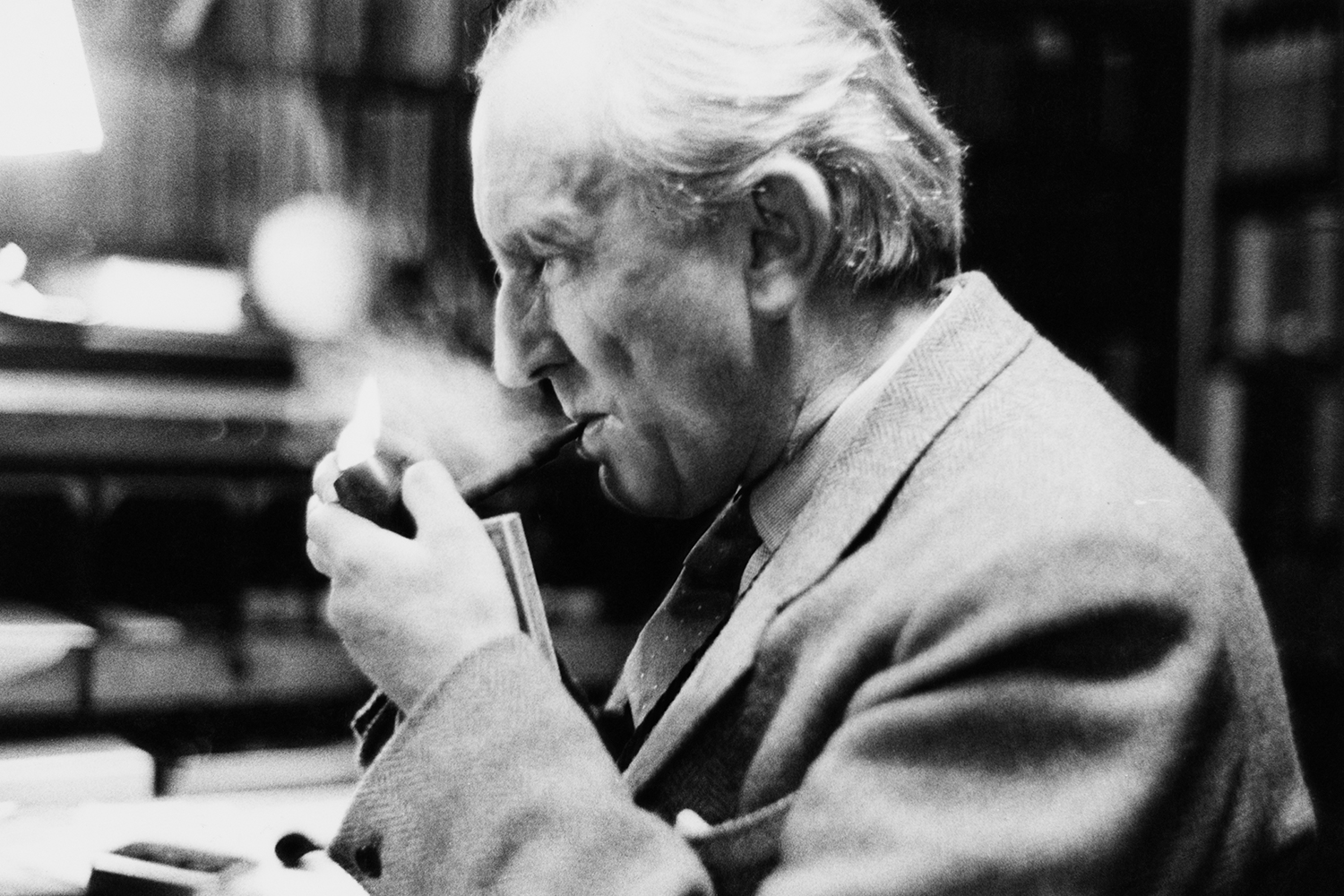

A new age of Middle-earth has begun: the Age of Amazon. On September 1, the new series The Lord of the Rings: The Rings of Power begins its rollout on Prime Video. Much is being made of its budget (it’s being called the most expensive television series ever) and the particulars of the characters and plot (the writers are going off script from J.R.R. Tolkien’s works), but what about the backstory behind it all? If you’re curious about the conditions under which this seminal fantasy realm was born, revisit our story on Tolkien’s experience serving in World War I, with insights from expert historians.

The fandom around J.R.R. Tolkien is like Minas Tirith, that colossal tiered city of Gondor. On the bottom level are the fans of Peter Jackson’s Lord of the Rings movies, which are celebrating their 20th anniversary this year, as The Fellowship of the Ring was first released on December 19, 2001. On the second level are those who have read the main novels, including the source material for this trilogy and The Hobbit. To make it up to the third level, you must, in my estimation, read the seminal essay “On Fairy-Stories.”

As celebrated Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger writes, the essay, originally conceived as a lecture Tolkien presented in 1939, is the author’s “definitive statement about his art.” It’s a substantial discussion of how he defines the genre that encompasses The Lord of the Rings, one much more specific than our modern conception of fantasy, as well as a criticism of those who place the genre in the children’s section. (“If fairy-story as a kind is worth reading at all it is worthy to be written for and read by adults,” Tolkien wrote.) “On Fairy-Stories” is also one of the rare instances where Tolkien hints at the brutal, biographical reality embedded in his fictional realms.

“A real taste for fairy-stories was wakened by philology on the threshold of manhood,” Tolkien wrote, “and quickened to full life by war.”

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was born in 1892 and thus was in his prime when World War I broke out and Britain entered the fray in 1914. In school at Oxford at the time, he joined the service after he graduated in 1915 and, after months of training, quickly found himself in “one of the deadliest battles in the history of the world,” as Lora Vogt, curator of education and interpretation at the National WWI Museum and Memorial, tells InsideHook. That would be the Battle of the Somme, which would last nearly five months in 1916 and end with more than one million wounded or killed, with Tolkien taken out of commission by trench fever.

Despite these formative, traumatic experiences, as Vogt says, Tolkien “rarely affirmed” that he directly drew inspiration from them for his stories of Middle-earth. Yet, a century after the end of the Great War, almost 70 years after The Fellowship of the Ring was first published, and 20 years after the films expanded the book’s already colossal influence, it’s clearer than ever that the timelessness of the War of the Ring is inextricable from the author’s service in the Great War.

One place where Tolkien was clear about direct inspiration was Mordor, the blighted land on the edge of the continent where the volcano Mount Doom spews ash and the Dark Lord Sauron watches from Barad-dûr. “He was highly explicit about the fact that his experience in the Battle of the Somme is and was very influential in his creation of Mordor, the burning, the charred landscapes, all of that,” Vogt explains. But the entire experience of that consequential campaign, from the mundane logistics of warfare to the “mental strain,” she says, are infused throughout the novel.

To understand the horror of the Somme, a conflict named for the French river and fought between the British and French armies against the Germans, Vogt says it’s helpful to compare it to D-Day, the World War II offensive that many people land on when recalling “the bloodiest battles ever.” As Jonathan Casey, director of archives and the museum’s Edward Jones Research Center, explains, there were close to 60,000 British casualties, of which nearly 20,000 were deaths, on July 1, 1916, the first day of the battle.

“It takes several days of D-Day to equal the same level of casualties of the first day of the Battle of the Somme,” Vogt says. She adds, “Tolkien, his battalion is going to be at [German defensive outpost] the Leipzig Salient, which is basically in the center of the battlefield. So he’s at one of the worst places in the midst of one of the worst battles of history.”

Casey and Vogt rifle through all manner of influences that stem from this experience. Seeing friends and enemies dying in the water led to the Dead Marshes, the ones Frodo Baggins and Samwise Gamgee are led through by Gollum. The devastated landscapes, ones previously populated with trees and forests, are manifested in the concern of the Ents. The British military classification of a batman, or an officer’s personal servant, can clearly be seen in Sam’s character. Even in Peter Jackson’s movies there are elements that find their source in the war instead of the books; as an example, Vogt says the director used puttees, long strips of cloth soldiers of that era wore wrapped around their leg from the ankle to the knee, in costuming for the fantasy movies.

That type of Easter egg (with regard to the puttee) and logistical know-how (w/r/t the mechanics of warfare) aren’t the elements that keep viewers returning to the movies and readers to the books. The enduring appeal more likely stems from Tolkien’s own sense of duty in Word War I — one where “he was expected to [serve]” and “served honorably,” as Casey says, but ultimately “was glad to be out,” an opinion undoubtedly shared by his protagonist Frodo — and even more so, his experience of the bonds of friendship that are forged in times of great peril.

“One has indeed personally to come under the shadow of war to feel fully its oppression; but as the years go by it seems now often forgotten that to be caught in youth by 1914 was no less hideous an experience than to be involved in 1939 and the following years,” Tolkien wrote in the forward to one edition of The Fellowship of the Ring. “By 1918 all but one of my close friends were dead.”

That quote has often been extracted, as has the one from “On Fairy-Stories,” to prove that The Lord of the Rings was inspired by WWI. What often gets left out is that Tolkien dedicates much of this foreword to dispelling the notion that his tale is “allegorical” or even “topical,” whether we’re talking about his wartime experience or the closer-to-publication events of WWII.

“The prime motive was the desire of a tale-teller to try his hand at a really long story that would hold the attention of readers, amuse them, delight them, and at times maybe excite them or deeply move them,” he wrote.

If you ask Vogt, who has worked at the National World War I Museum and Memorial for a decade and can see the parallels between Tolkien’s experience and the millions of soldiers who fought alongside him, she’s deeply moved by one thing in particular.

“It’s the fellowship. It really is the fellowship,” she says. “If you’re watching the movie, it’s so moving at the end … the importance of that friendship with Samwise Gamgee, and this structure of male friendship in particular, of doing something amazing that nobody else can connect to, and how that changes them, and how that changes them both for the better and for the worse. I’m getting the tingles on my cheeks right now. One of the most beautiful parts of [Tolkien’s] writing is that emphasis on fellowship. He certainly had friends before World War I, but I think it really brought that home.”

As Vogt was speaking during our Zoom interview, I also got tingles in my body just thinking about the ending of the movie version of The Return of the King, when Frodo leaves Sam, Merry and Pippin behind. On the surface, it’s a scene in a fictional fantasy movie between hobbits, elves and a wizard. Underneath, it’s a parting among friends who have gone to hell and back, just as Tolkien did, and as some of his close friends failed to do.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.