The true face of the Jericho Skull, a 9,500-year plastered skull that is the oldest portrait in the British Museum’s possession, has been reconstructed.

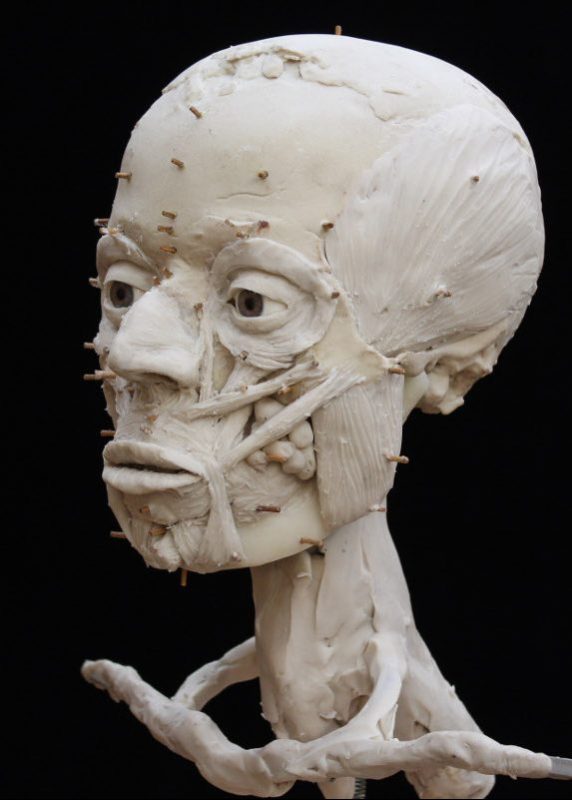

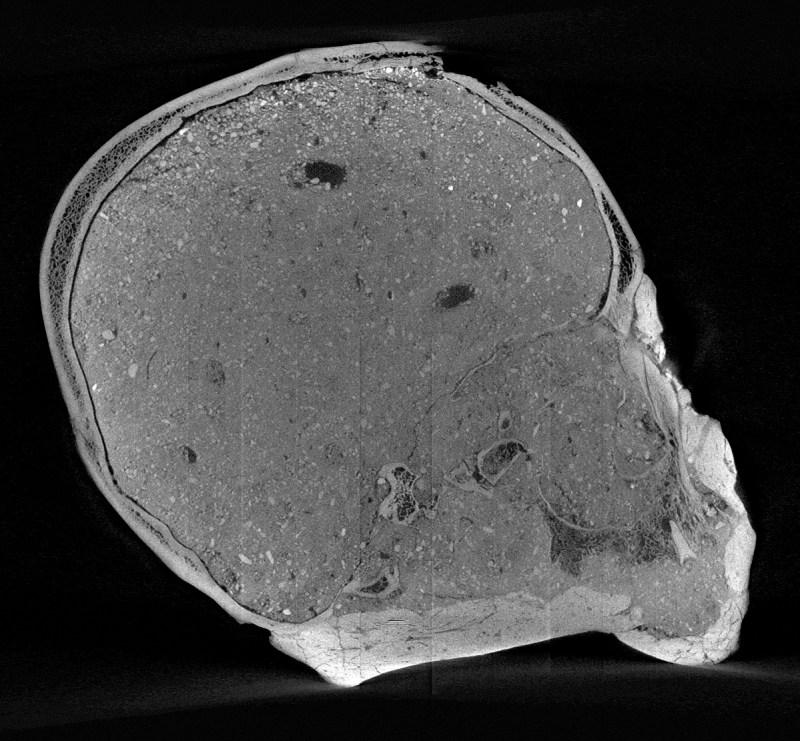

This reconstruction was handled by the Natural History Museum’s Imaging and Analysis Center, whose micro-CT scan of the skull laid the groundwork for a 3-D digital model of it that, for the first time, revealed the shapes of the skull’s palate, cheekbones, brow ridge, and eye sockets. From there, researchers were able to put together what they feel is an accurate representation of the man’s facial features.

The Jericho Skull was originally found by archaeologist Kathleen Kenyon in 1953, and is one of seven. Kenyon found the skulls near the Jordan River, in the West Bank of what is now Palestine.

Plastered skulls—made by removing the skull of a dead person and sculpting a “face” on it with plaster—were an important Neolithic ritual, but the exact reasoning behind it is still a matter of debate. The practice has been linked to the worship of elder males, assumed to be a type of portraiture of high-status citizens, or simply based on the shape of the deceased’s skull. Whatever the case for plastering a skull was, it was performed with great reverence.

In the case of the Jericho Skull, researchers found that he lacked a lower jaw (which may have been removed for the plastering process), as well as broken teeth and a healed broken nose. They also saw evidence of tight head binding, often applied to children for aesthetic purposes during that time.

Other details of the man’s face, namely his hair and eye colors, are still unknown, and can’t be accessed yet without damaging the rest of his skull. Still, the current reconstruction is on view in the British Museum until February 19, 2017.

—RealClearLife Staff

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.