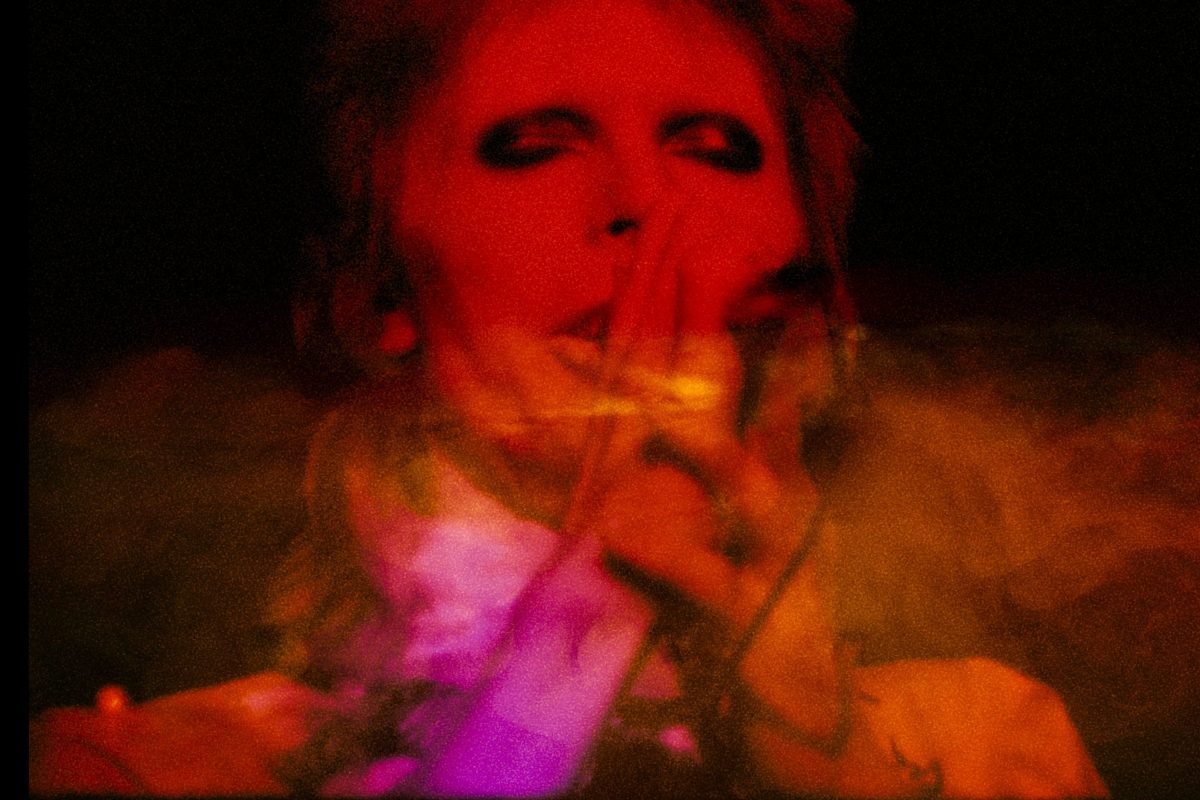

Brett Morgen’s Moonage Daydream — his documentary about the creative life of David Bowie, out everywhere this weekend — is a remarkable achievement. It redefines the rock doc, and perhaps the documentary itself, taking viewers on a non-stop rollercoaster ride through Bowie’s art.

In fact, while not at all a chronological telling of Bowie’s story, by using a treasure trove of unseen footage and clever audio mashups behind a non-linear narration from Bowie himself, Moonage Daydream does nothing less than turn the burned-out format of the music documentary on its head. And, like much of Bowie’s work, that non-linear yet easily comprehensible approach creates an artistic assault that’s at times bombastic, while still remaining subtle and intelligent enough that it will surely have fans chewing over the wealth of little Easter Eggs — not to mention those countless bits of unseen footage and unheard audio — for years to come.

But perhaps that’s no surprise. Morgen’s work includes the heartbreaking Kurt Cobain documentary Montage of Heck, as well as the excellent, anarchic Rolling Stones doc Crossfire Hurricane, not to mention The Kid Stays in the Picture, the animated Chicago 10, and, as part of ESPN’s 30 for 30 series, June 17th, 1994, about that fateful day in the O.J. Simpson saga.

Below, Morgen discusses how he got the job to direct the first authorized David Bowie film since the icon’s untimely passing, what he thinks about the (few) naysayers, and what drove him to make a rock and roll documentary unlike any that’s come before.

InsideHook: I know you had met with David about a different project before his death. But then, five or six years ago, did you get a call asking if you wanted to make this film? You’re not a traditionalist documentarian, and they knew Montage of Heck, I’m sure, and your other films, so when you first got the brief, did you have a vision in your head? Did you know you didn’t want talking heads explaining David Bowie? Did you have the sort of onslaught of images and sound that Moonage Daydream became rattling around in your head?

Brett Morgen: Actually, I wasn’t hired. I forced myself upon the Bowie team. Because, before I even knew I was doing Bowie, after I’d finished Montage of Heck, I decided that I wanted to try to create a non-biographical musical experience for IMAX. It was really simple. I felt that IMAX theaters offered the greatest sound system that has ever existed on planet earth. And so, how great would it be to go in there and just listen to music and have a sort of visual sort of razzle dazzle? And that was it. It really was about growing up going to science museums, because they’re all dark at night, and my memories of going to them as a kid. So, I had this fantasy that I could take over those spaces and do a six o’clock Zeppelin show, a seven o’clock Beatles show, an eight o’clock, you know…

You’re talking about back in the ’80s, I guess, going to the local planetarium for Dark Side of the Moon?

That was where this all came from. I will tell you the two most formative experiences that fed into this was when the film of Pink Floyd’s The Wall came out, when I was 15, I was at the perfect age. I saw that film five nights in a row on acid at the Fox Theater in Westwood. And I spent nearly every weekend in eleventh grade at Griffith Park observatory. On acid. And those were the greatest experiences of my life, outside of my children and my family and everything. At that age, it was wild, man.

The Wall is a dark fucking movie to see on acid.

You want to know the strangest thing I’ve ever seen on acid? Repo Man! Opening night! We had no idea what that film was; had never seen a trailer. There was almost no one else in the theater, again, at Westwood. There were seven of us. And if you think about that film, and the weirdness of that film, that thing fucked us up.

Anyway, I think I’ve wanted to make Fantasia my whole life, but I’ve been bogged down by narrative. I wanted to do something purely experiential that didn’t have to be explained. I believe in emotional truths; I don’t believe in facts. And I certainly don’t go to the cinema to learn facts. I go to the cinema to have a sensory, visual experience. And I like to create art that’s specific to the medium it’s that’s being built for. So if you can do it in a book, why do it in a film? The idea of doing interviews in a theatrical space, I just don’t understand. That should be a book, at least for the most part. With all due respect to the people who knew Bowie, I don’t really want to see them talking on an IMAX screen. That’s not what that space is for.

And, I’m guessing, neither would David, and I think that’s really the crux of it.

Now we’re coming full circle. So, I started off with this idea of doing just these interactive IMAX music experiences. I’d met with David and his team in 2007. And after David passed, I said to them, “I’m doing this thing. It’s a musical experience. It’s non-biographical. I’d love if you’d allow me to consider Bowie.” And they told me that David had saved everything. That he’d been working with an archivist for 20 years, although with no sort of endgame. And the one thing that they knew was that he didn’t want to participate in a traditional documentary. And so, I’d come along with, I think, kind of the perfect proposition. And I think it certainly helped that I had sat with David about this other project. At the end of the day, in my original meeting with David, there must have been something he responded to. And so, they gave me permission to have final cut and access to everything. And the only condition was — because David’s not here to approve or authorize the film — that it was never going to be Bowie on Bowie. It was going to be my impression of Bowie. So, I spent a year reading everything I could about Bowie, and that gave me context when I was looking through the footage. And then, a year to the day David died, I had a heart attack, flatlined, and went into a coma. And when I came out of that, I began to discover, not just an amazing artist and creative genius, but a guy who had a real philosophy about art and what he did. And I have three young children. I was going through my own existential crisis about how to rebuild my life. And suddenly, I found that David became my rabbi. He was kind of offering me the wisdom and a sense of purpose that I couldn’t find elsewhere in life. And that’s where the film started taking on this totally different dimension. And I realized I had an opportunity to create a roadmap for how to lead a balanced and fulfilling life, creative life and spiritual life and life, as a father and a husband in the 21st century during this age of chaos and fragmentation. So this was very personal. It has completely transformed my ideas and the way I want to approach my art and my life from this point forward. It was just incredible.

And the critical response, as well as the response at early screenings, I understand, has been phenomenal. Although it’s your idea about who David Bowie is and was and what he meant, it also leaves a lot up to the viewer, taking in all the rapid-fire information you give them for over two hours, to figure a lot of that out for themselves, in a creative format that I have no doubt David would have approved of.

Well, thanks. But, you know, there’s been, like, three people that I’ve read that had a hostile reaction. And, ultimately, they were people who thought they understood Bowie better than me. And my response to that is, you know, give me a little credit. I saw everything. This is my report from seeing everything. And I have to tell you, also, that I take no offense. I feel sort of sad that they weren’t able to allow themselves to have that opportunity. Because, if you’re a Bowie fan, who the hell wants to have talking heads telling you about information you already know? They mentioned that I didn’t include Lou Reed or Iggy Pop. But if I show it to my 13-year-old, who doesn’t know about Lou Reed or Iggy Pop, they’re not asking me. They’re not saying, “It seems like there’s something missing.” And seems to me that if you get Bowie, as soon as that Nietzsche quote comes on at the beginning of the film, you’ve got to understand that this isn’t biographical. It’s going to be something other, and I’m reaching for the stars with this film. And you may not like it. You may think it’s bombastic. You may reject my idea. But to review this film or critique this film through the lens of a biographical documentary is, to me, just kind of ignorant.

So I know you want to encourage people to see this in a proper theater. The IMAX experience is crucial. And I was thinking, I know Giles Martin a bit, and this film feels like what happened with Love.

That was my inspiration! You can thank him for me, because the idea to do the IMAX music experience really originated when I saw Love. I had no interest in Cirque de Soleil, but the third time I saw the Love show, I closed my eyes, listening to that music, and I felt like I was hearing it for the first time. I know that there’s purists out there who may have an issue with that, but I don’t. I’m like, “Hey, if you want to hear the original mix, you can go listen to the original mix.” But if they can give me some sort of new entry point to music that I’ve loved, God bless them. I’m all there for it. I love when Dylan was releasing those albums with 150 outtakes. I love those. They’re amazing. Especially the Infidels one that they recently did. So, the Beatles Love show was a real inspiration, because I wanted to have discreet sounds. I wanted to be able to turn that way and hear the guitar and go that way and hear the bass, so that’s how I approached my mashups. And then, at the mixing stage, everything we did was from stems. We weren’t remixing. We were making the music up. We were starting from scratch. And sometimes you can’t even hear the narration. The mix dangerous. It’s going to fall off the tracks at any second. I don’t care. It’s just texture. “I don’t need to hear that line.” There’s a couple weird little audio pieces that I forgot to mute when I was locking picture, and they’re still in there. So you may be like, “Wait, what’s that?” But as you know, with David, there are no mistakes. There’s just happy accidents. It needed to feel spontaneous and unrehearsed and organic.

One last thing: I noticed, during the credits, that you created the mashups. Are you a frustrated musician? Because, even if you’re not, that had to be a really exciting endeavor.

I am not musical at all. But experience of making the mashups — and the stems I worked from — were incredible. Especially from Berlin. Because as I got to the stems from Berlin, and I would open up a track, and then I’d put on another track, it was cacophony. It wasn’t until all the tracks were up, that I’d be, like, “Oh, my God. It’s magic.” Because here’s the thing about Bowie: I pick up a deck of cards, I throw it on the ground, and it’s a fucking mess. Bowie comes in and he throws it on the ground and it’s a fucking castle.

I would love to circle back with you in 10 or 15 years to see what havoc you wrought with the creative kids who are now 15 years old, who are going to see this film. Because I think it’s really going to inform them, like when you see a great rock band at 15.

I’ll leave you with one little tidbit. I haven’t talked to anyone else about this. So, I said I’m not going to do any more music films from this point forward. But I do have one in the can. I’m not doing anything forward from here. But there’s another thing that is done, that everyone will be completely blown away by, I think. So, you’ll just have to wait and see.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.