I was jogging the end of a four-miler late last week when I spotted my elementary school gym teacher running on the other side of the street. She’s probably interacted with 5,000 kids since the early 2000s and I hadn’t seen her in years, but there was still enough recognition for us to each wave and call out a hello.

Growing up, I was fortunate enough to avoid the shame-and-pain gym class nightmares of Freaks and Geeks lore. My gym teacher didn’t humiliate kids who couldn’t scale the climbing ropes or arm 10-year-olds who were already stealing their dads’ Coors Lights with dodgeballs. She was approachable, genial, ubiquitous; we’d see her every year at the town’s Memorial Day 5K and Fun Run. She taught us how to play four square, jump rope like Rocky and ride around on butt scooters. There were no mandated meshy uniforms, and while sweating was a priority — I’m from New Jersey, where at least 150 minutes of health, safety and physical education are required per week, per grade, and going beyond that limit helps school systems earn awards — we also learned bizarre activities like speed stacking.

In retrospect, speed stacking (a game where kids pile a bunch of cups on top of each other as fast as they can) was a harbinger of shifting attitudes in physical education. It signified a retreat from exclusively celebrating the same feats of strength and agility that were already on full display at recess, or in Pop Warner and Little League on the weekends. Skills like speed cups, hula hoops, scout’s knots and tag noodles were noble attempts by American gym teachers to bring other athletic skills like strategy, communication and teamwork to the fore.

There was one practice, however, that contradicted this new approach to youth fitness until the 2012-2013 school year, when it finally met its quiet, little-reported demise. I speak of the Presidential Fitness Test, the infamous multi-day annual assessment meant to determine the strength, speed and flexibility of the country’s unwitting, unwilling bairns.

Way back in the 1950s, an Austro-Hungarian physical educator named Dr. Hans Kraus developed a 90-second fitness evaluation with his colleague Sonja Weber of the New York Presbyterian Hospital. It involved a series of six different movements which tested for basic strength and flexibility. Dr. Kraus eventually teamed up with Bonnie Pruden, an American mountaineer, to administer the test to schoolchildren around the United States; the pair would watch as children tried to raise their feet while lying on their backs, or bend forward to touch the floor while their knees were kept straight. Proper completion of these moves, along with the four others, proved enormously difficult for most young Americans. Of 4,458 children between the ages of 6 and 16 tested over a span of seven years, 58% failed.

Dr. Kraus and Pruden were able to present their somber findings to President Eisenhower in 1955, after a well-connected Philadelphian named Jack Kelly — who’d won Olympic gold in rowing three times in the 1920s — brought them to the White House for a luncheon. Willie Mays was in attendance, along with Jack Fleck (a golfer who once beat Ben Hogan in the U.S. Open) and a 25-year-old Tony Trabert, who’s now a member of the International Tennis Hall of Fame. They shared the numbers written out above, alongside a kicker: Dr. Kraus and Pruden had also administered their test to children in Italy, Austria and Switzerland, and the European tots had a significantly lower failure rate, at just 8%.

This didn’t sit well with Eisenhower, who, according to an ensuing Sports Illustrated article titled “The Report That Shocked the President,” promptly recalled his apoplexy during World War II that more than 50% of American men had been unfit for service (it should be noted here that 20% of those men were rejected for illiteracy). Fearing that the nation was turning soft, Eisenhower established the President’s Council on Youth Fitness in 1956. Just a year later, it debuted the first ever iteration of the Presidential Fitness Test, which was closer in DNA to the NFL Combine than Kraus and Pruden’s simple assessment. It included pull-ups, sit-ups, the standing broad jump, the shuttle run, the 50-yard dash, the softball throw and the 600-yard run.

How did Eisenhower leap from an ahead-of-its-time test meant to measure functional mobility to a mini field day? America was at war, again. The Korean War had just ended, the Vietnam War had just begun, and most high-ranking officials in Washington, even those in charge of something as trivial as adolescent athleticism, were forever influenced by their experiences in WWII. The exercises they chose were those familiar to the nation’s cadets: the agility needed to storm a beach, the throwing strength needed to toss a grenade into a trench. These “events” could be easily quantified and administered by anyone; the Kraus-Weber test, meanwhile, required a measure of medical discernment.

In 1960, President-elect John F. Kennedy penned an op-ed in Sports Illustrated suggesting his administration would continue the Presidential Fitness Test as it was, and make a special effort to combat an onslaught of “softness” amongst American children. He wrote:

“Throughout our history we have been challenged to armed conflict by nations which sought to destroy our independence or threatened our freedom. The young men of America have risen to those occasions, giving themselves freely to the rigors and hardships of warfare. But the stamina and strength which the defense of liberty requires are not the product of a few weeks’ basic training or a month’s conditioning. These only come from bodies which have been conditioned by a lifetime of participation in sports and interest in physical activity. Our struggles against aggressors throughout our history have been won on the playgrounds and corner lots and fields of America.”

The name of Eisenhower’s original program changed under Kennedy, to the President’s Council on Physical Fitness, and under President Lyndon B. Johnson to the President’s Council on Physical Fitness and Sports. (Today, it’s called the President’s Council on Sports, Fitness and Nutrition.) Lest it ever lose any attention or credibility, presidents often assigned famous sportsmen or sportswomen to function as chairman of the council: President George H.W. Bush famously appointed Arnold Schwarzenegger from 1990 to 1993. This, plus the introduction of an actual award for excellence on the test — the Presidential Physical Fitness Award — compounded its de facto standardization all the way through the late 2000s, when gymnast Dominique Dawes and quarterback Drew Brees were named co-chairs.

But by 2013, the test was disbanded, with organized fitness at school tending more toward meaningful cooperation and less toward quantitative assessments of speed and strength. A visit to an HHS.gov page devoted to the test now features the heading “What happened to the President’s Challenge?” It turns out the federal program has rebranded as the Presidential Youth Fitness Program, a health-related initiative with participation from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the Amateur Athletic Union (AAU), meant to function as a helpful, barometer-style check-in on the fitness of students. The U.S. Army was notably not consulted, and though gym teachers haven’t returned to the Kraus-Weber test, they now assess more forward-thinking attributes like aerobic capacity or body composition. Results (which boil down to Healthy Fitness Zone, Needs Improvement or Needs Improvement – Health Risk) are shared confidentially with students and parents. Nobody gets a certificate Hancocked by the president.

While the decades-old padding beneath elementary school basketball hoops will likely stay the same, gym classes, which leave lasting impressions on all students, must continue to evolve. It’s not an easy ask, balancing mindless fun (lava tag) with upsetting facts (18.4% of American children between the ages 6 and 11 are obese), especially when gym class rarely receives enough attention or funding to greet the dilemma head-on. But we’re headed in the right direction, and I was pleased while researching this piece to learn how American officials have finally grappled with the hawkish history of the country’s physical education system.

At the same time, though, the fitness nut in me felt a slight, silly pang of loss. Despite the Presidential Fitness Test’s twisted history and excessive mission, there was something messy and beautiful and uniquely American in its inefficiency. I decided, fueled by nostalgia and quarter-life competitive fury (I passed my elementary school on that four-miler too, I should note), to give it a proper send-off, and see if I still had the chops to hang around with the cool kids.

This past weekend, I completed the entire Presidential Fitness Test, in its final, 2012 iteration. The softball toss was long gone, and the test had been whittled down to the following: curl-ups in a minute, the mile run, max pull-ups, the 30-foot shuttle run and the V-sit and reach. Below, find my results, and an explanation of how to perform each stage of the test. One boon I’ll say, right off the bat: while this sort of examination is unhealthy when delivered to a group of 10-year-olds, it’s a novel, harmless way to discover what you’ve got left in the tank, whether you’re 30 or 60. Just make sure you stretch up beforehand, and hit a massage gun when you’re done.

Curl-ups in a minute

The Presidential Fitness Test was famous for strict regulations on correct form, which may be a rare positive for its legacy. Poor form is all too common at the gym (I still struggle to throw a kettlebell around properly) and often leads to injury, so that’s one aspect of military-inspired fitness that the test was actually right to dig its heels on. It’s just … the exact form the test requires for its curl-ups in a minute challenge is a bit odd. You’re supposed to cross your arms across your chest with palms resting on the opposing shoulder. Your feet should be held down against the ground by a partner, and only 12 feet out from your butt. Your partner gives a countdown, then hits the clock, and you’re off to the races.

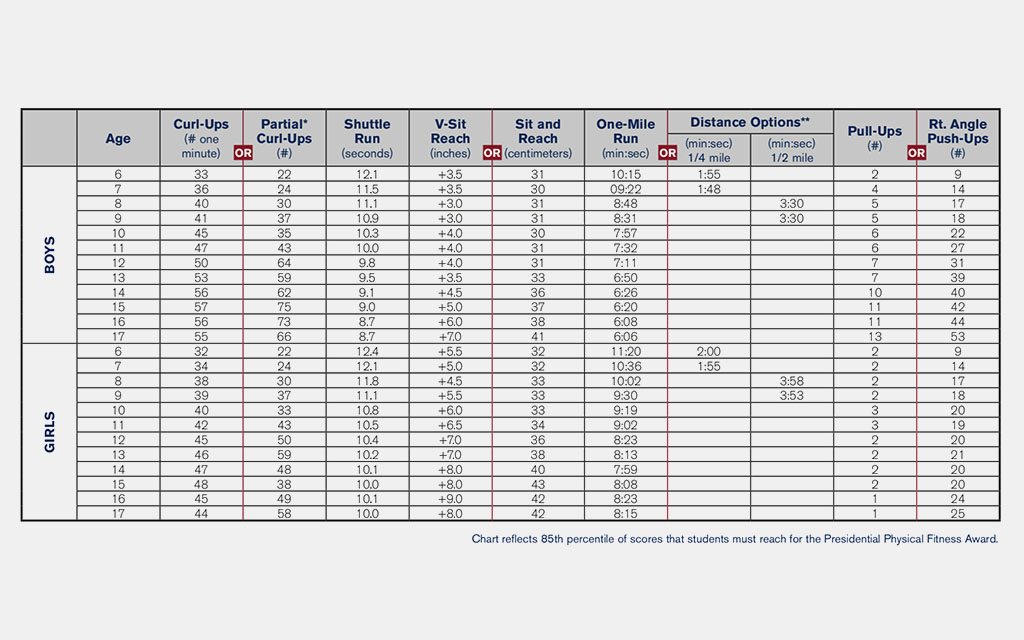

I struggled with this method. Very few trainers would recommend performing abdominal work for speed, and as I’m used to performing crunches — my feet cross in the air, hands laced behind my head — the action of slamming my back into the mat again and again came across as herky-jerky and uncomfortable. I tried my best nonetheless, and managed 40 in a minute, which was good for the 85th percentile (test-takers must reach 85% in all five events) for — here goes — an eight-year-old. I’ll go on the record here that America’s numbers are probably slightly inflated, as there’s only one adult present in class, but more importantly, I’m just not much to call home about on this exact exercise.

The Mile Run

I’m a lifelong runner. You can read about my time on the road in other editions of this column. One reason I was compelled to revisit the Presidential Fitness Test, despite memories of not being able to perform a single pull-up, was that I always excelled on my elementary school’s boxy, gravel “track,” where something like nine laps constituted a mile. Mile Run Day was the only occasion I ever had my mile timed growing up, and I always looked forward to seeing how many seconds I could knock off. To be sure, that day was definitely a living hell for other members of my class, so I won’t go ahead and credit the test for cementing a yearly, timed 1600 meters as a pre-pubescent rite of passage; I’ll just acknowledge it was a byproduct that I happened to appreciate. Anyway, I’ve been running lately and feel good. I ran a 5:14, which puts me well ahead of the 85th percentile for 17-year-olds (who ran a 6:06).

Pull-ups max

Redemption! I logged 11 pull-ups, which places me in the 85th percentile for 16-year-olds. (17-year-olds nabbed 13, apparently.) Similar to the curl-ups, the council was very precise on what “counted” during the pull-up test: horizontal bar, palms facing out (so no “chin-ups”), chin must clear the bar, body must return to the starting position, and they should be performed with a smooth cadence. No swinging. I remember lots of kids would do their best Shakira impersonation in an attempt to steal one more rep. That’s not kosher.

30-foot shuttle run

I don’t actually remember ever having to do this. It’s pretty simple, though, and a staple at summer football camps: Set up two cones on lines 30 feet away from each other. Put two small objects (blocks or tennis balls) on the opposing line. When your partner says go, sprint to the opposite line, grab an object, and bring it back, setting it down (no throwing!). Then go grab the other one, and head back, sprinting through the starting line. This is meant to test agility, and I actually think is one of the most functional assessments here — if not for time, at least as a way to judge one’s capacity for lateral movement, which is often locked up or adversely affected by improper mechanics, even for youngsters. Of course, we were timing. I managed an 8.87, which puts me just behind the 85th percentile of the 16-and-17-year-olds, at 8.7. Rats.

V-sit and reach

Assuming you don’t have a sit-and-reach box on hand at the house (if you do, email tips@insidehook.com, sounds like you’ve got a good story), pull out a measuring tape and sit on the ground with your legs spread out at a slight “V” angle. Stretch the measuring tape out a few feet and align your feet with the 24-inch mark on the tape. This is the base, the relative 0, for testing flexibility. Folding your hands one over the other, like a reverse Communion, push slowly forward and see how far (if at all) you can tap an inch mark past 0. I managed a measly +2, which did not qualify for the 85th percentile at any age available. Children are more flexible than adults — we lose elasticity in our connective tissue as we age, and we sit around all day staring at screens and trying to make sure we can pay for dinner — so I wasn’t particularly surprised. Even as a kid, I’d never come close to the gaudy numbers put up by some of the gymnasts in my class (the 85th percentile for 16-year-old girls is +8). Still, I took the result in stride, and resolved to focus more on stretching, on keeping my back healthy, on performing those basic movements that characterize a functioning, young(ish) body. In other words, the sort of movements Dr. Hans Kraus and Bonnie Pruden advocated for all those years ago — before their test became something else altogether.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.