During the month of April, we’re publishing a series of interviews, essays, advice columns and reported features about the male friendship crisis in the U.S., a particularly troubling slice of the country’s larger loneliness epidemic. There’s no one-size-fits-all solution, so we’re breaking it down from all angles in The Male Friendship Equation.

Sitting in the back patio of a hip bar in my hometown of Astoria, Queens, a woman in her late 20s cuts a charming profile in the doorway. She beams a smile in the direction of a big, attractive bearded guy of about the same age at another table. As she steps down into the space, he grins back and quickly gets up to greet her. But his hulking thigh punches the rickety plywood table in front of him, sending nearly all the hoppy contents of his pint glass to an early demise.

It becomes clear with a hug and nice to meet you exchanges that Charming and the Beard are beginning a first date. “Not the coolest way to start,” I say to Jason, who’s sitting across from me.

“Yeah, that’s rough,” he says, shaking his head, amused as the guy awkwardly returns his glass to an upright position.

Taking it in stride, though, the woman casually leads him back to the bar for more drinks.

“Ah, he can take a hit like that and survive,” I say. “He’s tall and good-looking.” Jason agrees.

What Jason hopefully doesn’t know is that I was nervous myself upon meeting him for the first time earlier this evening. We’d initially connected, almost certainly like the other pair, on an app. But instead of looking for a romantic relationship, we’re just two straight dudes hoping to become buds with the help of Bumble For Friends.

App to BFF?

Jason (not his real name, like everyone else in this article) is an artist in his mid-30s. He currently lives upstate but thinks a move down to the city will help boost his career as a creative. I’m a 45-year-old writer who’s vertically challenged (hence my fixation on the bearded guy’s height), but I know one of New York’s relatively affordable nice neighborhoods exceedingly well. I offered to be an Astoria tour guide to Jason after a handful of messages between us on Bumble For Friends, a platform that looks and feels identically like the popular dating app Bumble, but is intended to foster platonic relationships. Jason accepted, and after a subway ride from the Midtown Manhattan office where he works part-time, we were shaking hands on our way to grab some Thai food.

Over massaman curry he tells me he’s used Bumble For Friends on and off for a year. Networking and art collaboration opportunities are Jason’s main end goals, but he’s also seeking out new friends. He’s moved around a bit in recent years, and the app affords him access to people in the small Hudson Valley city where he lives, as well as thousands of others well beyond its perimeter.

He hasn’t had tons of luck, and on multiple occasions he’s done the same thing many others do during bouts of frustration and burnout with dating apps: delete it for a while, then reinstall it. But apparently I’m a strong candidate for friendship, and other guys I’ve interacted with on the app say they have successfully started new platonic relationships using the platform, too — a good thing, considering there’s a male “friendship recession” happening right now in America.

Read the Full Series Here

The Male Friendship Equation: Stories, Interviews and Advice During an “Epidemic of Loneliness”

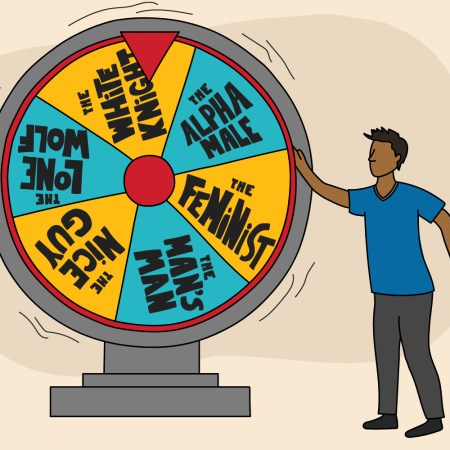

American men are in the midst of a friendship crisis, so we’re turning our attention to these all-important platonic relationshipsPer an oft-cited survey, the percentage of U.S. men with six or more close friends nosedived from 55% to 21% between 1990 and 2021. The percentage of U.S. men who report zero close friends also leapt fivefold, from 3% to 15%. All of this data is concerning because loneliness increases the risk of heart attack, stroke and even premature death, among other physical health problems, to say nothing of the extensive list of mental-health issues that may come with isolation as well. There are a number of theories that could explain why today’s men struggle to make and maintain friendships, but many experts blame social norms that teach boys and men to value toughness and stoicism over being vulnerable, which is one of the primary ways people build trust, empathy, honesty and other hallmarks of productive, enjoyable relationships.

“In our culture, men have been socialized to compete in all areas of their lives, as if it is all a zero-sum game,” says Wayne M. Levine, founder of BetterMen Coaching. “Additionally, the disappearance of male social groups eliminated the place where many men had traditionally gathered professionally and socially. All of this has left generations of men isolated and lonely. At the same time, our society has not been terribly concerned with the feelings and experiences of men [and] that sense of isolation was only compounded by the pandemic.”

Fortunately for me, I don’t fall into the friend-deprived category, probably because I’m very open about my thoughts and feelings at any given time. (If anything, I often wonder if I need to rein that in a bit.) Without putting much thought into it, I can rattle off the names of nine people I deem “close friends.” I would venture to guess that the number of people in my life who I define as friends — those with whom I keep in touch at least fairly regularly — easily exceeds two dozen. And that number has been growing.

Two summers ago, while writing a story for InsideHook, I became obsessed with soccer. I joined a supporters group linked to the Premier League club Manchester City, went to their match watch parties and joined in the carousing. Over time, I’ve gotten to know a few fellow members pretty well, scoring an invite to a New Year’s Eve party from a group of them, and attending baseball games and movies with another member, who’s nearing “close friend” status, if he isn’t there already. Through another soccer-obsessed friend I also recently met the co-founder of a supporters collective that pulls for Man City rival Arsenal, and just a few weeks ago, members of our respective groups squared off in a series of soccer matches I coordinated. I’ve also organized New York watch parties of games played by Major League Soccer club the Columbus Crew.

It’s important to illustrate all of that, not to prove to myself (or anyone reading this) that I do indeed have friends, but to show that I’ve worked hard to make them. Friendship isn’t a thing that just happened to me. After putting in the work of seeking out friendship through multiple apps, it appears I may have made even more pals.

Not Here to Make Friends

There’s Jason, who after bringing him to a Thai restaurant in Astoria didn’t seem to mind walking back in the direction we came to nosh on some Greek pastries, before we then traveled back the other way toward a neighborhood retail thoroughfare — maneuvers I anxiously perceived as pain points in my itinerary. He enjoyed all of it, said he’d keep in touch and is strongly contemplating a move to the area.

I also met a movie lover in his mid-40s. We’ll call him Mark. We exchanged a bunch of texts about the films we enjoyed last year in the run-up to the Oscars before grabbing caffeinated drinks to get to know each other better and discuss his experience on Bumble For Friends. Mark is gay and has been on the app for a year, making two friends, who are also gay, before matching with me. Prior to committing to his boyfriend, though, he hooked up with other guys he met on the supposedly platonic app, an outcome that appears to be commonplace across the platform.

As I go through the profiles, it seems a slim majority of the men have marked off “Out and Proud” in the section labeled “My Life.” I message with another married gay man on the app who tells me, “I’m looking for friends, [but] everybody either doesn’t want to meet or wants to fuck.” Jason says he’s also aware that Bumble For Friends, at least in the New York area, is partly a playground for gay hookups. Another straight friend of mine told me that a number of gay men have propositioned him with sex on the app. Mark understands that kind of “cosplay” would be “unwelcome” for straight guys.

I remark that the night is really starting to feel like a season premiere of The Real World.

Mark also tells me he has matched with straight men, but chats with them always seem to peter out before a real meetup occurs. Outside of my interactions with Jason, this was the case for me, too.

“Most straight men don’t seem to want to find friends this way,” Mark says. “Gay guys don’t really care, even if we’re not deliberately looking for anything romantic or sexual.”

I ask Mark if that’s because dating apps are more ingrained in LGBTQ, rather than heterosexual, culture. “I guess you can say that,” he responds. But for friendship to work, Mark adds, “you need to say, ‘I feel a connection with this person,’ and that’s a weird dynamic if it’s truly, totally platonic.”

Dinner for Four

Besides Bumble For Friends, I also try Timeleft, the friendship app that arranges dinners with strangers. Launched in Europe two years ago, Timeleft is new in New York. The user experience starts with a lengthy multiple-choice questionnaire. “Are your opinions usually guided by: ‘Logic and facts’ or ‘Emotions and feelings,’” goes one query. “Do you consider yourself more of a: ‘Author’s film enthusiast’ or a ‘Mainstream Blockbuster Lover,’” says another strangely worded question.

Next, you rank yourself on a scale of 1 to 10 whether you “Strongly Disagree” or “Strongly Agree” with a series of statements. There’s “I am an introverted person,” “I am a self-motivated person,” “I am a creative person” and “I am a stressed person,” among others. (Hedging my bets, I punch “7” on that last one, lest anyone think I’m a total mess.)

After paying $16 for a ticket, I arrive at my Wednesday night dinner in a terrific, moderately priced vegetarian restaurant on the Lower East Side. Andrew is sitting at our table already, and we immediately bond over our love of Seinfeld after I make a referential joke that the restaurant is located on First Avenue and First Street, “the nexus of the universe.” Andrew is also into soccer and, for now, living off money he made in smart investments. (I want to joke that he’ll be covering my dinner, but I bottle that up.) In comes Derek, who’s employed at a law firm, but also dabbles in photography, followed by Leah who works in product design. I remark that the night is really starting to feel like a season premiere of The Real World.

The four of us disclose some details about our lives and our worries about the world. We’re all about the same age, and we’re all single. The discussion flows smoothly, and we answer some of the app’s ice-breaker questions, like “What’s your all-time favorite song?” — to which I embarrassedly answer “Where the Streets Have No Name” by U2. Thankfully, my tablemates confirm that, even if it’s corny and obvious, that’s only because it’s also a banger.

Fagin says men have to “be willing to make that effort” to connect with people out in the world, “be willing to take that risk” of being vulnerable in the presence of others, in order to forge rewarding friendships.

At one point in the evening, Leah says she approached the Timeleft app experience with friendship top of mind, but was also open to the idea that if she met a man and there was a romantic spark, hey, so be it. (I don’t say this, but I thought the same thing.) Leah’s recently divorced and looking for friends to go on hikes with; at one point, Derek says that it feels to him like New Yorkers “reset their friend groups every 10 years.” (Reflecting on my life, which included a critical career change a little more than a decade ago, I mostly agree with that assessment.)

We figure out there is another Timeleft group at the restaurant, composed entirely of people around 15 years younger than us. We call them the “kiddie table.” I ask the kids if they’re hitting the bar where the app is encouraging everyone to gather after dinner. They are, and so are we. Turns out, so was another Timeleft dinner party at a completely different restaurant. Over the course of the next couple hours, the three groups all blend together.

But the only people with whom I exchange contact information — just emails — are my original three strangers. Derek tells us about a platform that organizes small, affordable classical concerts in people’s homes, and we all vow to try to meet up at one someday soon. I think we will.

A Jumping Off Point

I suppose time will have to tell whether or not I had true success on these friendship apps, and not enough of it has passed before I can say with certainty. But the initial results are promising. I’d give a stronger stamp of approval to Timeleft than Bumble For Friends. I like the concept of Meetup, too, the platform where users generate events with any focus a person can conceive. (I got my whole journalism career kickstarted at a Meetup event, where I connected with the first publisher who paid me to write, for what it’s worth.)

Like Timeleft, Meetup gets people off their couches to more intimately exchange energies with other living, breathing, talking, laughing, crying human beings. Those interactions feel more earned and, I think, will generally have a greater return on investment for folks on the friendship hunt. If part of the reason men don’t have friends is because we are increasingly isolated — thanks to the pandemic, but also due to the emergence of online relationships and work-from-home arrangements — a phone app that essentially gamifies friendship from the comfort of one’s home isn’t going to change that. If anything, it could continue to perpetuate such a state.

Levine, the life coach, says his go-to suggestion for men looking to develop platonic male relationships is to join a men’s group of some kind that gathers together in person. They can easily be found online. He also agrees that Meetup is another viable option.

“Spending time with the same circle of men on a weekly basis allows men to learn about themselves and make changes in their lives while they build trusting relationships with each other,” he says.

Though he’s not opposed to friendship apps if they do in fact help, Levine’s first “visceral reaction” to the concept of them was not a positive one. “That somatic feeling I had suggested to me that men of a certain age, perhaps 40s and older, might have a lot of resistance to these apps,” he says. “Men have a difficult time asking for help of any kind. Appearing weak in front of other men is what keeps them isolated. It will be interesting to see if this technology will have its desired impact.”

For Martin Fagin, Ph.D., a clinical psychologist at New York City’s Madison Park Psychological Services, male friendship apps are “one tool you can have in your toolbox, particularly for people that have social anxiety or a disability.” Fagin adds that individuals who live in rural areas and don’t have a great degree of access to people could also benefit from friendship apps. In his mind, friendship is best cultivated in settings where people feel safe enough to be vulnerable, and apps can help facilitate that sense of security through their screen-to-screen vetting process.

But Fagin says men have to “be willing to make that effort” to connect with people out in the world, “be willing to take that risk” of being vulnerable in the presence of others, in order to forge rewarding friendships.

“That’s the part that oftentimes people miss,” he says. “People don’t even realize that they’re scared, and particularly when we take on the stereotypical male schema, even if you did realize you were scared, you would quickly try to suppress that because that doesn’t jive with your masculinity.”

He adds that men must acknowledge their fear and should discuss it freely. “It doesn’t make you weak to acknowledge that you have fear, it makes you human,” Fagin says.

So if you’re a guy who’s experiencing a dearth of friendship, try and push through whatever social anxiety you might feel and just talk to other men — on an app, “in real life” or both — and remember to really open up. Chances are good that whoever you connect with will be in need of a friend, too.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.