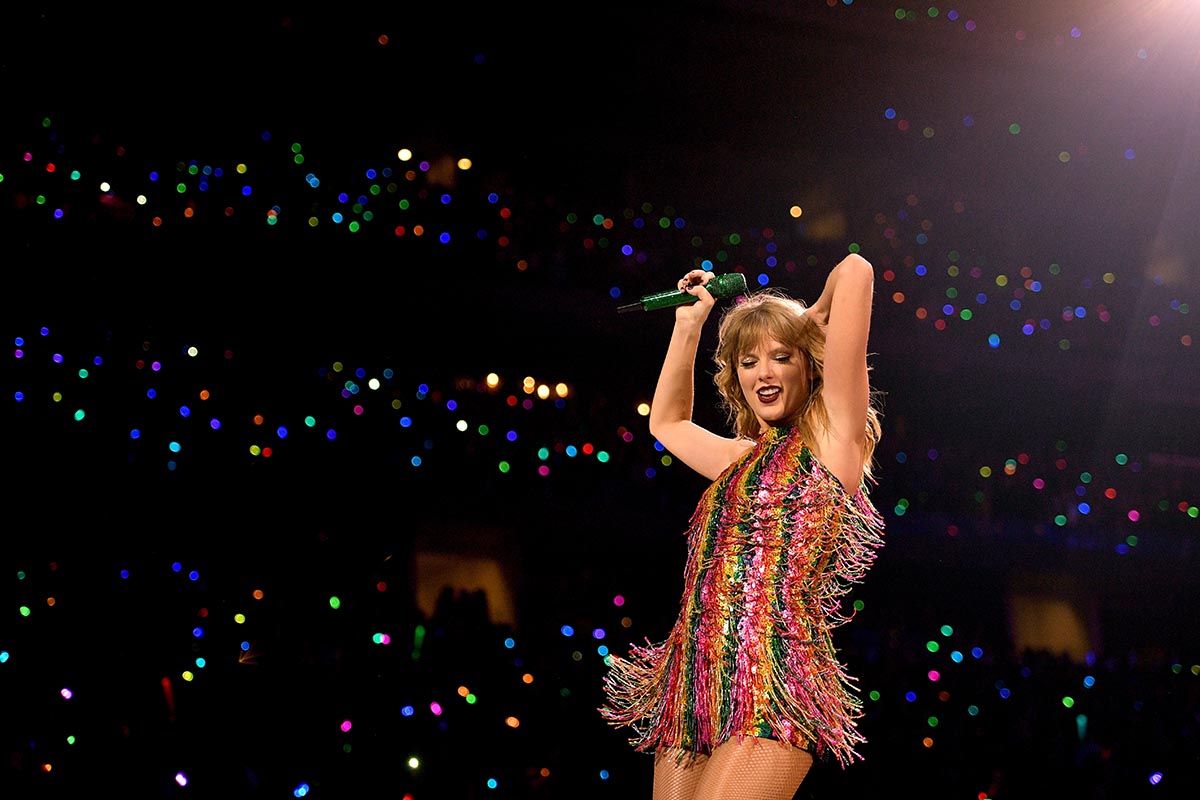

More recently, I think Taylor Swift has made a good faith effort to combat this. Her slow-ticketing model acknowledged that it wasn’t important to announce a sellout in 10 minutes, which in the past could be a point of pride or a marketing tool. Instead, she meted out tickets to a given show in the weeks and months leading up to a show, so that fans knew they wouldn’t have to resort to the secondary market. More recently, she has utilized the Verified Fan program, which is an attempt to counter bots by requiring people to register with Ticketmaster before on-sales.

Is there a technological solution to keep out bots or ensure that the everyday fan has a better chance at getting tickets?

It’s tricky. My suggestion, for national tours, is to limit the ability of folks to purchase tickets to shows within a certain geographic range. This can be accomplished through the zip code on a credit card and/or ensuring the IP address of someone buying tickets is within a certain radius. It’s something that the Nashville Predators have implemented in some form over the past few years during the playoffs, to fend off incursions of Chicago Blackhawks fans.

Will this solve the problem altogether? No. But it will make it easier so that folks aren’t buying up tickets on the other side of the country or the other side of the globe with the intent of flipping them on StubHub. It’s that additional pressure of part-time ticket scalpers not just the professional brokers that has added pressure over the past few years.

What did you think of Tegan & Sara’s solution to shifty resellers? (Editor’s Note: The duo re-sold tickets they saw on secondary markets at the door in a pay-what-you-can scenario, with proceeds going to the band’s nonprofit arm).

I think it’s awesome. From a logistical standpoint, though, that could be tough for artists performing in larger venues on extended tours. It also could be tricky in dealing with promoters when grappling with financial guarantees in the deals confirming shows.

I also would point out that given the fact that so many artists are supporting themselves by touring revenues these days, it theoretically could have a negative economic impact. Of course Tegan & Sara have such a special relationship with their fans that I doubt they lost revenue or even cared too much about that. As they stated, they just wanted to have fans attend that show rather than play to an empty house, because seats were not selling on StubHub.

In a somewhat analogous manner, for many years U2 held back tickets to their arena shows and then sold them at the box office a few hours before each of their dates, which is another way to combat the issue on some level.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.