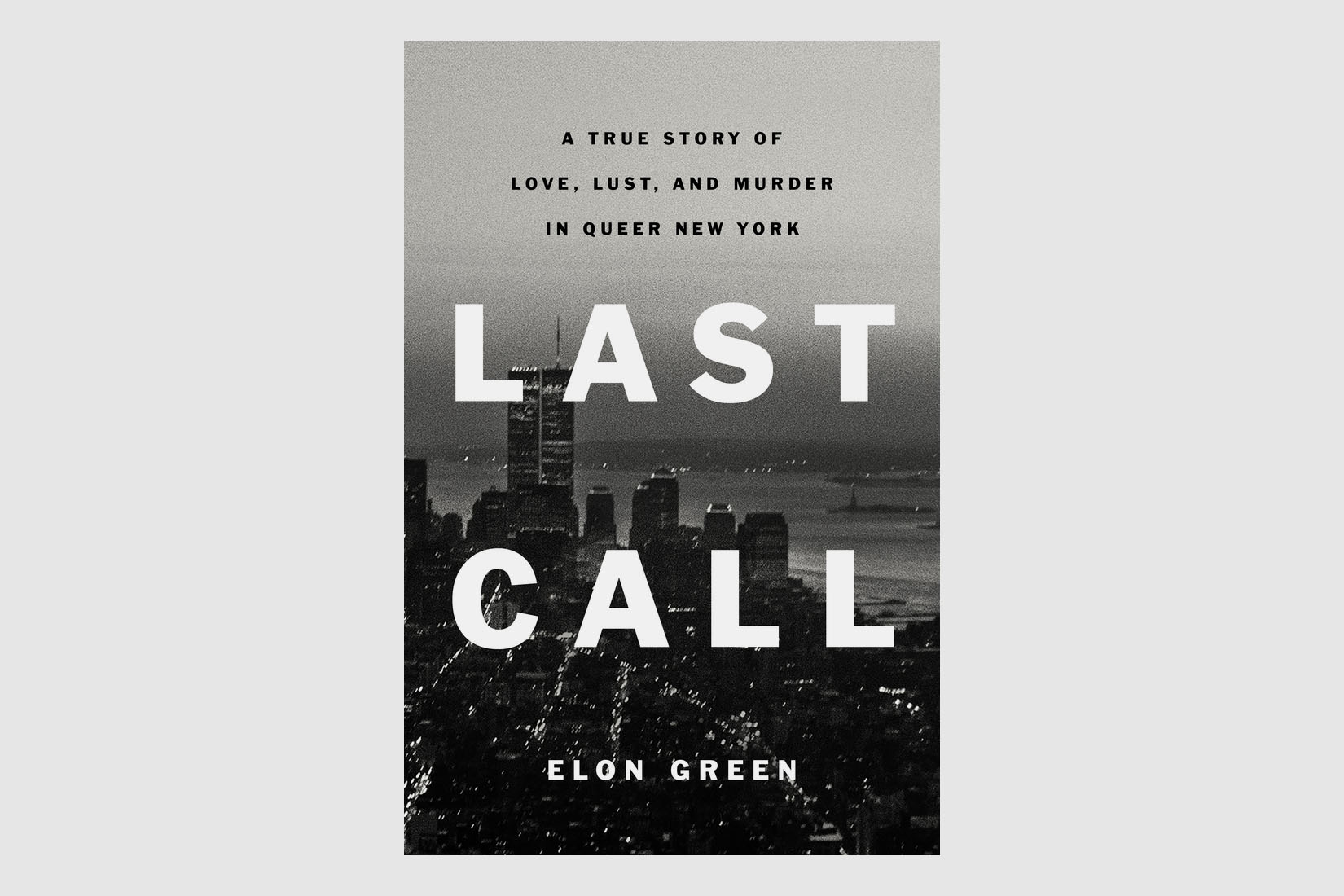

A number of true crime narratives in recent years have turned their focus on forgotten or overlooked cases, with gripping results. Far fewer, however, have applied lessons from a Pulitzer Prize-winning novel published almost a century ago. There’s a lot to like about about Elon Green’s gripping, haunting new book Last Call: A True Story of Love, Lust, and Murder in Queer New York — but one of the most fascinating things about it is its unlikely literary influence.

To be more specific, Green drew inspiration for Last Call from Thornton Wilder’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1927 novel The Bridge of San Luis Rey. That novel focused on the aftermath of a fatal bridge collapse to tell the life stories of those who died in the accident. In the case of this book, that meant taking an approach that emphasized the lives of the men who were murdered, rather than on the mysterious figure who came to be known as the Last Call Killer.

For Green, the appeal of this approach centered around, in his words, “the whole idea of trying to figure out how these men had all arrived in that one place, and what their past was.”

“I was using that very idea in my meetings with editors and with publishers. That was always the point,” he tells InsideHook. “The focus of these chapters were always these guys.”

Last Call opens in 1991 with a seemingly innocuous scene: a maintenance worker cleaning up garbage at a Pennsylvania Turnpike rest area. Soon, he finds a number of garbage bags that seem far heavier than they should be. That sense of something being very wrong increases until the worker catches sight of freckles within one of the bags. Cue the police, who realize that they have a crime scene on their hands.

Over the course of the next few years, more bodies show up in a similar condition. Research into the victims’ histories slowly leads to an inexorable conclusion: there’s a serial killer targeting gay men in the Northeast. In 1993, reporter Mike McAlary dubbed the perpetrator the “Last Call Killer,” and excoriated various New York City institutions for not taking the threat he posed seriously.

The search for the killer spanned multiple jurisdictions and eventually led to the formation of a task force consisting of police from numerous states. But, just as Green opted against going in an obvious direction by focusing on the killer’s victims, he made a similar decision when it came to the role law enforcement played in the narrative.

“From the beginning, I was very conscious of how I portrayed the police in the book and how I used the information that I was given from the police,” Green says. “I interviewed all of them multiple times, and largely it was both to try to verify other sources of information and to settle inconsistencies.”

“The way I hope it comes across — the whole point of the way I wrote about it — was to use the investigation to just write about the men,” he added. “So I viewed the detectives as the means to that end.”

Structurally, the way the investigation unfolded — which ultimately connected it to a killing decades earlier in Maine — dovetailed with Green’s thematic concerns. “I tried to make sure that there are no detective heroes in the book, and it wasn’t that hard to do, because there are no detective heroes in the story,” he says. “Ultimately the case does get solved, but it’s because of an industrious fingerprint examiner in Maine and also the man or woman who took the fingerprints in 1973. All the other detective work — a lot of which was excellent — didn’t really matter in the end when it came to identifying the murderer.”

To read Green’s book is to take in a moving portrait of a group of men whose lives ended far too early — and to explore the collateral damage to the spaces frequented by the killer. This included the Townhouse, a piano bar at which Andrew Cunanan — the mid-’90s serial killer whose victims included Gianni Versace — was also, for a brief time, a regular. “The reason I put that in there was to say, the Townhouse couldn’t catch a break,” Green says.

Green used a host of methods to explore the recent past, from police records to conversations with people who were present in the spaces frequented by the Last Call Killer. (One of the interviewees, Townhouse piano player Rick Unterberg, died as a result of COVID-19 shortly before the book went to press.) It’s a wide-ranging ethos that resulted in a gripping yet empathic work of nonfiction.

The way in which Green explored the history of Peter Anderson, the man whose body was found in Pennsylvania, gives a sense of Green’s overall approach. “In the case of Peter, I had been given handwritten case notes, like 50 or 60 pages worth. I had the names of everybody that the police talked to in their investigation, and that was a road map to figure out who he was,” he recalls. In the case of Thomas Mulcahy, another man targeted by the killer, Green took a similar approach. “He went to a prestigious high school in Boston, and because he had been murdered, people remembered him. I talked to eight or nine of his classmates who were, at that point, in their 80s.”

That led to Green noting one of the more bitterly ironic aspects of writing about a case like this. “One of the things about writing about people who have been murdered is, even if they’re not famous, the murder makes them notable in the minds of people who knew them,” he says. “And so they’re liable to remember them better than they would otherwise.”

In Last Call, Green offers a few possible answers for why this case isn’t better-known, from the fact that the killer was targeting gay men to the way his eventual arrest was overshadowed by the September 11 attacks. Green also points out that true-crime narratives — and exposing the horrors of serial killers — did not always enjoy the vogue that has attended it in recent years.

“To give you a sense of what things may have been like with this story in 2001, somewhat more than a decade later, I was working on a story about a case in San Francisco called the Doodler murders — an unsolved case that is now the subject of one of the most popular podcasts in the country,” he recalled. “And when I was pitching that story, it was the most rejected story I’d ever had.”

When it comes to the story of the Last Call Killer, Green does feel that the narrative offers its own challenges. “I think it’s also a complicated story,” he says. “I honestly think that it was hard for people to wrap their head around. It’s hard for me to wrap my head around it.”

In the end, though, Green has accomplished a work that succeeds on multiple levels — of telling the story of the lives cut short by a killer and of offering a gripping account of the way that killer was sought out.

“I tried to be more of a conduit than anything else,” Green said. “It’s a work of history and I always viewed the crimes as a means to tell it. The men are that history; the men are walking through that history.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.