A malaria parasite that is resistant to a widely-used drug combination is on the move in Southeast Asia. It moved from Cambodia to northeastern Thailand to southern Laos, reports Science Magazine, and is now in southern Vietnam, where there is an alarming rate of treatment failure.

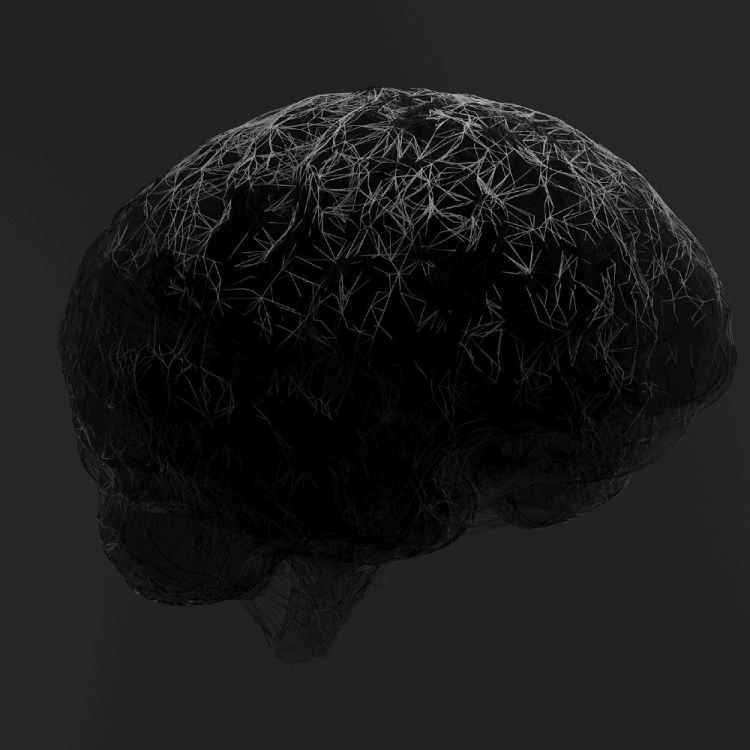

The Mahidol Oxford Tropical Medicine Research Unit in Bangkok writes that this strain is becoming dominant in parts of the Greater Mekong subregion. In the October issue of The Lancet Infectious Diseases, researchers write that this is bad for the region but also because the bug could spread from there to Africa, where more than 90 percent of malaria deaths occur, according to Science. If it were to spread, “consequences could be disastrous.”

Nicholas White, the head of the Mahidol group, has urged the World Health Organization (WHO) to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern. This designation is made only for serious outbreaks of diseases that could pose a global threat, Science writes. The letter triggered media stories of a “superbug” but WHO dismissed the report as “nothing new,” reports Science.

“Parasite resistance to antimalarial medicines is a serious problem. But we must not create unnecessary alarm,” said the head of WHO’s Global Malaria Program, Pedro Alonso, according to Science.

Critics are not disputing the group’s genetic studies of the malaria parasite, but disagree on when to call it a disaster. Dyann Wirth, a malaria researcher at Harvard University, chaired a WHO panel in December that reviewed the group’s earlier data. He said that it has “not reached the proportion where the world should panic.”

Drug resistance is a little complicated. The drug to fight malaria is essentially a one-two punch. Artemisin wipes out the parasite in hours, while the longer-acting partner, like piperaquine, kills any remaining strains. When parasites are resistant to the artemisinin component of the drug, Science writes, the drug still works, but more slowly. But when resistance to piperaquine emerges as well, the treatment fails. The patient will get better at first but get sick again a month later, according to Science.

Arjen Dondorp of the Mahidol group thinks that resistance to partner drugs will happen quickly, which would raise the prospect of untreatable malaria, writes Science. But WHO’s expert group took issue with many of the claims, also saying that the risk of it spreading to Africa “cannot be discounted,” the likelihood of the parasite taking off in a new environment is low.

Dondorp told Science that he is worried the constant bickering and conflicting ideas will “lower the sense of urgency.”

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.