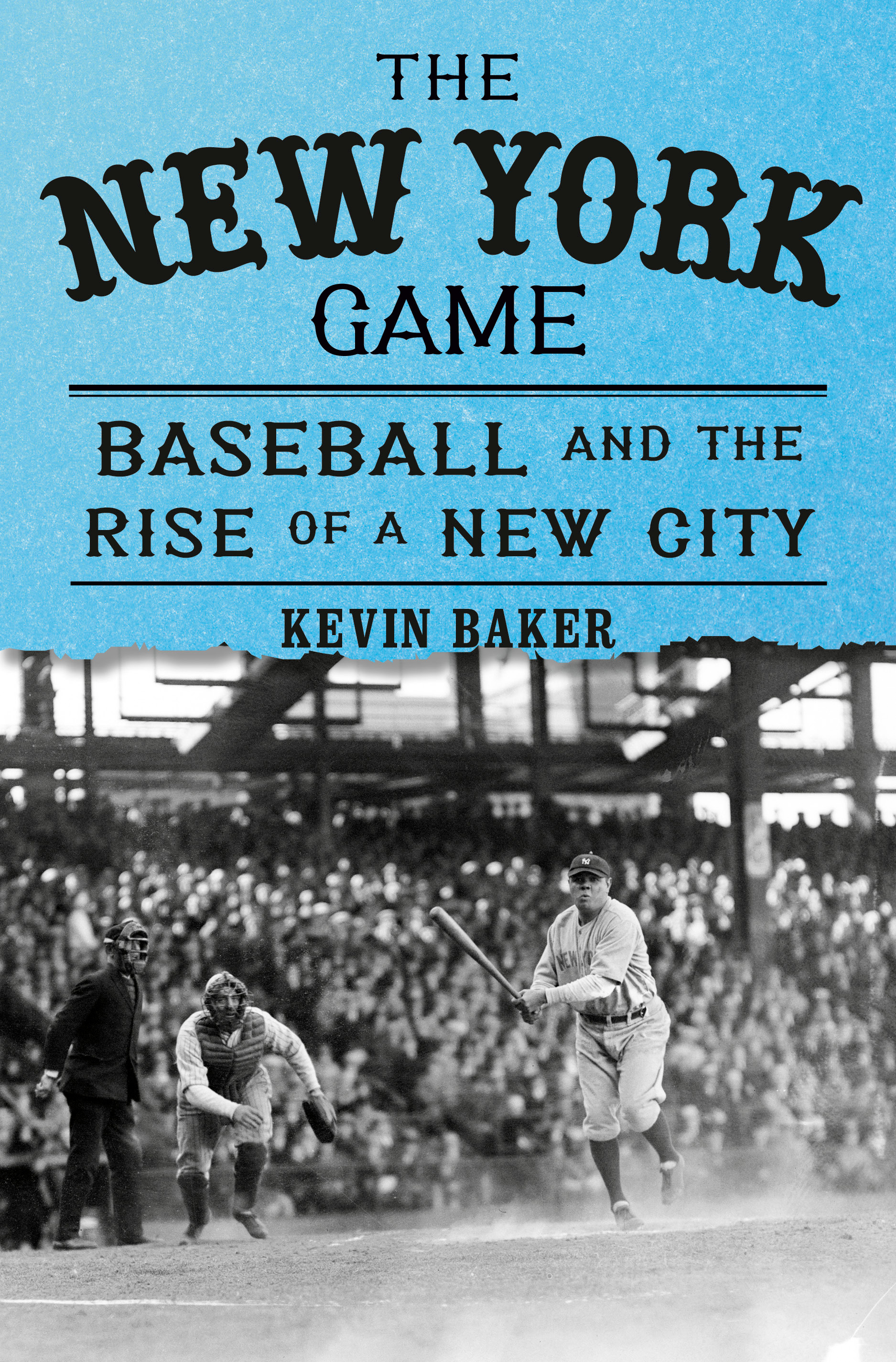

Now the territory of the Mets and Yankees, New York City used to be the home of ballclubs like the Robins, Highlanders, Superbras and Giants. While the Mets and Yanks are covered in his new book The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City, author Kevin Baker also makes sure to tell the stories of all of the lesser-known clubs that took to the diamond in NYC since the game was first played in deserted lots and vacant tavern yards in the 1820s. In this excerpt from The New York Game, Baker, the co-author of Reggie Jackson’s Becoming Mr. October, delves into some of the ballparks that replaced those lots and yards as baseball became a professional endeavor instead of just a pastime. The New York Game hits shelves and warehouses of online booksellers today.

There Used to Be a Ballpark…

New York’s original Penn Station, it is said, was inspired by the Roman Baths of Caracalla, completed 1,808 years ago. Projects to transform today’s Penn Station feel like they have taken about as long.

Strange days for a city that used to throw up the greatest skyscrapers anyone had ever seen in a year or so. Whatever scheme one favors for the area, though — and there are plenty of them — there is one, corporeal fact thwarting any progress. That is the current Madison Square Garden, which squats atop the station like a malevolent toad. Getting rid of the thing, it seems clear, will entail paying off James Dolan to move his teams and his dreary arena elsewhere—no matter the decades of massive rent breaks and other subsidies the public has already bestowed upon the Garden.

The very idea that sports owners would have to be bribed or subsidized would have been inconceivable to New York’s power brokers for most of the city’s history. Rather, it was the teams that were forced to cater to the politicians and the public. Those that didn’t fall into line suffered the consequences. The first ballparks of both the Yankees and the (baseball) Giants, Hilltop Park and the original Polo Grounds, respectively, were abruptly demolished after the city decided to run a street through their grounds. Right up through the construction of Shea Stadium — named for a genial political fixer — the need to play ball with the power establishment shaped the very nature of our teams, where they played and the architecture of their parks.

Even the great tragedy of New York sports, the move of the Giants and the Brooklyn Dodgers to California after the 1957 season, occurred in good part because the city refused to subsidize both teams’ demands for lavish new stadiums. Robert Moses wanted to rent them a new municipal stadium out on what had been the Corona Dump, the site of the mountainous ash heaps immortalized by Fitzgerald in The Great Gatsby. (The dump had been the domain of another famous political fixer, John “Fishhooks” McCarthy, who went to mass every morning to pray: “God, give us health and rest. We’ll steal the rest.”)

The Giants went to San Francisco, the Dodgers went to Los Angeles. Shea Stadium was built on the site of Fishhooks’ old dump, and the Mets were born. Ebbets Field was torn down and Frank Sinatra sang a sad song: “There used to be a ballpark/ Right here…” But the plans the owners had pushed included a West Side Highway ballpark — in New York, bad ideas never die, they just go to the West Side — and the destruction of dozens of blocks of brownstone Brooklyn. The city took a bullet — but dodged an atom bomb. And much as the fans grieved, most people seemed to agree.

“There was simply no significant political support for a public subsidy for a privately owned stadium operated by a profit-making enterprise,” as Henry Fetter pointed out in his illuminating economic history, Taking on the Yankees: Winning and Losing in the Business of Baseball.

The business of New York, public or private, was just not about making its highly profitable sports teams even more profitable. Such entertainments were generally left to the marginal spaces of the city. New York teams routinely played on what only yesterday had been garbage dumps — not to mention swamps, pig sties, industrial waste sites, and even river-bottom land. Far from chasing their owners out of town, it seemed to make them more ingenious.

The Dodgers had begun life in Washington Park, next to the aromatic waters of the Gowanus Canal. Charles Hercules Ebbets and his partners built Ebbets Field on a quaint corner of Flatbush known as “Pigtown,” where local residents tossed their garbage into an enormous pit, for the delectation of the neighboring pig farmers. No public official dreamed of giving them a dime.

Those original Polo Grounds encompassed four blocks just off the northeastern tip of Central Park. John B. Day, a young tobacco dealer from Connecticut, owned two teams there — one from each of the rival major leagues of the 1880s — and fended off the encroaching street grid by providing the Board of Aldermen with free season passes. When the landfill used to level off the field proved to be pure garbage, Day moved his New York Metropolitan club to a new site, between 107th and 109th Street along the East River. It seemed like the perfect location, a scenic, waterfront stadium. Yet Day proved to have an unerring nose for garbage. Metropolitan Park had been built over yet another city dump, and just across the river from Astoria factories that pumped “foul smoke” into the faces of the fans. Met pitcher Jack Lynch claimed that a player might “go down for a grounder, and come up with six months of malaria.”

A few years later, the aldermen finally rammed 111th Street through Day’s ballpark anyway (Did someone not get his tickets?) and he was forced to take his world champion Giants over to the St. George Cricket Club, on Staten Island. The grounds had been used for outdoor theatre the year before, leaving it mostly devoid of grass, and the stage scaffolding had been left behind. Heavy rains rendered the outfield so waterlogged that the Giants were forced to lay down wooden planks for their outfielders to clatter across in pursuit of flyballs. Picture the Yankees today, trying to play in the pond behind Central Park’s Delacorte Theatre.

Rather than demand that the people build his wildly popular team a new ballpark, though, Day located two large lots of land, running along Eighth Avenue below the 155th St. viaduct — land that had, until just 15 years earlier, been literally under the East River. In the space of 17 days, the Giants owner purchased one of the lots, hired a leading ballpark architect, graded the property, hauled the grandstand of the Old Polo Grounds up to Harlem, and built a new Polo Grounds — one that would be torn down, rebuilt, consumed by fire, and rebuilt again into the most gloriously eccentric sports stadium ever constructed. Entirely with the team’s own money.

By this time, though, New York baseball clubs — and especially the Giants — had begun to all but merge with Tammany Hall, the city’s legendary political machine. Politics could be used to keep competition out, as well as enhance it. By the first years of the 20th century, the Giants were run by the irascible Andrew Freedman, later described by Bill James as “George Steinbrenner on Quaaludes, with a touch of Al Capone” and “a thug who skated on thin ice above an ocean of lunacy.” Yet Freedman’s political credentials were impeccable. He sat on Tammany’s powerful policy board and its finance committee—as well as the new Interborough Rapid Transit Committee, then deciding just where the city’s new subway system would run.

As such, Freedman had the power to ruin almost any site where the new, upstart American League tried to acquire. Finally, the AL gave in, handing the franchise rights over to some of the very sleaziest products from the machine. The primary owners of the new team — soon to be known as the “Highlanders” or the “Yankees” — were Frank Farrell, operator of the most extensive gambling network in the country, and enormous, bibulous, walrus-moustached “Big Bill” Devery, who had run for mayor under the novel slogan, “You can trust a thief, but you can’t trust a liar,” and before that had been the most corrupt chief of police in New York history, which was saying something.

“He was no more fit to be chief of police than the fish man was to be director of the Aquarium,” Lincoln Steffens would write, “but as a character, as a work of art, he was a masterpiece.”

Tammany stuck its new team up on Washington Heights, in what was called “Hilltop Park,” but better known as “The Rockpile.” The contractor for the park was Thomas McAvoy, a former police inspector whose main claim to virtue was that he never took “whore money.” His handiwork was yet another homage to landfill, but by Opening Day, April 30, 1903, The Rockpile remained — to be charitable — “incomplete.” There was no clubhouse yet, and both teams had to change in a nearby hotel. Neither the roof nor the bleachers were finished, and the sun reflected so brightly off the baked earth and rocks of McAvoy’s field that fans complained they were blinded by the glare. In right field was a gaping crater, referred to as a “hollow.” The Highlanders would try to cover the hollow with wooden planks, then resorted to having spectators stand in it.

Ten years on, the Yankees were, not surprisingly, a disaster. Sportswriters liked to refer to them as the “jinxed” or “bad-luck” team of baseball, but that luck may have had a little something to do with management. Devery and Farrell, dead broke, were forced to sell the team, and the Streets Department came for Hilltop Park, as it comes for us all in the end. The Rockpile became Columbia-Presbyterian, then the first academic medical center in the world. The Yankees were forced to move in with the Giants at the Polo Grounds, paying the then not-inconsiderable rent of $65,000 a year.

How World War I Led to the Creation of the NFL

We talked to Chicago sportswriter Chris Serb about his book “War Football: World War I and the Birth of the NFL”Their new owners were a pair of colonels who had never fought a battle. One was a civil engineer with the unlikely name of Tillinghast L’Hommideau Huston; the other a silver-spoon dandy named Jacob Ruppert. Ruppert seemed like one more character, a nepo baby who had inherited his father’s brewery and East Side mansion. Though born in Manhattan, he spoke with a heavy German accent, and liked to collect yachts, thoroughbreds, purebred dogs, exotic animals, jade and porcelain, rare first editions, and very discreet mistresses.

Yet the funny little colonel with the Old World accent also had a diamond-edged mind. He would prove to be perhaps the greatest sports owner in American history, the one man who, more than any other, would begin the corporatization of professional sports, and its move away from the control of the politicians and the public. He did it by starting out within the machine.

At 21, Jake Ruppert joined not only his father’s brewery business, but also Tammany Hall. Before long, Ruppert’s Knickerbocker beer was featured in Tammany saloons all over New York. In return, young Jake served four terms in Congress from the East Side’s “Silk Stocking District,” in order to secure the German vote. Moving on to the Yankees, he proved to be relentless, even pitiless in his ambitions, wresting control of the team from his fellow “colonel,” driving the president and creator of the American League, Ban Johnson, out of baseball — and buying up Babe Ruth from the Red Sox.

The Giants decided they had a problem on their hands. With Sunday baseball newly legal in New York, they begrudged handing over half of their Sabbath dates — always the biggest attendance days, especially before night baseball — to their tenants. Before the Babe was two months into his first season in New York, the Giants canceled their lease. After the 1920 season, the Yankees would have to go — preferably out of town.

It was an old-school Tammany move but the Giants ownership — now thoroughly dominated by machine hacks — did not understand how the game, and the city, were changing. Ruppert was at least three moves ahead of them. His own Tammany credentials were impeccable, and his fellow owners were not about to let the sport’s greatest attraction be detached from the nation’s leading media market. Just in case they were, Ruppert, still in the midst of stripping the Red Sox of their best players, had secured the lease on Fenway Park. (The Boston Yankees? The mind boggles.)

The Yankees were not about to go quietly to an outdoor theatre in Staten Island, or a garbage dump along the East River. The Giants were forced to let them stay in the Polo Grounds for another two seasons, until Ruppert was able to find an abandoned lumberyard in the Bronx and fill it with a huge new ballpark — really a stadium — far beyond the capacity or the splendor of any existing baseball venue.

The Giants still thought they had won. Manager John McGraw, thinking of the bucolic, backwoods Bronx of the recent past, crowed that “They are going to Goatville, and soon they will be lost sight of.” He was wrong. The subway was rapidly turning the Bronx into what the papers were calling, “the wonder borough,” an upper-middle-class heaven where all the strivers from Manhattan’s slums aspired to — the city of the future.

“The Yankee Stadium is a mistake,” Jacob Ruppert would say a few years later. “Not mine, but the Giants’.”

Pro sports had become big business…

From The New York Game: Baseball and the Rise of a New City by Kevin Baker. Reprinted by permission of Alfred A. Knopf, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. Copyright © 2024 by Kevin Baker.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.