If you weren’t thinking about the way that everyday objects were designed before this year, 2020 has provided plenty of opportunities to do so. Weeks or months of self-isolation offers a lot of time to think about the way your home is designed for its inhabitants; concerns over COVID-19 can, in turn, prompt thoughts about the surfaces we touch, whether of furniture or gadgetry.

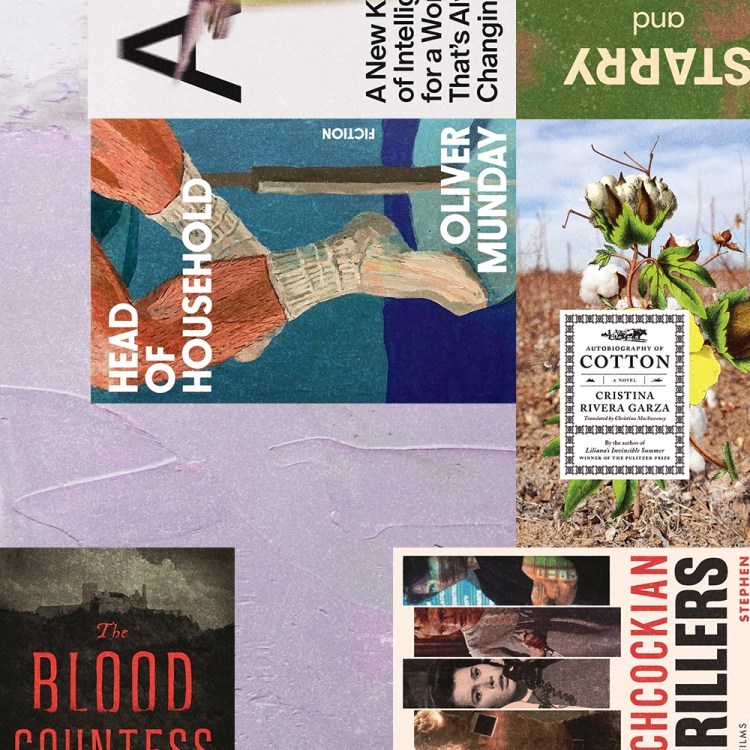

Maybe you’ve been prompted to radically rethink elements of your living space or have found a new curiosity surrounding how certain objects evolved into their current form. A trio of recent books offers a glimpse into how the spaces and objects around us influence us — and, with the onset of COVID-19, their authors have been thinking about the ways in which the pandemic has accentuated their areas of focus.

“A big lesson of minimalism is that you can pay attention to anything. Everything around you is worthy of artistic consideration, whether it’s street noise or a metal box.” So says Kyle Chayka, author of The Longing for Less: Living With Minimalism. “So while being stuck at home in quarantine,” Chayka says, “it at least makes it more interesting to reconsider the stuff in my apartment.”

The Longing for Less is a concise yet wide-ranging book: Chayka explores minimalism in a number of permutations, from home design to contemporary music. It’s the rare book with a focus that can take in both legendary designers Charles and Ray Eames and cult composer Julius Eastman. And, for Chayka, that overlap of disciplines proved to be his favorite element of working on the book.

“My favorite design elements were writing about the home interiors of people like Donald Judd, the Eameses, and Philip Johnson, how their homes reflected their artistic identities and ideas,” Chayka tells InsideHook.

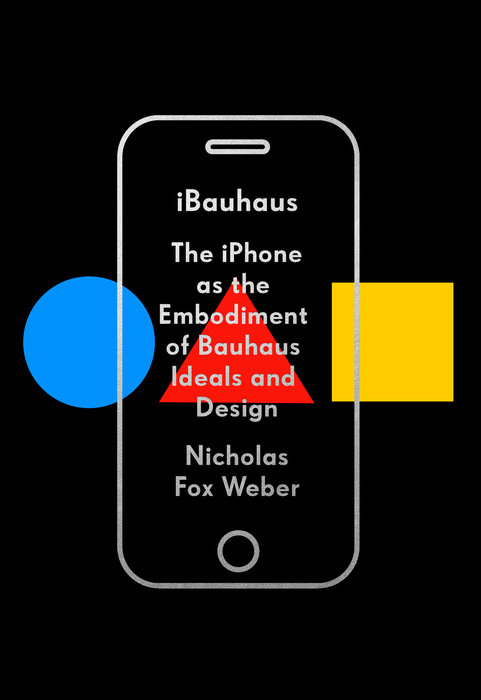

That sense of unlikely connections between objects and aesthetics is also at the forefront of Nicholas Fox Weber’s iBauhaus: The iPhone as the Embodiment of Bauhaus Ideals and Design. Weber’s knowledge of all things Bauhaus — the Weimar-era art school that shaped an abundance of thinking on art and design — comes via his work running the Josef and Anni Albers Foundation. And his thesis in IBauhaus is a concise one: “that the iPhone is the ultimate embodiment of the Bauhaus goal of good design applied to mass production,” as Weber writes.

For Weber, the book’s premise came via a hunch that “the iPhone is something that people at the Bauhaus would have loved,” which his subsequent research proved to be accurate. “I only discovered after having the feeling that this was so that Steve Jobs was a Bauhaus junkie, and that Jony Ive was trained in true Bauhaus tradition,” Weber says. “So the roots were where I instinctively felt they might be — but to a far greater extent than I imagined.”

Throughout his book, Weber finds unexpected connections between Bauhaus thinking and the development of the iPhone. He notes that the iPhone blends simplicity and innovation — and, like a lot of work that emerged from the Bauhaus, its impact was seismic. It’s not difficult, after all, to apply the iPhone’s reinvention of what a phone can be to the broader category of smartphones as a whole — of something that’s taught people how to use them anew.

Design’s capacity for teaching us how to use things is, on a larger scale, the focus of Alexandra Lange’s The Design of Childhood: How the Material World Shapes Independent Kids. Lange uses this concept to explore the design of countless objects and spaces a child might encounter, from toys to schools to cities.

“There’s a famous saying by the architect Ernesto Nathan Rogers that he wanted to design everything ‘from the spoon to the city’ — it sounds better in Italian, ‘dal cucchiaio alla citta’ — and the idea that the designer could and should work at scales from the personal to the world-building is very much part of the history of modern design,” Lange says.

The history she covers in The Design of Childhood is a fascinating one, which includes mid-20th century school design in the United States along with considerations of how some enterprising thinkers have used 3D printing to develop connectors between different sets of toy systems. That would be the cheekily-named Free Universal Construction Kit — which Lange calls “one of my favorite objects ever, both for its usefulness and for the clever way it gets around the intellectual property fencing that is part and parcel of the toy industry.”

For Lange, the growth of open-source movements and the collaboration that accompanies them plays a significant role in shaping kid-centric design. “The future of play for kids already relies more on customizable and open-source things, particularly in digital playgrounds like Fortnite (to a limited extent, as with the skins economy) and Minecraft (with more freedom) or even with hybrids like Nintendo Labo,” she says. “We will see (and do see) many more kids making both IRL and digital prototypes, creative messing around, shared and played within friend groups.”

Those questions of parenting and play also feed directly into Lange’s discussion of life under quarantine. “All those kids at home— what are they playing with? Which toys are occupying them for the longest? What games are they playing with their friends online?” she asks. “I bet it is classics like blocks and Magna-Tiles. I’ve gotten several anecdotal reports of fun with cardboard boxes, and my kids, who are older, have gone back to Minecraft.”

Just as Lange deals with indoor and outdoor spaces and objects in her book, so too does she bring up both in the context of the current pandemic. “Meanwhile, outside the home, the playgrounds have been shut down, but lots of families are exploring their cities in new ways since the best way to get outside is to walk,” she says. “I know people are going on Instagram scavenger hunts. People are finding out everything they can reach in a half an hour on foot or by bike.”

For Lange, changes in public health policy today may have an impact on people’s behavior even after a vaccine has been found. “Some cities are giving over more space to pedestrians and setting aside more bike lanes,” she says. “That is going to change the post-coronavirus expectations, of parents and kids, about where they can go. ”

For Weber, the current pandemic raises questions of touch — which in turn hearken back to some of the issues he raises in IBauhaus. “I have just been reading lectures that Josdef Albers gave in Havana in 1934, and he emphasizes the tactile beautifully — the difference between something soft and wooly — let’s say in a bright red —and something totally smooth, in the same red. We see the color differently; we feel everything differently,” he says.

He notes that the present crisis might accentuate that even further. “People will want, now more than ever, to feel that something is sanitary and clean,” he says. “At the same time, it is said that the virus spreads more easily from smooth surfaces than, say, cardboard. So people will be all the more conscious of the tactile.”

But even if you’re not out and about, careful consideration of the objects around you can still be revealing. For Chayka, staying closer to home during quarantine has accentuated his perspective on minimalism. “A big lesson of minimalism is that you can pay attention to anything. Everything around you is worthy of artistic consideration, whether it’s street noise or a metal box,” he says. “So while being stuck at home in quarantine, it at least makes it more interesting to reconsider the stuff in my apartment.”

Recent months have also left him with the sense that minimalism might be ripe for a comeback, if it ever left. “I think minimalism’s linking of simplicity with coolness and elegance will be very relevant once the inevitable recession hits and we once again have to readjust our expectations for our economic lives,” he says. “Unfortunately. ”

The design history that Chayka, Weber and Lange explore in their respective books is wide-ranging, and covers decades of thought and process. Even at a moment in time punctuated by a global crisis, the ways of thinking and methods of perception that they cover have a lot to tell us about life right now — and what life a year or two from now might be.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.