Pop culture was forever changed on October 5, 1962 — twice over. That was the date on which The Beatles’ first single, “Love Me Do,” hit record stores in the U.K. It was also the date on which the first James Bond film, Dr. No, began its theatrical run.

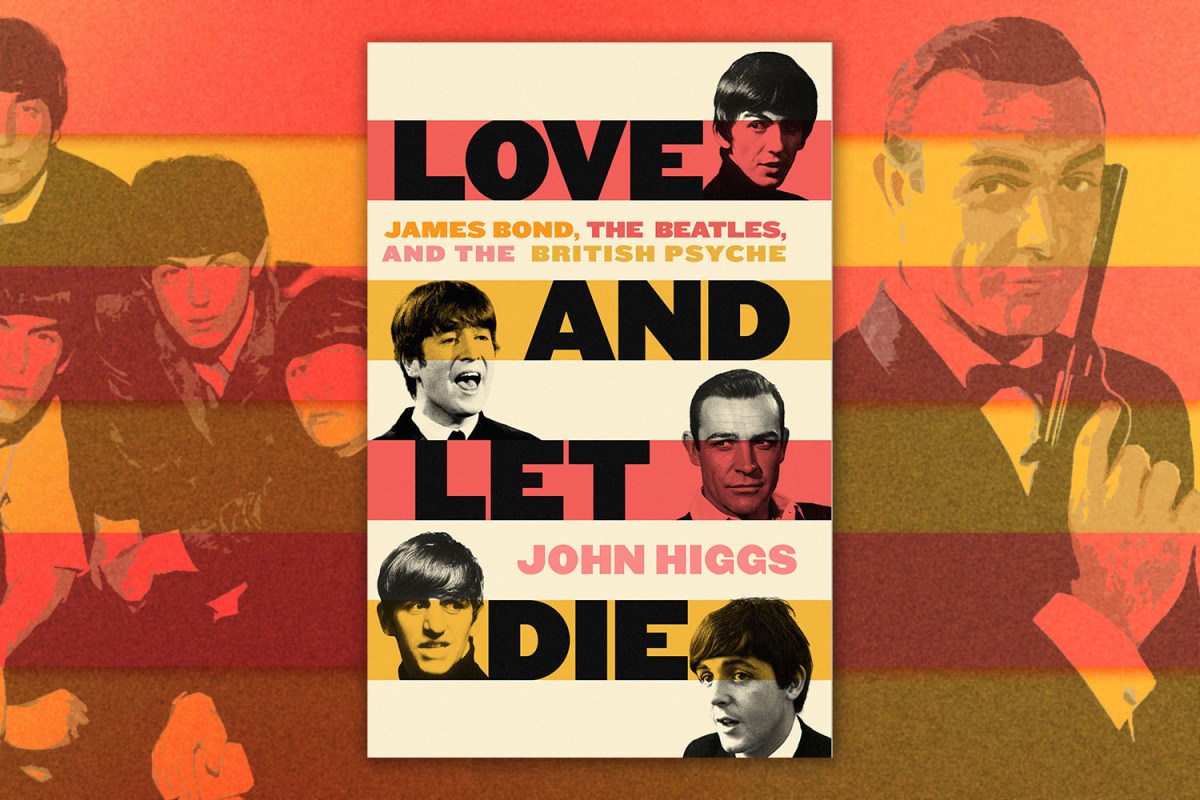

It’s out of that unlikely convergence that John Higgs began working on his new book, Love and Let Die: James Bond, the Beatles, and the British Psyche. Higgs has written about subjects as varied as Timothy Leary, William Blake and the concept of monarchy — and his breadth of knowledge suits the limitless permutations of his subjects well.

For Higgs, both James Bond and The Beatles provide a way to examine questions of masculinity and class — along with how audiences’ perceptions of both have changed in the decades since that fateful day in 1962. We spoke with Higgs about the genesis of his book, Ian Fleming’s writing routines, and the ubiquitous nature of Christopher Lee.

InsideHook: When did the idea first come to you to look at the areas in which — culturally speaking and biographically speaking — the Beatles and James Bond dovetailed in unexpected ways?

John Higgs: It was more the moment that I realized that the first Bond film and the first Beatles seven inch came out on the same day. It was one of those days when you just got a bit distracted and you’ve gone down a Wikipedia hole and you find yourself on the Wikipedia page of Dr. No. We’ve all been there, surely. And I just saw that the release date was the fifth of October, 1962.

I’m enough of a Beatles nerd to think, “No, that can’t be right. Surely that can’t be right.” I checked. Once I saw that it was true that the first Bond film and the first Beatles single, came out on the same afternoon, something about putting the two of them together just started to reveal so much about each other. They’re both so familiar, but the moment you bring them towards each other it’s like a dialogue. All these views on masculinity or class or you know culture in general just started blowing out of them.

I was very interested in how you used both to talk about masculinity. You have the individual masculinity of the members of the Beatles, but also James Bond — both as written by Ian Fleming and portrayed on film — and Ian Fleming himself. How did you deal with that in both the collective and individual senses?

I think it was more a case of how they differed and how they clashed. When young men were growing up after the Second World War, growing up on war comics, there was a sense of masculinity where you had to be brave and strong and good at fighting, and that was what made you a man. And then came that weird realization that that really wasn’t what the girls wanted at all — they were screaming at these somewhat feminine-looking hairy guys who were singing openly about emotions.

For a lot of boys and men, suddenly there were options. There were choices to be made — did you want to be the brave, strong, good at fighting, emotionally closed off type of man, or was what the Beatles were offering more fun? It seemed like there was a better life than that way.

In a lot of cases, that idea of masculinity also relates to class — whether it was the working-class origins of the Beatles or Fleming’s more aristocratic background. And then that gets complicated as well, as the members of the Beatles became wealthy and Sean Connery, who had a working-class background, became the definitive cinematic Bond.

It’s one of those things you’d rather slightly tiptoe around, but when you have a story like this, you can’t just ignore it. In the book, I mentioned something that the writer Hanif Kureshi wrote about — how when he was growing up in school, he was taught that the Beatles were a hoax. His teacher told him that there was no way that those four lads from Liverpool weren’t from the right families, they didn’t go to the right schools; there was no way they could be making music that was self-evidently better than all the right people.

Hanif Kureshi really perceptively noted that he understood that his music teacher had to believe that conspiracy theory because otherwise it would take too much else away. It went right to the heart of his, sense of identity and his worldview, his belief system. That, in particular, highlights to me just what a blow to the English class system the brilliance of the Beatles was. It was something that I don’t think has ever been the same since, to be honest.

After the Beatles, you get things like Monty Python constantly mocking the upper class, with “The Upper-Class Twit of the Year,” where it’s just a joke. So yeah, the Beatles are responsible for a lot of change. I do think that is an important one.

I’m not sure if you’ve been following the “nepo baby” discourse, but it seems interesting how that intersects with the idea of an upper class producing artists. And I’m curious — do you think there’s space for an artist coming from a similar background as the Beatles having success on the same scale in 2023?

It’s definitely swung back the other way. The playing field is very much tilted against the people without family money again. The Beatles were the stars of the period, in the same way that punk and then heavy metal and hip-hop and all these working-class cultures wanted to challenge the way the world was and wanted a better world. When the music is made by people for whom the status quo works quite well, it doesn’t have that fire, it doesn’t have that need to change things.

That has a lot to do with the cost of housing and the impossibility of living in a place like London without money behind you when you’re starting out and trying to be a band. And it explains why there’s been a move away from bands towards someone in their bedroom. There’s still great stuff being made, but it is definitely noticeable, the extent to which when someone does well in the music or film industry, you go to their Wikipedia page and you see that their parents’ names and their school are all hyperlinked.

To shift directions a little, how did you decide what to include and not include in the book? In terms of James Bond, for instance, you covered Ian Fleming’s books and many of the films, but not things like, say, the Bond novel Kingsley Amis wrote after Fleming’s death.

With the book, I had to have my own parameters and decide if I was going too far. I decided to just stick to to the main characters, just Fleming and the character of James Bond and how he evolved on screen. How he changed in the books was less interesting to me, I think, because it was more faithful to the novels and things like that, whereas the Bond on screen, which is the Bond that most of the culture knows, was changing a lot more as men were changing.

I mean, if I didn’t have a deadline, I could still be writing it. The Beatles alone are infinite. You never run out of things to say about the Beatles. And once you’ve got something like Bond and the Beatles, those huge cultural touchstones, it was a case of selecting what I could say that hasn’t really been said about them.

What We Learned From Watching “The Beatles: Get Back”

The biggest revelations from Peter Jackson’s nearly eight-hour docThere’s an interesting comparison between Ian Fleming having a very set routine when it came to writing his novels and the members of The Beatles constantly trying to outdo what they’d done before. Did you see that as a kind of conflict, or as a case of the two artists being more similar than anything else?

I would say that there was more similarity than not. The thing with all great artists is they put the work in. They do what needs to be done. They turn up regularly. They get their guitars or they get their typewriters and every day they turn up and they work. And I can’t really see how this story would have happened if that hadn’t been the case. Fleming didn’t work like that and if Paul and John and George and Ringo also didn’t work that way. It’s there in every great story of where culture was changed by imagination and art.

In Love and Let Die, you cover a handful of figures who were in both the Beatles and Bond worlds — especially Christopher Lee. Did you find that any of the people who overlapped in the Beatles world and the Bond world had anything in common?

Nothing other than a remarkable ability to have been the right place at the right time — to be at the really exciting edge of things. Christopher Lee’s life was just extraordinary when you look at how he lived and everything that happened to him. It would be amazing if he didn’t meet people like the Beatles and James Bond at the same time.

Certainly, once you get to the 1970s, the individual Beatles are very much accepted parts of the celebrity system. You read so many accounts in memoirs — like when Ringo and Maureen [Starkey Tigrett] split up they had just gotten back from Roger Moore’s house; things like that. Whether it was anything that unites those people, I’m not entirely sure.

One of the things you bring up in Love and Let Die is the fact that the first onscreen adaptation of James Bond re-imagined him as an American secret agent. And there’s also an argument to be made that the most successful band to arise as a way to cash in on the Beatles were the Monkees, who could feel like an American answer to the Beatles. What do you think it is about both the Beatles and James Bond that feels very British — but also led to Americans try to come up with their own versions of them?

On one hand, I look at the Beatles and Bond and it seems to be post-war Britain having an argument with itself about how it can be modern, how it can be a new sort of what it means to be British in the post-war era. And it can seem a quite peculiar sort of thing, except for the fact that America and the rest of the world were also on board. They were also fascinated by the Beatles and James Bond and they were massive global phenomenons, which sort of says that they do transcend Britain

It’s quite funny if you’re in Britain, because the way the country seems to be seen from elsewhere, there’s very little relationship to the country that we all know and we all live it. Things like Downton Abbey are utterly alien to us. There is a sense that we’re still living like that and it is kind of odd. I mean, that sort of subculture, it still exists in places, but it’s not many people, and it’s not distinctive or anything like that. In the same way that I wouldn’t expect you to be able to lasso a steer or some other cowboy kinds of thing as a modern-day American.

It is interesting that the most popular cable show in the U.S. right now is Yellowstone, though, which does tap into that somewhat.

Yeah, it’s still a thing. Don’t get me wrong. It does exist, but it’s not typical and it’s odd to be defined by a strange little subculture like that.

You didn’t write too much about personal favorites in Love and Let Die. Do you have any favorites from the Beatles discography and the Bond series?

Absolutely. I mean, I love The White Album. I’ve got a huge love for Goldeneye. It’s my favorite, but my book’s not so much about, “Hey, I like Golden Eye.” It’s more trying to find new perspectives and new context on things that aren’t very very familiar to us — new ways to look at them that help reveal just how interesting they are, see them in a new light and make them even more compelling and more curious and more interesting, that’s really what the aim is. But I’ll defend The White Album over anything.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.