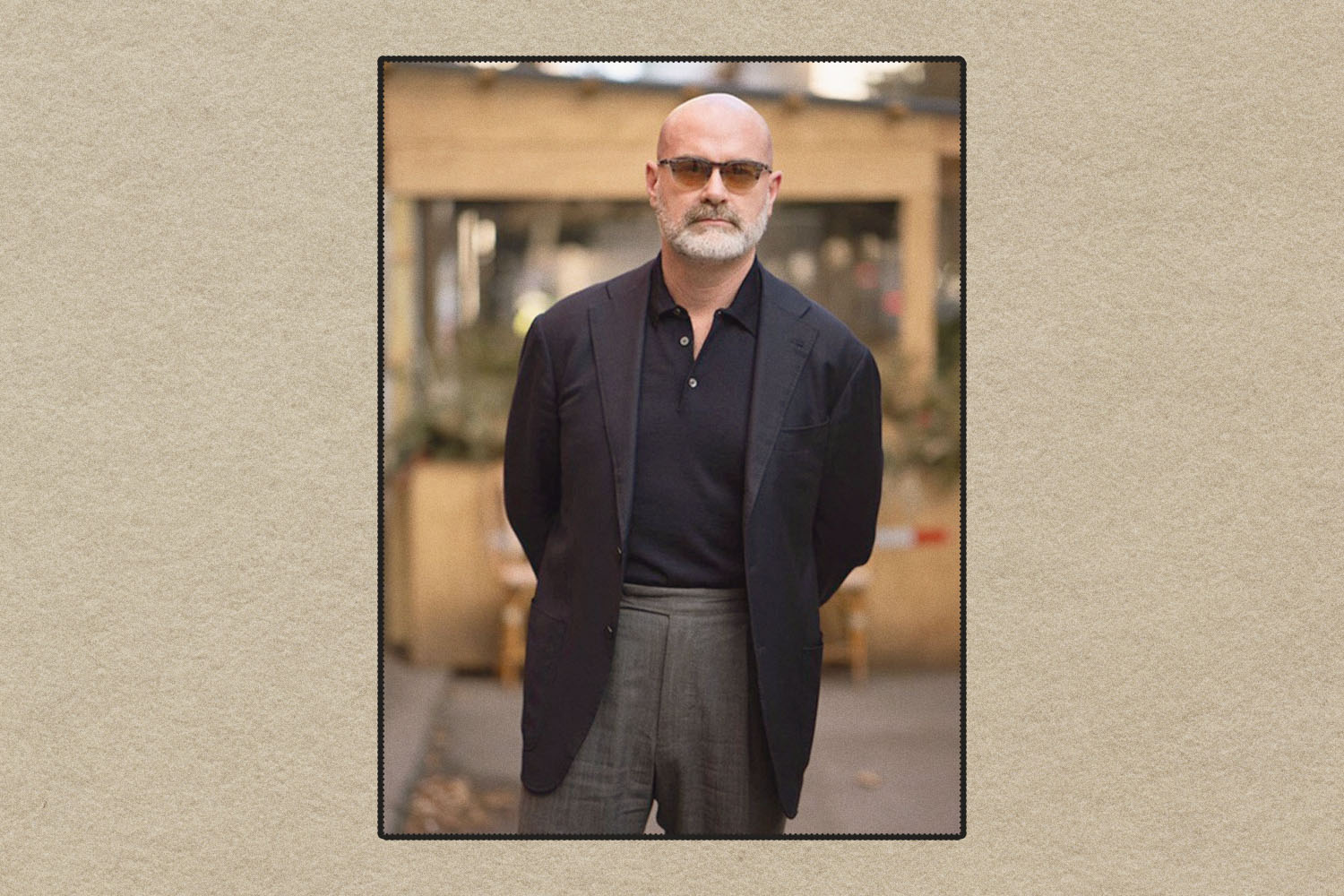

During my first post-pandemic visit to New York this past Spring, I visited The Armoury Westbury, a tightly curated men’s shop on the Upper East Side, to reconnect with tailoring. Its manager, Dan Quigley, was well-attired in grey wool trousers, a navy polo shirt, and a navy sport coat.

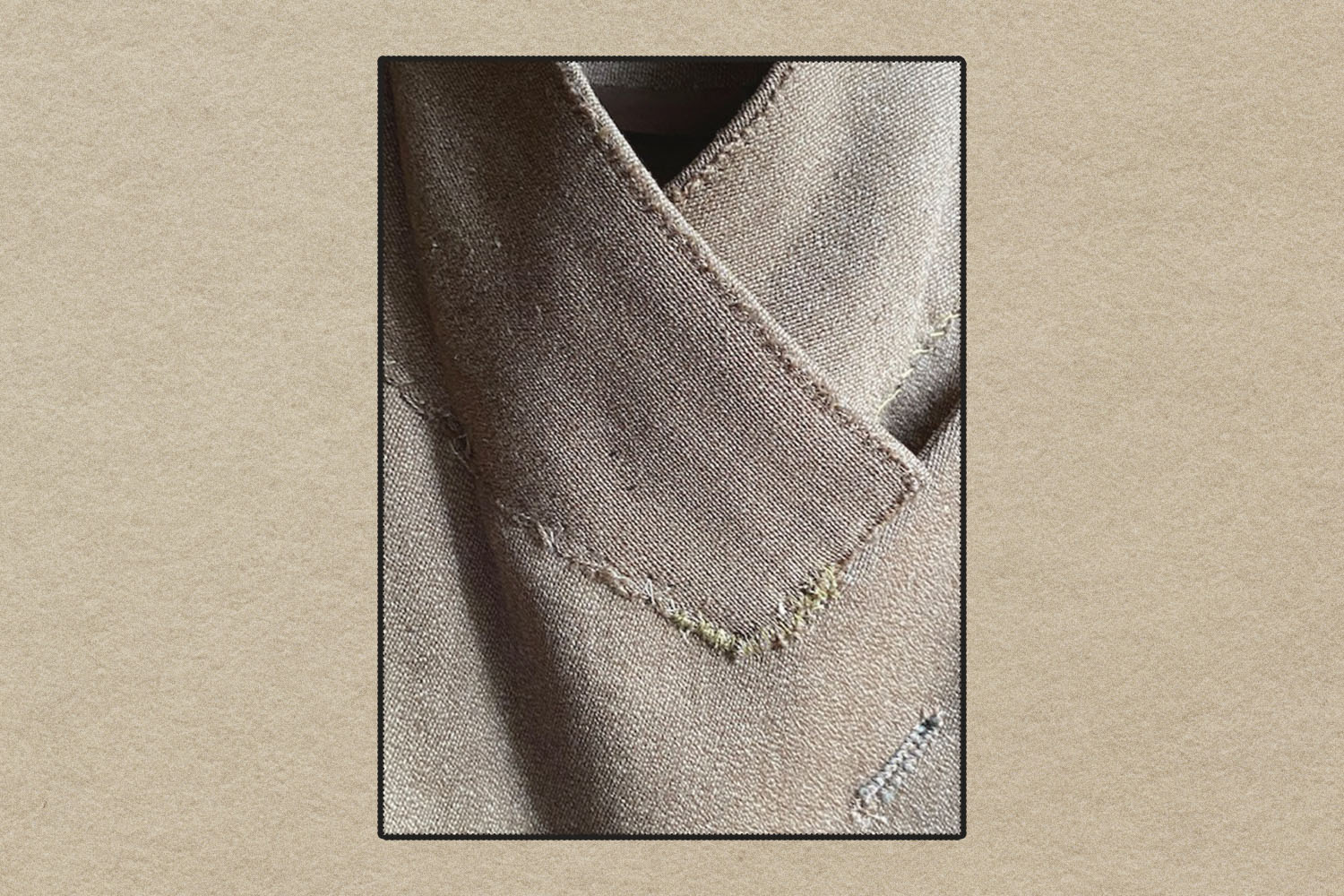

I admired the ensemble, which Quigley had finished with an indigo neckerchief, and noticed on closer inspection that the coat had seen some serious wear. Its patch pockets were pulled out of shape from hosting his hands, a hole at the elbow had been patched up with visible stitching, and smalls frays or stains appeared elsewhere on the arms and chest.

The coat, in a word, was beat. It had suffered indignities that would have seen it exiled to the far-corners of my own closet. But Quigley was wearing it on the clock and looked great doing so.

The difference, of course, was attitude. Whereas every mark or scuff on my own tailored clothing could mean the end of a garment’s lifespan, Quigley wore his with the same confidence as he would a new commission. In that moment, I knew I had to make a mental change and stop being so damned precious about my own kit.

After all, why shouldn’t we celebrate a blue blazer’s battle scars? Since the original #menswear boom of the late aughts, every fade in a pair of selvedge jeans or patch on a Barbour jacket has been viewed as a feature, not a bug. Adopting some of those same views around signs of wear could help ensure that tailoring serves as a long-term investment and be properly enjoyed.

With this in mind, I decided to ask a number of shopkeepers, writers, and other menswear figures how they felt about wear-and-tear. I started with Quigley, who explained that his coat’s elbow rip occurred after it was snagged by a table at his favorite restaurant.

“Let’s just say I wore it in with love and memories,” he says of the wool hopsack sport coat, which was made by Ring Jacket for The Armoury in their Model 3 configuration. “These beautiful imperfections are what make it uniquely mine.”

Men and Style author David Coggins seems to agree, citing the example of a Kiton overcoat he’d purchased years ago from Bergdorf Goodman, which has since had its lining replaced, been darned in several places, and generally frayed. “It’s got a lot of personality,” he says. “I love this jacket. It’s not perfect, but that’s alright, neither am I.”

True Style author Bruce Boyer remarks that he’s worn a double-breasted covert cloth overcoat made by the now-defunct Garrick Anderson label for close to 30 years, and in that time resewn its lining, repaired its pockets, and re-stitched the undercollar himself.

“If you turned that collar up, it would look like a surgeon did a bad job on a heart transplant,” he says. “I don’t do the neatest stitches, but I do the strongest.”

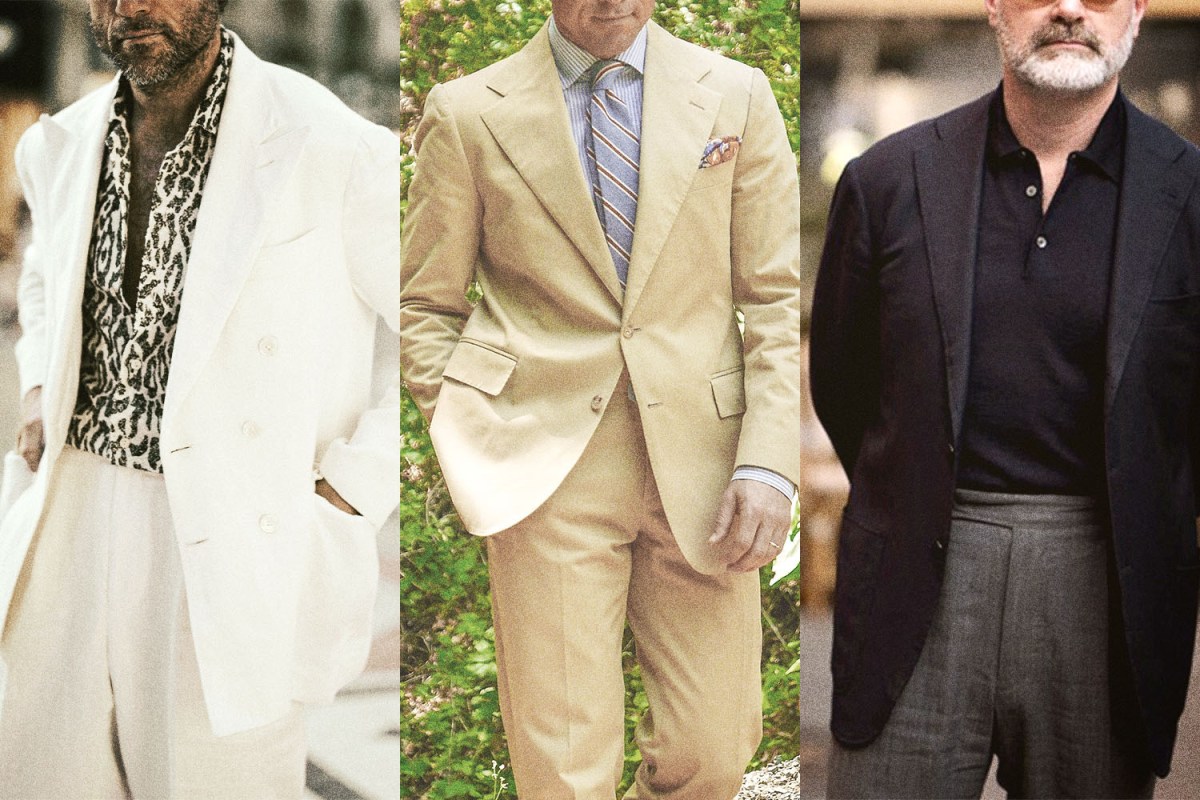

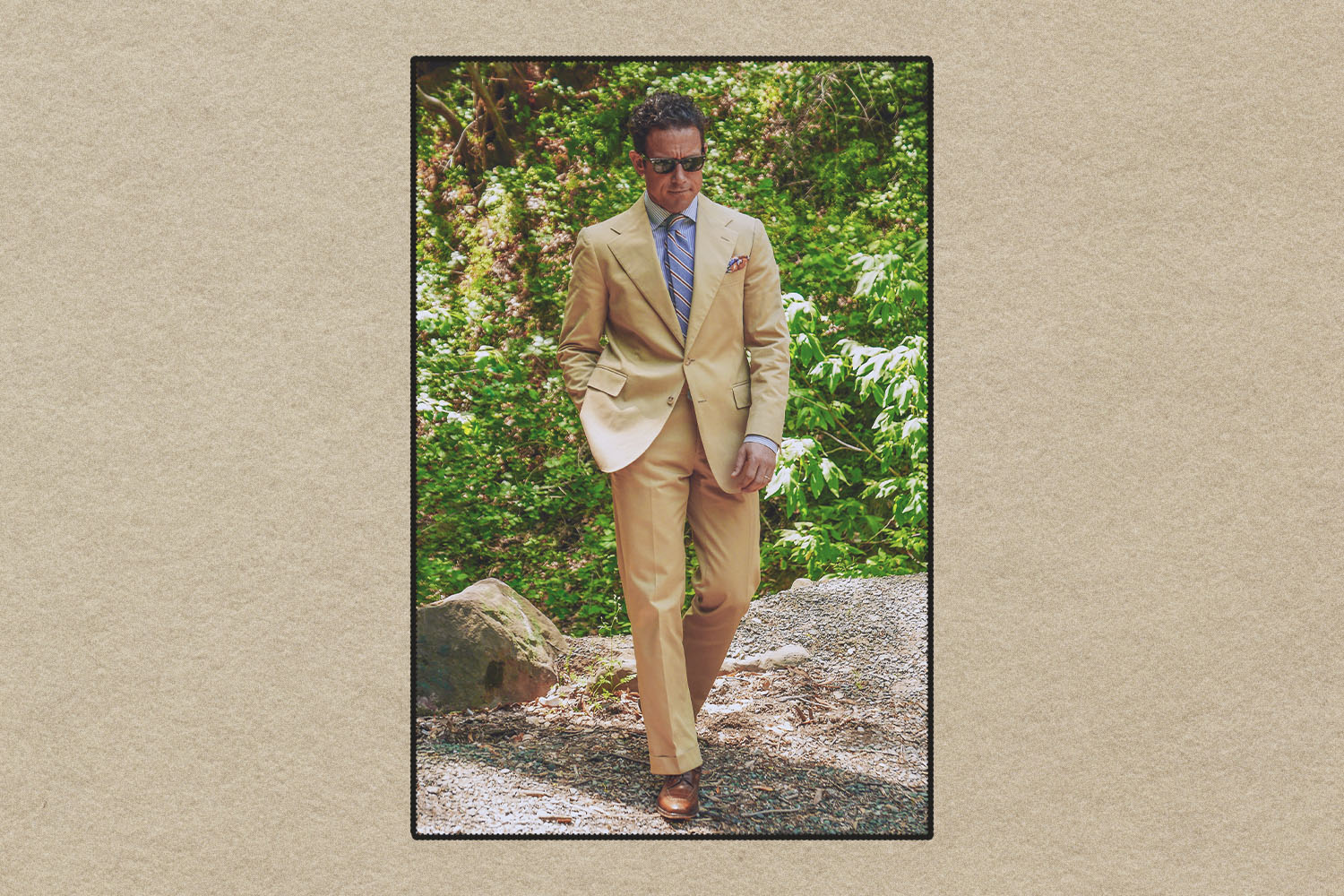

Peter Zottolo, who serves as the U.S. Director of Plaza Uomo and posts to Instagram as @urbancomposition, has a few war stories. Around 10 years ago he spilled a green vegetable smoothie on a tan cotton Polo Ralph Lauren suit during its first wear.

“I was horrified,” Zottolo says, adding that his first thought was to toss it. “After the initial shock wore off, I just couldn’t throw it away. I thought I’ll just wear it; I doubt that anyone will notice it. And sure enough, no one noticed it, not even my wife who sees me in it all the time.”

Not one to swear-off light-colored tailoring, Zottolo later had a double-breasted white linen suit made by bespoke tailor I Sarti Italiani, which he debuted at Harry’s Bar in Florence during Pitti Uomo.

“As I left, there were multiple Negroni stains on the jacket and I thought, you know what, I knew what I was doing. All of these are memories of the evening and I’m just going to live with it,” he says, adding that he continues to wear the suit five years later.

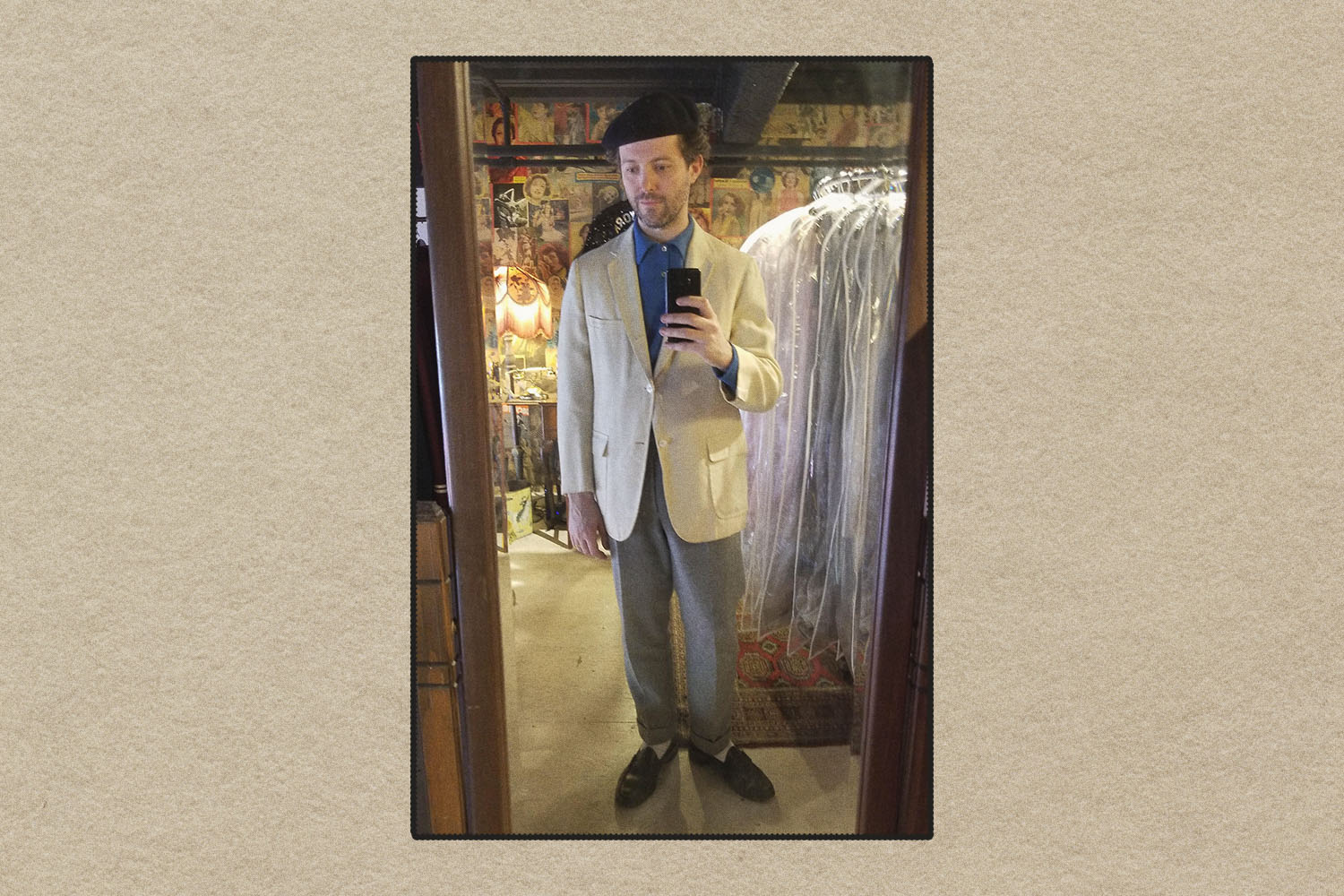

Dick Carroll, a Brooklyn-based freelance cartoonist, is unfazed by wear and tear. “Stains never bothered me that much, but I’m not really interested in tailoring for that pristine, clean aspect of it anyway,” he says, adding that he’s more inspired by the “romantic ideal” of artists who wore suits by choice, not necessity.

He recalls a cream silk Ring Jacket from The Armoury that he’s since given to a friend but had frayed to the point that its inner canvassing was visible at the cuffs, placket and inside collar. He presently owns another cream sport coat from shuttered Hollywood trad brand Carroll & Co., which was thrifted in an advanced state of wear.

“It’s toast, man. I feel like every time I wear it, it might just explode,” he says. “There’s no chance of repairing this thing, but it’s so fun to wear.”

Sid Mashburn of the same-named label has an appreciation for another, more subtle, sign of wear: fading. He cites one of his brand’s signatures, their leno-weave hopsack jacket, whose color has a tendency to move when exposed to daytime light.

“There are guys, me included, who have had the navy version for some 10 years, and it’s faded to a slightly softer blue with a hint of red afterglow,” Mashburn says. “It’s very cool and a kind of badge of honor. For me, time has been kind to this fabric.”

Time can be kind — or unkind — to the tailored clothing that classic menswear types exert so much mental energy and hard currency over. But those that rush to replace something at the first sign of depreciation may run the risk of never truly owning anything at all.

“I am a big believer in committing to clothes,” says David Coggins. “Only when clothes are really worn in do they become yours.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.