In his running memoir What I Talk About When I Talk About Running, Haruki Murakami shares an anecdote about interviewing marathon legend Toshihiko Seko. He once asked the runner, “Does a runner at your level ever feel like you’d rather not run today, like you don’t want to run and would rather just sleep in?” According to Murakami, Seko looked at him like it was the stupidest question he’d ever heard and replied, “Of course. All the time!”

When I quit running almost 10 years ago, I’d never read Murakami’s memoir. But I’m sure I would’ve been surprised to see Seko’s apoplectic reply. I never had the talent to run in the Olympics like Seko did — his best 5K is a blistering 13:24, and his top marathon time stands at 2:08:27 — let alone compete for a Division I school. At my best, I was running varsity-letter times for an above-average public track program in suburban New Jersey. But I did it for years, and that distinction is important, because it more accurately captures the grind of running on most days of most months. There is beauty in mundanity, but running’s mundanity is unusually confronting. Each month presents its own challenges: icy patches in January, mornings that hit 90°F before you leave the house in July, weeks in April and May with so much rain that your running shoes never truly get dry. Each day and each season hurts in its own special way. Before I’d ever voted or had a beer, I’d gotten used to trudging up steps like the old man from Up, my legs resigned to an always-there ache.

There are probably days that basketball players aren’t keen to shoot 100 free throws in a row, and afternoons where tennis players would rather not hit three baskets of serves. But at least in those sports, the endgame — an actual game — is justification enough for the work. With running and other endurance pursuits, training is uncomfortably similar to competing. It can prove difficult, especially at a young age, to retain enthusiasm for the sport. By the end of my first running life, my personal odometer somewhere north of 7,000 miles, my legs were mush and my brain was in even worse shape. I lacked self-confidence, I lacked body confidence and I had little will to run, let alone run hard. I figured these were me problems. I wanted nothing more than to hit the snooze on my alarm and skip my next tempo run. And before I read Seko’s confession, it would never have occurred to me that gold medalists feel the same way.

Over the past seven months, I’ve started running again. I suppose there’s been a bit of fanfare; I’ve certainly written about it in detail for this publication. But running’s return for me — its leap from rediscovered hobby to ritualized necessity — wasn’t so dramatic. Early on, I just realized it was something I wanted to do again. It was for me. There is a new, flourishing subgenre of people writing about things that “keep them sane” during quarantine. But running has given me far more than sanity this year. It’s given me a change of scenery. It’s brought me happiness. And most importantly, it’s proposed a different way to chart the passage of time, in a year in which that concept has rapidly lost meaning. Runners, like everyone else, monitor calendars and newsfeeds and weather. But the lifestyle also allows for an alternate theory: time measured in progress.

As that progress began to pile up for me a couple months ago — a successful six-miler here, a not-too-terrible hill workout there — I began to think about my best prep times. I’d long figured them untouchable. But why, I eventually decided, shouldn’t I make a run at the glory days? A lot has happened in the world of running over the last 10 years as a direct result of a lot happening in the worlds of recovery fitness, nutrition, performance tech and mental health. With the blessing of relative youth on my side (I’m 25, but the opportunity window for personal bests in endurance events is longer than you’d think), I began to apply those developments to my training mindset, and formalized a specific goal. I wanted to summit an old, familiar, painful mountain. I wanted to run a sub-five-minute mile.

Spoiler alert: I did it. Comfortably. The following is a guide to the exact methods that helped me get there. It should go without saying, but I cannot guarantee that everything outlined here will work for you. These are practices that helped me achieve my specific goal. Not to mention: running, like playing the cello or cooking a soufflé, requires a degree of natural ability. Still, all prospective milers have a time they’d like to turn their back to (be it 10:00, or 5:00) and I’m confident that these practices — from strength training to slugging back cups of beet juice to investing in a pair of carbon-plated trainers, will help runners of all levels.

Why the mile?

It’s back. Not that the mile has ever really left. It’s still a fitness benchmark for elementary schoolers and lazy coaches at sports-team tryouts. (In high school, our track team used to enjoy cheering on the infamous “tennis mile” each year.) At the professional level, it’s a middle-distance kingmaker, despite not being run at either the Olympics or World Championships.

A contemporary star like Oregon alum Matthew Centrowitz, who won gold in the 1500-meter race at Rio in 2016, isn’t even celebrated for his success in that event, but for his potential in its closest cousin. In 2017, SB Nation mused that Centrowitz might be the best American miler ever. The running world is deeply protective and endlessly nostalgic about four laps around a track. The mile is the lone surviving imperial distance in the world record books, and there are campaigns to make it a cultural movement again. Similar to astronauts, famous milers (like Jim Ryun, John Landy and Sebastian Coe) used to ride their achievements directly to public office. It’s hard to imagine the distance reaching that level of recognition again, unless a runner were to electrify the world and break Hicham El Guerrouj’s mark of 3:43, set in Rome 21 years ago. For now, heat after heat of talented runners continue to try: at the Bowerman Mile, the Dream Mile, the Fifth Avenue Mile, the Hoka One One Long Island Mile and the Wanamaker Mile.

For amateur runners, though, the mile has long felt unapproachable. The average age of American runners climbed a full four years over the last three decades (from 35.3 to 39.3), and the preferred distances of those men and women leans longer, towards 10Ks, half-marathons and marathons — all areas of expertise that demand less speed, feature thousands of competitors and make it easy to compare times. A proper mile, by contrast, feels like a sprint. It generally necessitates a track. There is no sea of competitors to hide in or rely on for a quiet, “respectable” finish. It can feel like a niche, unnecessary pursuit, with very little upside.

But recent developments have shuffled that impression. For one, it’s increasingly accepted among the running community that too many endurance training programs are ignoring the significance of training for power and speed. This despite the fact that running fast, no matter your age, will actually help fortify the body for all those hours of running slow. Speed training encourages the development of “fast twitch” muscle fibers, which help your muscles operate more efficiently during the wear and tear of long-distance running. As more runners get used to quick, uncomfortable workouts, the mile run seems like less of a boogeyman.

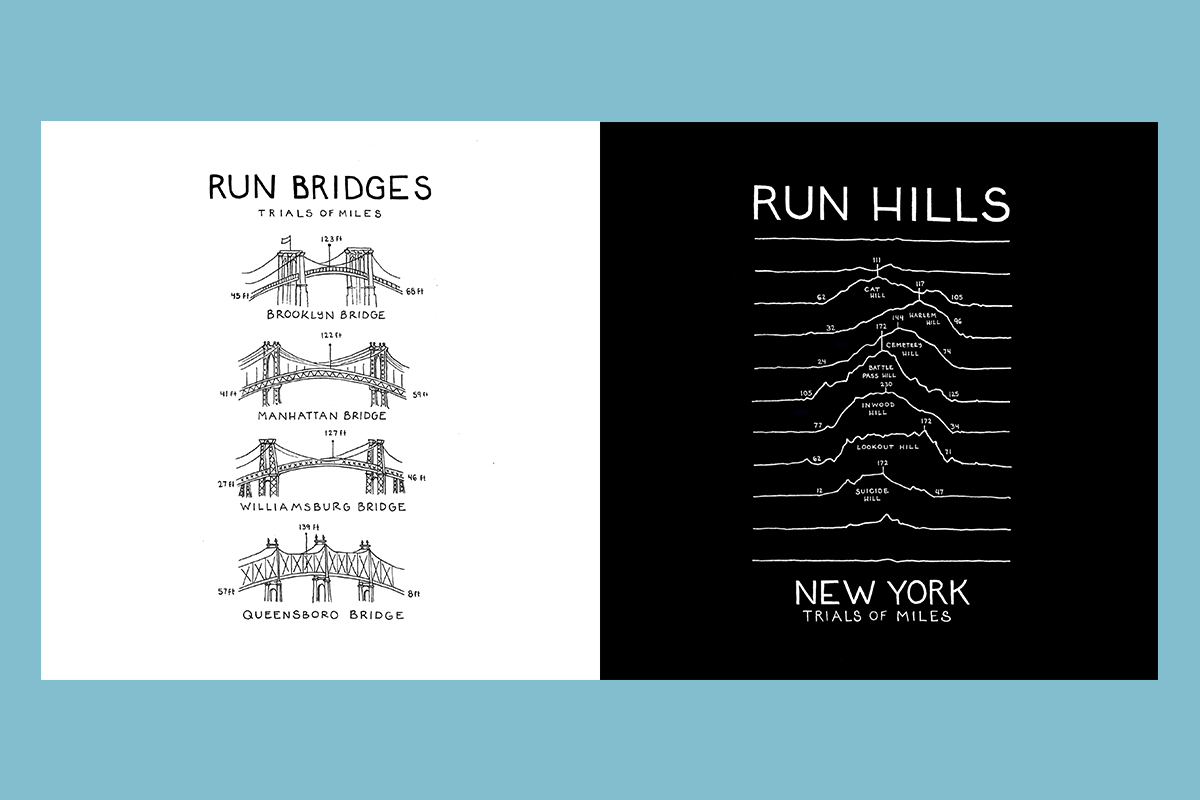

Event operators have taken notice, and put the mile’s portable, turnkey ease to use during the pandemic. Unlike all those canceled 10Ks, 13.1s and 26.2s, an outdoor mile doesn’t have course-specific declines or uneven terrain; it’s four loops around red polyurethane. As amateur runners have started to care about the mile again, they’ve signed up for virtual mile runs — like the ones hosted by Tracksmith, running collective Trials of Miles or Brooklyn Running Co. — and had more marks to compare their best against. The discipline is no longer the express domain of teens angling for a spot on the JV tennis team or Moroccan mile extraordinaires. In the 2020 Virtual BKLYN Mile, for instance, a man from Yokohama, Japan, beat a man from Massachusetts for the top prize. Both were under 4:10. But just as impressive, and inspiring, were the amount of runners over 50 years old running miles under 5:00.

The training methods that helped me run a 4:51

Before I’d really started running again, at some point late last year, I rolled over to a track and ran a 5:59 mile. I’d eaten a bagel sandwich an hour before, and most of it ended up on the field promptly after my finish. Nothing about the run had felt good: not my first lap, which, for most successful milers, is an adrenaline-fueled blur. Not the watch-staring I’d done for the second half of the race, concerned I’d end up over 6:00, or the kick I did at the end to eke myself under. The northwest curve in the track was windy, like the tunnel the subway creates as it hurtles by. I found myself powerless against it, a bobbing inflatable at a used-car dealership, straining in my outdated, too-tight trainers, wondering desperately how I’d ever managed to move my body any faster.

I made some mistakes, starting with my decision to dive directly into the time-trial deep-end. Race-day simulations are tempting and provide a frame of reference, but without proper preparation and an accompanying training plan, they’re unfair — To your cardiovascular system. To your leg muscles. To your breakfast.

Soon after that bout with mediocrity, I decided to take my running more seriously. If I was going to lower my mile time (or any time), it wasn’t going to be from catching the track by surprise. Over the next several months, I tinkered and refined a weekly running template which morphed into this:

- Monday: 5K Workout. I run a 3.1-mile loop at 80% effort. The last mile sometimes veers closer to 100%. I’ve made my peace with that.

- Tuesday: Longer Run. Five miles at a “good” pace. It’s a subjective term, but it essentially means the run should never turn into recovery pace. Slightly uncomfortable, but not too challenging.

- Wednesday: Hill Workout. Distance varies here. I might jog a six-mile loop that features a variety of different hills, and surge each time I reach the incline. I might run a three-mile run with a few choice, steep hills and run fast from start to finish.

- Thursday: Rest Day.

- Friday: Tempo Run or Track Workout. It depends on how my legs feel, and what sort of mileage I’ve accrued. I keep my tempo runs under four miles. Track workouts follow a simple format: 16 x 200s, 8 x 400s, 4 x 800s, or 2 x 1600s.

- Saturday: Easy Run. Fire up a podcast and run longer and slower. I’d go up to 10 miles, but preferred to keep it closer to six.

- Sunday: Rest Day.

The first thing you’ll probably notice, especially if you have a “26.2” sticker on the back of your car, is that this isn’t a lot of mileage. It can amount to as few as 20 miles over the course of a week. In marathon training, 20-mile runs are essential in a single day, especially in the five weeks before tapering begins. But the above, I’ve come to believe, is suitable boilerplate for the amateur middle-distance runner. If I started loading up my legs with 50-mile weeks, I’d fatigue eventually, both physically and mentally. Sure, it would honor everything I was ever taught about long-distance running (on our “rest days,” we were encouraged to run a slow 10 miles), but at what cost? And for what purpose?

Running less, and faster, keeps me safe from injury and engaged. My rest days, meanwhile, are true rest days from running, and afford me more time to focus on strength training — a practice I never considered last time I was running regularly, when my arms were the size of Ticonderoga no. 2s — and cross-training, an essential practice for reminding the muscles that there are ways to exercise beyond pounding one foot after another onto hard pavement. For weight training, I focused primarily on upper-body strength three times a week (through pushups, pull-ups and rows with dumbbells and resistance bands) to better my “arm drive,” which is critical in running, especially at shorter distances. I’d also pepper in bite-sized core and lower-half workouts (think planks, medicine ball work, jump roping, farmer’s carries, lunges, calf raises and squats) throughout the week or after my workouts to strengthen the spine and fortify the joints. For cross-training, I would take a bike out for a few miles.

These concepts comprise a new-ish, holistic approach to a running life, in which the absence of running is sometimes a runner’s best friend. While I remained active on those two rest days (work is sitting enough — I need to move around at some point, no matter what), I made a point to help my leg muscles along the road to week-over-week recovery. That includes four precise methods:

- Theragun Mini: I reviewed this little device in detail a couple months ago after it dropped. If you’re serious about running and recovery, there’s no reason not to own one. I use it every day.

- NormaTec: Massage boots. You strap these on and they administer a deep-tissue contract-and-release massage over a time period of your election. My legs feel like pudding after, in the best way.

- Runner’s High Herbals: A line of recovery lotions and ointments from some adventure athlete-herbalists, who mix wild ingredients like arnica flowers or cayenne peppers with menthol. I rub this stuff into my calves a couple times a week.

- Cold showers: Self-explanatory, but exposure to extremely cold temperatures has all sorts of magical health benefits, like lowering blood pressure, stimulating the immune system and staving off injury. I end most of my showers with a minute of freezing cold water immersion.

Trite, but true: progress is addicting. Not long into this process, I started to think about ways I could move myself along on days when I wasn’t literally moving down the road. It proved crucial, and helped destabilize a commonly held notion in running that only more running is more. Don’t get me wrong — some of those hard days in my weekly template were really difficult. The 3.1-mile loop on Monday isn’t easy. The track workout on Friday is a slog. But I felt better recovered from them thanks to these recovery methods. And I felt better prepared for them thanks to some dietary decisions I’ve made over the 10 months or so. The most prominent change I made, last November, was cutting out meat. I am convinced that this has helped me regain a ton of ground in running in a surprisingly short time. I won’t soliloquize the reasons for my decision, nor the purported benefits of the switch, but it seems reasonable that a reduction in blood pressure, inflammation and indigestion has given me more energy. I’ve certainly felt it.

My diet includes bagels and pizza and blueberry muffins and (fake) burgers like everybody else, but now leans a bit — in the court of public opinion, at least — banal. I mainly eat fish and rice and vegetables and fruit. I’ve had less to drink this year, too, due to the bars being closed. Aside from the obvious advice for better, exercise-conscious consumption — choose your pre-run meal carefully, prioritize plant-based meals and purchase products with shorter ingredient lists — my one absolute wild card of a recommendation is to start drinking beet powder. I wrote about my experience with the vegetable as a pre-workout supplement last month; it’s off the charts for nitrate levels, which help encourage vasodilation in blood vessels, making it easier for your heart to pump blood around the body. I mix the stuff in a glass of water and chug it back every single day. It tastes disgusting. I feel great.

The trappings and triumphs of “race day”

Runners tend to break down the mile into 400-meter splits. You can subdivide further and check for 200-meter times throughout the race (anything under 30 seconds is really fast), but generally it’s lap-by-lap times, spoken as a counting number, like “75 seconds.” To run a five-minute mile all you have to do is run a 75 four times in a row. To break it, just one of those laps has to duck under 75. When I headed to my local track in early June of this year intent on breaking five for the first time in a decade, that was my race plan: run three 75s, then gut out the last lap and see how far under I could go (if at all).

When I got to the track that Friday afternoon, I’d had some recent experience with finding my “race day” demeanor. It’s funny — I left the sport for almost a decade, and the year I chose to come back, all road races were promptly postponed or canceled. But during my training, I’d competed in some virtual events and ran a 5K at a promising pace, so I felt reasonably confident that the time was within reach. In addition — and I’d recommend this for anyone looking to shave significant time off their mile — I’d familiarized myself with exactly who I needed to become in order to run fast. Sustaining speed over time is a dark pit of hell, and it’s important to have at least an inkling of what it feels like before jumping into it when everything suddenly counts.

For me, that meant lining up workouts at the end of the week, when a searing workout, oddly, felt like a reprieve from 50 hours of work. It meant creating a playlist of uptempo bangers (a luxury I’d never had in my school days) to take the edge off the laps. And it meant growing comfortable with the fact that racing against a time in the midst of a pandemic is a lonely experience with little accountability. There probably isn’t a coach or spectator to keep you in line or prevent you from quitting when the race isn’t going your way, let alone a pacer, or even a competition, to propel you toward the promise of crossing the line first.

In other words: running a mile as fast as you can, entirely by yourself, kind of sucks. But coming off months of effort, it’s also exhilarating. I picked a day and time when it hadn’t rained and my track wasn’t wet from the town sprinklers (which occurs frustratingly often). I warmed up with some dynamic stretching (more on why that is preferable to static stretching here) and a couple laps before digging into the starting line. And then, without even a glance from the septuagenerian doing jumping jacks in a shady corner, I was off. This time around, all these months later, the first lap flew by. I felt light, a little giddy, definitely overexcited. I crossed the line in a 72. The next lap I found the correct pace, reeling myself back with a 75. I was two seconds better than my goal, with two laps to go.

On the third lap, as is common with most milers, I fell apart a bit. There’s a bit of an unavoidable urge to conserve energy in deference to a dramatic kick for the final lap. Plus, you’re tired. I scraped across a 76. But that faded when I passed the start line for the last time, took a look at my watch and did some mental math: I’d crossed in 3:43, which meant another 76 (!) would be enough to break 5:00. But I felt better, I realized, than a 76. All that speed-work (and all that rest) had paid off. I shortened my stride turnover, pumped my arms and pushed forward, not even bothering to check my watch at the 1400-meter mark. When I finished and jabbed at my watch, the lactic acid in my thighs utterly unbearable, the time read 4:51. I’d run a 68. And for the first time in a long time, I was back under 5:00.

A few minutes later, while I was lying down on the track feeling a bit like I’d been hit by a truck, jumping jacks power-walked past me.

“Easy day, huh?” he chuckled. “What’d you do?”

“The mile,” I replied.

Now more than ever, gearheads are rewarded with better times

No long list of acknowledgments here: pandemic training is as personal as running gets. I’m proud that I figured out a way, on my own, to get below 5:00. Pardon the clichés, but it all came down to making a plan, trusting my instincts and knowing when (and when not) to push forward. Next up are my official personal bests, which are 4:45 in the mile and 10:08 in the two-mile. The latter will require a slightly different routine, and I’m not sure I’ll even get to it this year. But I look forward to taking some shots at it down the line.

All of that said — I benefited, big time, from running’s recent, open-secret, no-turning-back collision with performance tech. I was reminded, when doing research for this story, of a piece by Wired Editor-in-Chief Nicholas Thompson, who wrote about logging his best marathon times in his forties thanks in part to an unfettered embrace of technology. He discusses heart-rate monitors, shoe-sensors that measure pronation, blood work to test oxygen-consumption rates and apps that catalogue and share every workout. Regardless of your preferred distance, this is running in 2020, and amateurs are on the front lines.

It can be intimidating to know where to start, or even how to feel about this revolution (Does harnessing the arsenal of available tech lead to “artificial” personal bests?). But the reality is that it’s there, and it’s not going anywhere. I’d urge an open mind, and starting slow.

Some of the most crucial gear I used during my quest for a sub-five mile was simple and timeless, like a race-day Nalgene or a pair of running shorts that sit just right. My favorites are from Tracksmith; they’re made of a stretch-knit Italian fabric. But the developments that definitely brought me over the top are specific to the last few years, like the advent of run-tracking app Strava and carbon-plated shoes. I relied heavily on Strava as a public notebook, a data-collector and an accountability check throughout my training. (It’s also just fun.) And when I ran that 4:51, I ran it with a pair of Saucony’s Endorphin Pros on my feet, the latest and greatest effort by a big running brand to manufacture faster times with absurdly responsive, absurdly tall shoes. When the movement’s poster boy, the Nike Vaporfly, first took over the running world 18 months ago, one writer compared the shoe’s Pebax foam to having a second leg muscle.

It’s possible to eclipse a certain time without a pair of fancy shoes. After all, 10 years ago, I broke 5:00 in a pair of uninspiring Nike flats, and 70 years ago, Roger Bannister broke 4:00 while running in what might as well have been tap-dancing shoes. But modern racing trainers, like the Asics Metaracer and especially the New Balance FuelCell 5280, are designed with middle-distance scampering in mind, and are meant to improve running economy along the way. Running is hard enough; embrace the toys. That includes the recovery machines I mentioned earlier, and all the other monitors you’re sure to happen upon or will come along as the years wear on. Just save some of your paycheck for groceries.

And when your mission to shave time off your mile hits a snag, remember: if you’re not feeling up for it, if you’d rather sleep in a bit longer, you’re not alone. If a barrier proves to be too much, you can always save it for later. Just come back in 10 years or so. It’ll be right there waiting for you.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.