A gentleman we’ll call “James” recently went from a daily drinking habit that demanded five or six drinks to one that saw him consume around 12 or 13 per day. The stress of the pandemic was likely a motivating factor for the uptick, says the 40-year-old South Jersey resident.

With a family and a career to consider, he decided to check into a detoxification center where he facetiously says “the funniest thing ever” occurred. During a group discussion, another male attendee asked James how much he drank each day. When James told him the tally, the man roasted him.

“What the fuck are you here for?” he asked James. “I was drinking six or seven pints of straight vodka every day!”

“It was a joke,” James explains, but that incident helped push him right off the wagon. “I remember coming home thinking, ‘I’m not as bad as these guys.’”

Those guys’ proverbial rock bottoms arrived when they struck their spouses, lost their jobs, got DUIs or even killed others in drunk driving accidents. James never did any of that. “You can still drink,” he told himself. “You’re fine.”

James was not fine, though, and on a deeper level he knew it. He sensed he had to stop drinking, even when he’d say to colleagues and friends, “I’m a high-functioning alcoholic,” and they’d laugh it off. He still wanted to quit, even when sizable paychecks from his management job kept streaming into his bank account, seemingly indicating that he didn’t — couldn’t — have “a drinking problem.”

“Sometimes you just have to wave the white flag,” he says.

Two and a half months ago, he enrolled in another intensive outpatient program at a detox center, where he remains. He’s confident that this time sobriety will stick.

James’s road to recovery zigged and zagged, stopped and started like many before him. But he believes a more direct route could have been taken if his alcoholism was more extreme, perhaps on the level of the other men he met in rehab. If he’d, say, broken his back in a single-car accident while driving under the influence, or lost his home because he spent too much money on alcohol, perhaps he might have checked into a facility sooner.

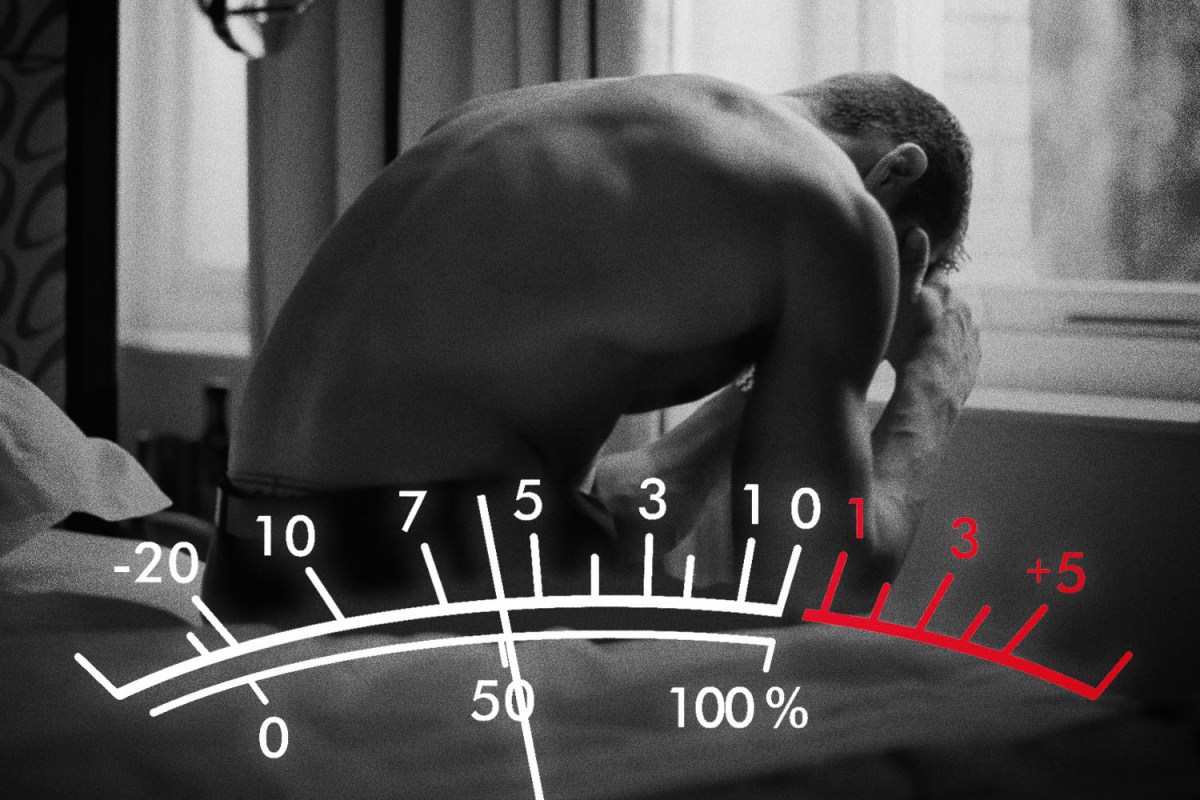

Such is life for many like him. These “tweeners” fall somewhere in the middle of the spectrum of addiction, making their substance problems trickier to manage — if they’re even noticed at all.

“You don’t have to be a homeless person struggling on the street to feel like you want to get a hold of your substance issue,” says Rachel Schwartz, a therapist and addiction counselor based in Brooklyn. In her mind, there are myriad reasons for why people abuse various substances, and why they want to stop.

Some individuals have drug problems so severe that they spur some bodily dysfunction, for example, prompting a physician, friends or family to intervene and ship them off to a treatment center. We’re familiar with people who struggle in such ways, from within our actual lives, but also because addicts of that caliber are depicted so regularly in media as well.

But as Schwartz notes, there are also people who feel “psychologically addicted” to a substance and want to make a change, people who are simply tired of thinking they have to have that glass of wine at five o’clock every night.

“You just don’t want to feel like it’s running your life in that way,” she says, where “you’re using it as a coping mechanism, and you don’t feel like you want to be relying on it.”

Danielle Tcholakian, a 34-year-old freelance writer living in Western New York, can certainly relate. She’s lived with anxiety and depression most of her life, but began experiencing a severe depressive episode around six years ago. She did what she could in therapy and took prescribed medication. However, Tcholakian’s doctor soon diagnosed her with treatment-resistant depression, as the meds refused to work. Eventually, she began to deal with suicidal ideations.

“It was hard for me to function,” Tcholakian says. “I was losing jobs, my relationships were suffering, and I could maybe string together a few weeks, a couple months, tops, of relief.”

She began drinking — often alone — what for her was a hefty amount of booze: one bottle of Baileys a day. The routine “wasn’t cool or fun or sexy at all,” she says, noting that she just wanted to “feel less” and would do anything not to live inside her own dark, depressive brain. One day in October 2019, she dragged herself into an ER because the alternative was to take her own life.

For a couple months, Tcholakian slept on her father’s couch and just rested. COVID-19 hit the U.S. last spring as she was beginning to build her life back up, re-traumatizing her, she says.

“It was very easy for my brain to go to where it always goes, which is: You’re a piece of shit, look how weak you are that you can’t cope,” she says.

But through all this, nobody staged an intervention for her. The drinking just wasn’t sensationally bold.

“I believed that I didn’t belong at 12-Step because I wasn’t a gallon-of-vodka-a-day drinker,” Tcholakian says.

She started her recovery with Co-Dependents Anonymous meetings, but she also became a regular at an open-plan gathering for addicts of all shapes and sizes. It’s organized by the people behind a recovery-focused newsletter called “The Small Bow,” and many people at these meetings wonder, like Tcholakian, whether they’d fit in at more traditional, formal settings because their substance abuse has not ascended to what might be perceived by others as critical heights.

“It was one of the most important meetings for me in my early recovery,” Tcholakian says of the The Small Bow get togethers.

Tcholakian is now 14-months sober, and says she’s starting to come out of that six-year depression. She’s proud of her sobriety and sounds optimistic but admits there are still hurdles she must navigate constantly. When another addict she knows relapses, she says, “There’s a part of my brain that’s like: This proves you’re not really an alcoholic because you’re still sober … even though it is really hard for me to be sober.”

She’s also become the host of The Small Bow meetings.

“The intro that I read every week for the meeting is, basically, ‘If you suffer from issues related to drugs, love, sex, debt, codependency, just being a dick, whatever your issue is, you belong here, we’re glad you’re here and you can talk about anything you need to talk about here,’” Tcholakian says.

To be clear, she’s not denigrating any other recovery program. There’s every reason to believe any given Alcoholics Anonymous meeting, for example, would be more than welcoming to people existing in the middle of the addiction spectrum, and in fact Tcholakian now attends 12-Step meetings herself. But the group she hosts is in place partly to appeal to the self-conscious minds of those with less-severe substance abuse issues and who are nonetheless battling them in some way.

Social signals aside, another reason it’s so challenging for people like Tcholakian and James to recognize that their addition is that the term’s medical definition is relatively unrefined. The American Society of Addictive Medicine (ASAM) says it is “a treatable, chronic medical disease involving complex interactions among brain circuits, genetics, the environment, and an individual’s life experiences. People with addiction use substances or engage in behaviors that become compulsive and often continue despite harmful consequences.”

As pointed as this phrasing may seem, look closely and you’ll see plenty of gray area in the margins. First, “an individual’s life experiences” can vary no less than infinitely. Try nailing down examples of what exactly “compulsive” or “harmful” behavior looks like, and a lengthy trip down a rabbit hole of qualifiers is sure to follow.

It’s no wonder, then, that ASAM even used the word “complex” within its own definition of “addiction.” But people who think they might be addicts are perhaps better served studying the spectrum of addiction, which narrows the definition into three categories.

Laura J. Veach, Ph.D., co-author of The Spectrum of Addiction: Evidence-Based Assessment, Prevention, and Treatment Across the Lifespan, places the terms “risky,” “moderate” and “severe” on what she calls “a continuum” of addiction stages — though individuals could take up residence in a single stage for years, with various levels of risk. (Veach falls back on alcohol abuse as a focus for examples because, she says, it’s the substance that’s been most heavily researched, but many of these concepts are transferable to discussions about other substances.)

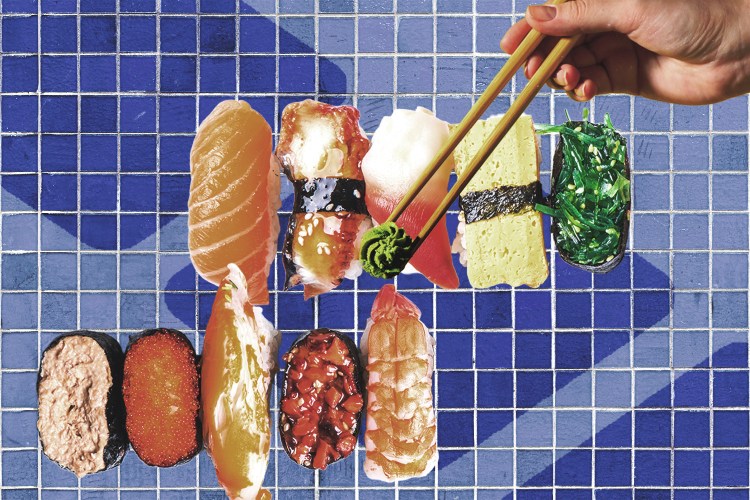

Painting in broad strokes, Veach says “risky drinking” involves intermittently binging to the point where the chance of harm is raised, including physical injury or the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases during ill-advised, inebriated intercourse.

“Moderate” addicts, she says, might have around half of the 11 symptoms that the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM–5) outlines in describing “severe” addiction. Frequent hangovers could be a sign of moderate alcoholism, Veach says, or a growing preoccupation with drinking — “thinking about the next time I’m going to get together [with friends] and get a keg, and I’m going to make sure I get enough” — may be another.

Should a person enter the “severe” end of the spectrum, they’re experiencing more of the DSM-5 symptoms, including a high tolerance and withdrawal effects on the body. Veach also says, citing another doctor’s study, that measuring the problem doesn’t have to coincide with the amount of drinking a person does. Instead, it could have to do with the number of times or the ways they’ve tried to cut back, how annoyed they get when others express concern over their drinking, the guilt they might have about their drinking, and whether they’re using their substance of choice to simply “get going in their day.”

Still, “you can’t define it by one symptom,” Veach says. “People try to say, ‘Well, I don’t have blackouts, so I can’t be [addicted]’ or ‘I don’t have withdrawals, so I can’t be addicted.’ No, that is not true.”

These people likely just belong to one of the less-severe categories of the addiction spectrum, which account for the bulk of prospective addicts in society. Of the 65 percent of people who consume alcohol, just nine percent fall into the category of drinkers at a “severe” risk, according to Veach, who cited various sources, including the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. Everyone else who drinks falls below that severe-risk level and will not have many outward signs of having an issue.

I ask Veach what concerned people can do to help themselves figure out whether or not they are an addict of some standing. Her response?

“Stay curious and explore that [compulsion]; learn about hangovers [and] alcohol’s impact on the physical being,” she says.

In the mind of Rachel Schwartz, the Brooklyn-based addiction counselor, hearing a client say anything to the effect of, “I just want to know that I’m in control” sets off an alarm.

“I feel like that’s such a common thread for the middle-of-the-spectrum people,” Schwartz says. “It also takes some insight to consider Do I have control over this?”

Ultimately, it’s up to each individual to answer the question of whether they’re an addict. If you do your research and reflect upon your behaviors, you might be surprised by where you fall on the addiction spectrum.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.