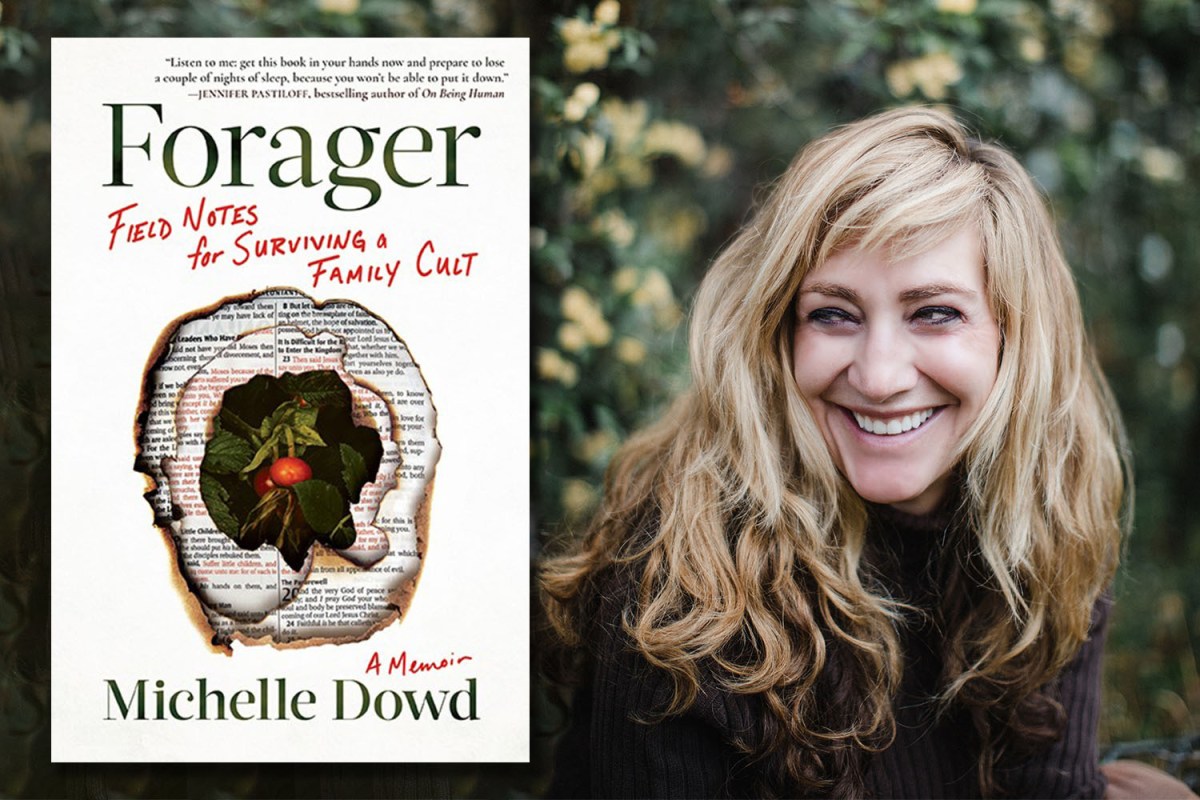

There’s a paradox at the heart of Michelle Dowd’s new memoir. Dowd grew up in California — specifically, in and around the Angeles National Forest. Her childhood was not a typical coming-of-age experience, however. Dowd’s grandfather was the founder of a cult known as the Field, which stressed isolation and a strict adherence to religious codes.

In Forager: Field Notes for Surviving a Family Cult, Dowd chronicles this experience, juxtaposing an at times harrowing account of her youth with memories of getting to know the region’s ecosystem through her mother’s interest in the area. Without saying too much more, these two elements eventually converge, showing how both played a role in the life of a nascent writer.

We spoke with Dowd about the process of writing her memoir, what her relationship with the outdoors is like and the unsettling ways that she’s reminded of the cult in which she grew up.

InsideHook: At the very end of Forager, you wrote about leaving the cult you’d been raised in and what your life was like after that. Was there one thing in particular that inspired you to write the book, or was it more of a gradual realization?

Michelle Dowd: It was not gradual. It was abrupt. I saw my brother this weekend and he asked, “what made you write this because we don’t talk about it very often?” He added, “I’ve been burying this my whole life.” He was introducing me to a bunch of people who are his family by choice. And he said, “This is my sister; she can tell you what our childhood was like because I don’t want to talk about it.” All of my siblings went in different directions, and the three of us who left didn’t talk about where we came from for decades.

I’d also stayed away from this story. Then in 2020, I wrote a Modern Love piece for The New York Times. I was doing it to demonstrate to my students that rejection is part of the process. So I did the piece and it got accepted and got put in like that week. It just moved so quickly. It made references to where I came from, and agents started calling me and saying, “I think there’s a story here.”

I signed with an agent and then wrote the book after it was sold. I think the reason I was ready to do it is because there was some violence that happened a few years ago. I had had a lot of violence in my adult life as well. So I finally went to therapy, both group therapy and individual therapy. I’d worked through a lot of it and I realized that I had not even told my closest friends where I came from. And so when I was given the opportunity, it just felt like I was coping right then.

The book is structured with different field notes about ways to survive in the wild. How did you arrive on this structure and decide to include all of these very evocative but also very practical facts?

I read quite a bit and I teach journalism. I’ve taught in prisons, and I’ve taught in colleges. And I always tell my students that you need to ground your piece in a sense of place. Because if you’re inviting a reader to come, they need to know where they are. So that is something that I’m accustomed to saying out loud.

My grandfather’s ideologies are so esoteric, I wanted to ground it in a place. And my mother actually worked as a guide — she didn’t call herself a docent, but I suppose that’s sort of what it was — at the Nature Center. They were also preparing us for the end of the world. The plants on our particular mountain were one of the things that we ate at the beginning. I felt that when I was thinking about the place, those plants were the most foundational part of what I consumed, and they also took me back to the actual geographic region. I went back up there and continued the research. My mother had done a coloring book for the Nature Center, and she included not all of these plants, but most of them. A lot of what I pulled out for the descriptions were my mother’s handwritten notes, even the notes that she wrote for the cards that ended up going on little placards.

I went on this trail, which I’d never done as a kid. The trail that shows these plants is still at the Nature Center. It’s kind of overgrown, but you can walk around and look at the plants and the pictures. They’re not identical to the ones I have in the book, but they’re on there. I felt like I could root the story in a place and then also show the ways that my mother’s ideologies were different from the ones that we were told from my grandfather.

That was one of the things that interested me most about the book: the way your mother had a life that seemed relatively separate from the cult. And you juxtaposed the ways in which you were isolated from the outside world, but certain other ways in which you interacted directly with it — taking part in a circus, for instance. Was that something that was unique or more commonplace than one might expect?

Both. Because my mother was the founder’s daughter, she had a degree of defiance. She would not have called it that, but she got away with doing things like having a secret life at the Nature Center that she could only do because she was the founder’s daughter. There’s nobody else that would have been allowed to do that. My father would not have been allowed to do that because he wasn’t blood. She got away with it. I’m not saying that she wasn’t secret, she absolutely was, but she had such a passion for teaching us about the land.

I think she wanted to learn and she wanted to connect to other people, like this entomologist. I didn’t use his real name, but he was a fairly renowned entomologist in the region and that’s how she taught us what bugs do. And so that was very specific to her being born and raised in the cult. But my grandfather and all the other people that he brought into the cult, those people were not allowed to have jobs and they had to give all their money to the organization. It was a small group, approximately a hundred in the inner circle.

A common thing in cults I’ve heard of are circles where you’re welcome to start learning, but then it’s only when you get into the real inside that your life is controlled. So at the very inside, you have to pledge service for life. I left before I turned 18, so I was trained to do it but I was also not quite at the place where they were marrying me off.

In terms of the wider context, it was a boy’s organization when my grandfather started it. There were a lot of boys who followed him from the 1930s who were old men when I was born. And they were still with him. They were all told how to live their whole life. By the time I was born, there were women in the organization, but it was still a men’s organization that had women as support systems. And so my mom maybe wasn’t held to the same standards as the men were.

Do you see any parallels between this cult and more recent phenomena like incels and the “manosphere”?

Absolutely. And that might even have prompted me on some level, too. There was the same incel attitude, there really was. It was like they didn’t like women, but they wanted them in order to have children. At this organization, there was always this sense of God making men for his ideal purpose, and then Adam being lonely and God letting him have a woman who caused the downfall of humankind.

Even the men who were allowed to marry were always taught not to trust women because we ate of the fruit. I tried to throw in a good portion of the attitudes about Jezebel. I don’t think Jezebel was the worst female character in the Bible. It’s just like, oh, we can name one.

Something else that I found very interesting in the memoir was that the organization you grew up in seemed to have a greater appreciation of Indigenous history than one might expect from the place and time.

Yes, I think because my grandfather came from Oklahoma and his legend was that he grew up around Indigenous people. I don’t know if that’s true — he lied about so many things. He was very pro-Native American ideology. My mother most certainly studied informally with a man who came from a long history — I’m trying to think, I wasn’t taught to think in terms of tribes. She worked with him and that was how she learned a lot about edible plants.

Because we were living on the mountain, that gave me the ability to question the whole hierarchy. On the mountain, it was more my mom’s territory than my dad’s. We didn’t have quite that same male hierarchy, so the men who were there weren’t there to reform and to get better, they were just living with us. They weren’t in charge.

Throughout the memoir, you wrote about your own development as a writer. There’s a part where you discuss hearing the word “pernicious” and zeroing in on the word outside of the context in which you heard it. Do you see a direct continuity between that and your work as a writer and a teacher, or was there more of a break between those two periods?

There’s a direct continuity. I wrote about getting the Sears catalog, and I also have a Bible from that time that I marked up. I was in love with language by the time I was 10. When I went to the hospital, I was looking for language. I have hundreds of pages of notes that I tied together with strings from the ages of 12, 13, 14, 15 and 16. The boy who’s in the book is always checking on me — he has checked in with me a couple of times a year since forever, he’s never lost touch. And he always says, “You always wrote everything down. Everything I said, you would write down, you would just sit there and write stuff down.”

To put it in context, after I had all these children and I went straight to grad school, I was teaching college as a TA but I was also in the university writing program. By the time I was 22 at the University of Colorado, I was teaching full-on freshman writing classes. By the time I was 25, I had written a whole book and I had a publisher interested. They wanted to publish it as nonfiction. I wanted to publish it as a novel. And so I was really scared and I even put it away. And that’s like the last time I wrote for a really long time.

I excerpted direct passages from that book, which was called The Layaway, and put it in here. So some of the passages of the book were written before I was 25. When I would do a memory scene or something, I had an old file I could refer to. I think that I was ashamed to use the word “cult.” I was ashamed to talk about my family because it was very, very forbidding. My brother said, “I cannot believe you’re doing this. You know, I’m still thinking you’re gonna be struck by lightning and you’re going to be dead so they kind of come back.” I said, “Thank you!” (laughs) But yeah, I get it. He’s said, “I’m super scared for you.”

During this time, I had another piece published in The New York Times. It’s not that I think I was incapable of writing, I just think that I didn’t want to talk about it.

Journalist Andy Greenberg on His New Book “Tracers In the Dark,” Crypto Crime and the Fall of FTX

“Tracers in the Dark: The Global Hunt for the Crime Lords of Cryptocurrency” is out nowWhat is your relationship to the outdoors now? Do you still spend time there or is it associated with bad times in your life to the point where it’s something that you avoid?

I find it incredibly healing. So during COVID, I got 10 acres in the mountains. I’m still alone out there, really, but I have been hiking. I went to college in Boulder, Colorado and hiked every day. I didn’t have a car. I had babies on my front, my back, everywhere. Since I’ve been back in California, there’s a mountain called Mount Baldy really close to us. I don’t think I’ve gone more than a week without hiking in the mountains. It’s a huge part of my life.

Do you still make use of the outdoor knowledge you include in this book, like getting pine nuts out of pine cones or boiling acorns?

Yes, I do. For example, I boiled 100 elderberries this last season. There was just a huge crop. I like to leave some for the birds and the bears and things that are up in the mountain that I go to. But I make the elderberries into tinctures and all that like every year, for sure. I make rosehip tea from my yard. I don’t subsist on them, but when I go backpacking, I would use them as actual sustenance.

Is there anything else you hope people will take from Forager?

I wrote, near the end of the book, “A fit organism won’t stop at survival. It attaches to what it needs to grow and thrive.” And when I think about my life, I think I did struggle with a lot of things. But once you get past basic survival, any organism, whether it’s a plant or a human, is going to find a way to interconnect to get what it needs. And I think that one of the themes I wanted to come across in the book is that you can find what you need — you just have to know what you’re looking for.

So many of us don’t know what we’re looking for. And I think that is what sometimes goes sideways. And I truly think that there are a lot of answers in the natural world that most people have not had a chance or the time to observe. I think it’s a privilege. I feel that I was very grateful for the time I got to spend living on the Earth like that.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.