Welcome to The Workout From Home Diaries. Throughout our national self-isolation period, we’ll be sharing single-exercise deep dives, offbeat belly-busters and general get-off-the-couch inspiration that doesn’t require a visit to your (now-shuttered) local gym.

There’s a bit in the late-’90s comedy Big Daddy where Adam Sandler throws a stick in the middle of a path in Central Park to trip up an in-line skater. It’s standard Sandman slapstick, but the subtext is abundantly clear: Rollerblading is lame.

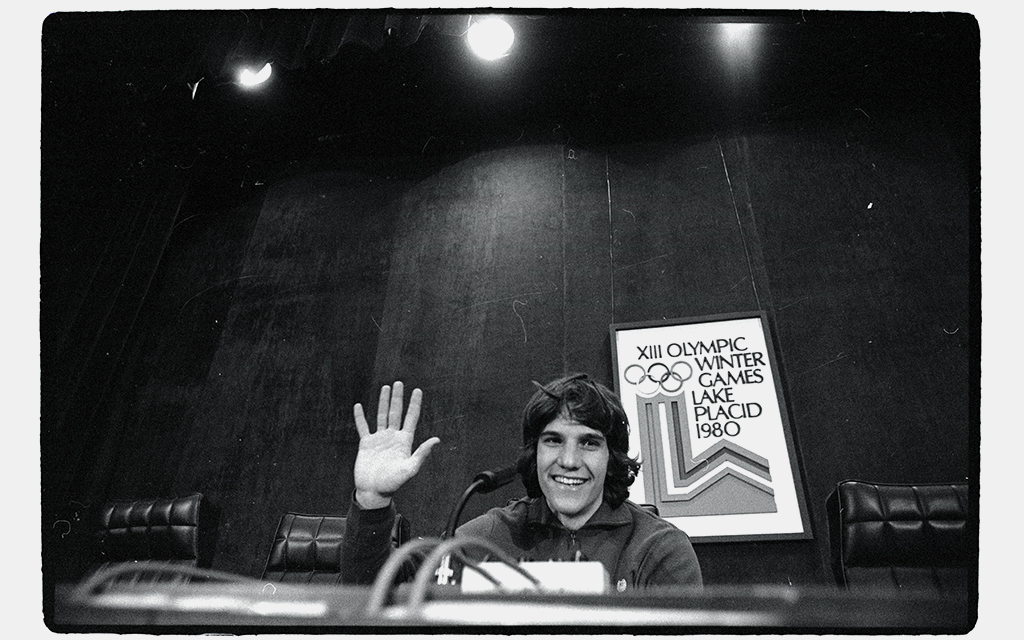

That movie came out in 1999. The year before, X Games IV in Mission Beach, San Diego, hosted four different inline skating events. Around the same time, a well-known activewear shop in Chicago called Londo Mondo was selling $10,000 worth of inline skates a day, most of which could be seen on sunny days along the LFT. In 1995, a cult classic Power Rangers movie opened with a three-minute shot of the superheroes Rollerblading around Sydney. Decades before that, a peak-career James Caan played a stoic inline skating star in a dystopian sports flick called Rollerball, and over in real life, a man named Eric Heiden was captured in LIFE magazine training for his speed-skating events in the 1980 Olympics with a pair of roller skates. He went on to win five gold medals.

By then, America had long been fond of quad-wheeled roller skates. They were worn in “skating marathons” around city streets in the 1930s (the New York edition began in Washington Square, and ended all the way up in The Bronx’s Starlight Amusement Park) and later served as footwear for waitresses in diners across the country in the 1950s. Roller skates were an about-town pastime even before that: a gripping photo of a young woman roller skating past suffragists protesting President Woodrow Wilson’s White House was taken in 1917.

When inline skates arrived in the 1980s, a sleek, modernized style with two to five wheels arranged in a single line, the country was ready. A company called Rollerblade, Inc., founded in Minnesota in 1982 as Ole’s Innovative Sports, was the only inline-skate maker to secure worldwide distribution, and rode that privilege to overnight ubiquity. By the early ’90s, there were few neighborhoods in North America without at least one pair of Rollerblades, and by 2000, 22 million Americans were strapping on Rollerblades (or a pair from one of the brand’s competitors) at least once a year; by contrast, only 17 million Americans reported playing baseball in that same year.

But the aughts weren’t kind to the activity. Sales slipped across the board as the craze fizzled out; the 634% growth that had fueled inline skating from 1987 to 1995 simply wasn’t sustainable. A man named Allan Wright, who’d quit his day job in 1997 to start the world’s first inline skating tour company, Zephyr Adventures (long-distance skating was a thing, and so was extreme long-distance skating — just years before, an Englishman named Jason Lewis had completed the first solo crossing of the United States on inline skates), had to reconsider his entire business. Wright’s skating offerings weren’t so intense, of course, but they quickly became démodé. He had to pivot to include biking and wine tours, a big reason that the operator is still around today.

Elsewhere, Nike gave up on Bauer, a skate purveyor it had purchased in the ’90s, the 2005 X Games didn’t showcase a single inline-skating event, and roller hockey leagues got used to lighter signup sheets. In 2010, the Sporting Goods Manufacturers Association reported that the number of inline skaters in America had fallen by 64 percent. It was over.

Fads come and go in America. We all have a drawer somewhere with a fidget spinner. But when that time arrived for Rollerblading, it wasn’t enough for the once universal diversion to go quietly into the night. It needed to be put in its place, too.

Big Daddy shot the first spitball. Then Aziz Ansari appeared in a viral Funny or Die video with a bit of woefully dated homophobia: “They say the hardest thing about Rollerblading is having to tell your parents that you’re gay.” Dos Equis’s “Most Interesting Man in the World” struck the final blow, in 2008. After 18 seconds of lead-up, in an advert titled “On Rollerblading,” he finishes chatting with two women, turns to the camera, and says, firmly: “No.”

The story might’ve ended there. According to a 2019 report from The Guardian, a stunning number of Rollerblades have ended up in Nairobi, where Kenyan youth race on superhighways at rush hour, and various clubs compete against each other. But then, this is America, land of second chances and cyclical fashion. Nothing’s ever truly gone. Recently — which is to say, the last several weeks of lockdown — inline skating has seen a stunning resurgence. Bauer recently reported a 723% year-over-year traffic increase on customers searching for inline skates. Propelling the comeback? A return to Rollerblade roots. When single-line-wheeled skates were originally introduced, they were intended as an offseason training tool for athletes who made their living on the ice, particularly hockey players.

As ESPN pointed out earlier this week, the only NHL players who currently have access to ice rinks either possess special, rehab-related permission … or are Swedish. (Sweden, you may have heard, is approaching social distancing a little differently.) When Wayne Gretzky and Alex Ovechkin recorded their first ever joint interview earlier this week to discuss Ovechkin’s quest to eclipse Gretzky’s goals record, Ovi also asked The Great One what he would do, if he needed to stay in shape during a suspended season and couldn’t get on the ice. Gretzky replied: “I would try to find places to Rollerblade as much as possible.”

The redemption arc for Rollerblades, it appears, is well underway.

NHL players have scrambled to acquire pairs (Bauer has arranged shipments to almost 100 of its top athletes) and those who were successful haven’t been shy about posting them on social. Some of these posts have depicted functional training — like the striding stick-work practiced above by Detroit Red Wings prospect Joe Veleno — but many others have depicted Rollerblades as a casual accessory to lockdown life. There are skates going out for a couple laps around the block, skates causing trouble around the house, skates pushing baby strollers. The truce between a long-lampooned fad and the resident frat boys of American sports spawned from necessity, but there is real love there, and it might (might) just be enough for Rollerblades to be cool again.

Which, really, is a good thing. This rebirth can — and should — go beyond antsy hockey pros, and deserves a larger audience than the grunge pioneers who’ve been quietly bringing the sport back in skateparks across Canada for a few years now. Because the truth is, inline skating is a unheralded form of low-impact aerobic exercise, and could prove a legitimately beneficial allocation of your time during an unceasing lockdown. According to Harvard Health Publications, a 185-pound person can expect to burn 311 calories during 30 consistent minutes of roller skating; that’s more or less in line with 30 minutes of running at a 12-minute mile pace (which will burn 355 calories).

The American Heart Association recommends healthy adults get at least 150 minutes of cardio exercise a week. Consistent cardio lowers your blood pressure and cholesterol, reduces risk of osteoporosis, strengthens the lungs, helps you fall asleep and facilitates blood flow, which improves mood and boosts productivity (whatever that word may mean for you). An extended cardio routine can lead to a longer life, and importantly, more high-quality years as that life plays out. But it’s not always as simple as committing to cardio; your body needs various options to avoid injury, and your brain needs aerobic diversity to avoid boredom.

Inline skating is oddly, ideally suited for this moment. Rollerblading coaxes more effort out of the glutes and the core (pushing, balancing) while demanding less of the joints. You can cruise for an extended period of time and work up a casual sweat, target hills to test resistance, or try a HIIT-reminiscent practice known as “interval blading,” which involves repeats of all-out sprints and rest. The latter might take the exercise out of the cardiovascular zone, but it will further diversify your weekly workouts and give you an understanding of what pace is officially uncomfortable. Word to the wise: when you do try to go faster, get low. Bend the knees and pump the arms.

Of course, now that roller skates are sitting at the cool table in the cafeteria again, they’re a little hard to come by. If you don’t still have a pair in the garage, I’d recommend picking up a beginner’s go-to from Dick’s while they’re still in stock. They’re going for $99. You may be able to find a pair in your size at Bauer for closer to $200, but don’t count on it. Pure Hockey, meanwhile, has perfect sizing available on skates priced at $1,200, which just feels unhelpful.

Two weeks ago, a friend of mine texted our old college group chat, completely unprompted,”I’m buying rollerblades, can anyone talk me out of this investment?” I’m proud to report he got a bunch of iMessage “exclamation point” reactions in return. At one point while writing this piece, I looked out the window at an empty street, feeling a little extra trapped, as certain afternoons during the quarantine have gone, when a man tore through the frame. He was wearing Rollerblades, and he looked happy. There wasn’t a stick in sight.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.