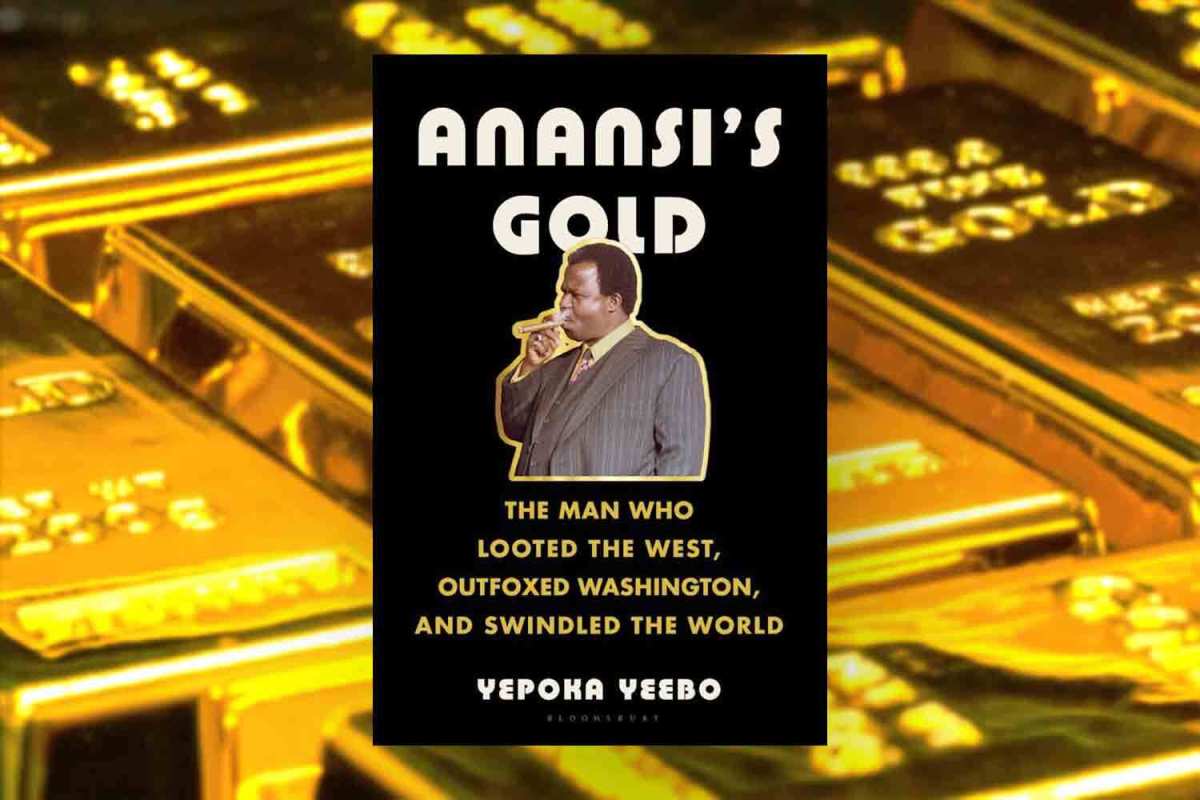

It’s a con as old as time: someone comes to you with a compelling story — that they have access to a fortune secreted away from prying eyes, and if you invest in their project, you’ll end up making your investment back many times over. An especially complex version of this scheme is at the heart of journalist Yepoka Yeebo’s new book Anansi’s Gold: The Man Who Looted the West, Outfoxed Washington, and Swindled the World.

At the center of the book is John Ackay Blay-Miezah, a charismatic figure who rose from humble beginnings in Ghana and used his intelligence and charm to swindle countless people around the world. Blay-Miezah’s con was simple: he argued that Ghana’s former president had secreted away untold riches in the form of a trove of gold.

His pitch to investors was simple: pay him and you could help transform Ghana into a prosperous nation — and make a tidy profit on the side. And as Yeebo recounts, a lot of people — many of whom had genuinely good intentions — were taken in. Anansi’s Gold is an immersive, thrilling read — and a kind of secret history of the second half of the 20th century. InsideHook spoke with Yeebo about the process of writing the book — and her deep connection to the history she wrote about.

InsideHook: How did you first become aware of John Ackay Blay-Miezah’s story — and what piqued your interest to the point of writing a book about him?

Yepoka Yeebo: I got a WhatsApp message from my mum. It was an election year in Ghana, and lots of parties were thrown off the ballot for irregularities. People were talking about whether this was legal, what the precedent was, that kind of thing. And one of the biggest cases people could remember was John Ackay Blay-Miezah’s party being thrown off the ballot. People started sending clips around of his 60 Minutes appearance and discussing not just his party getting thrown off the ballot, but also whether his claims were legitimate.

The thing that surprised me about this WhatsApp message is that my mum asked, “What do you think of what he says?” My mum would always send me outlandish WhatsApps, just to gauge what I thought about them. Or I’d go off and research what they were talking about, and then rant back at her.

I was surprised, because my mum is a serious person. She’s a doctor. She’s very conservative in her views. So it seemed weird that she would think that there was some validity to these claims. And I was kind of obsessed with it, and I showed it to lots of friends, and friends of friends. They all had stories about either huge sums of money going missing, or huge sums of money being reclaimed from politicians. Someone told me about an Indian politician who had actual cash stashed in his walls.

A business journalist friend told me that the Nigerian government was actively reclaiming money stolen by officials and stashed in Swiss banks, successfully. And the weirdest story was that back in Carmel, California, my partner’s dad grew up with a friend whose dad was a news anchor. I guess he was just trying to evade taxes and not pay the IRS. So he just stashed all their money somewhere, and didn’t tell anyone where, and then he died suddenly. The money had evaporated into thin air.

I feel like the very current edition of that are the people who invested a lot of money in cryptocurrency and then forgot their passcodes, and theoretically had hundreds of millions of dollars, but…

However complex things get, it’s always surprisingly easy to lose shocking sums of money. Which I suppose is kind of the reason why John Ackay Blay-Miezah was able to convince so many people that there was this huge amount of money just being stashed away. Because it happened all the time.

Anansi’s Gold was a fascinating book to read, because beyond the con-artist narrative, it’s also a book where the history overlaps with the sort of post-colonial period in the 20th century, with Cold War politics thrown into the mix. Did you have a sense that the scope was going to be so vast when you set out to write it?

I did not. I thought I was writing a caper, and I thought it was going to be fun and lighthearted — “He took money from rich people. Isn’t that cool?” I think probably once I started going through the diplomatic cables in earnest, and realizing that Blay-Miezah was very good at manipulating political events and using them to his advantage. Whenever there was a slight change of government, that would be an excuse for investors not getting their money.

He also liked to engineer political crises. He loved throwing a press conference to distract people from whatever was happening next. So then I had to read up on the context of what was happening in the country at the time, just to get a sense of why he was playing certain people against each other.

It got to the point where I was writing around his election campaign, and then the trial. And I realized how politically connected all the players were, even minor people who came to give evidence. It was weird how plugged into Ghana’s power structure he was, and how good he was at ingratiating himself and using people’s reputations as cover. And that got especially dark in the 1980s, because he was propping up one hell of a murderous dictator.

There’s definitely that shift where, as you said, the caper part of it turns into something much bleaker, where he’s dealing with this terrible regime. I think there are people who were Nazi-adjacent who he began working with as well. What do you think it was about him that he was able to kind of survive so many shifts in governments within Ghana, and was able to endure where so many other people had fallen out of favor, or were being imprisoned?

I think part of it was just that he was incredibly intelligent, and a quick study, and very good at mimicking people, and people around him, and people’s status. I used to ask people this question all the time: “How did he keep getting away with it?”

They told me, it’s hard to see now, but at the time, people who had been politicians who were honest, who were not actively grafting, or even just making connections, they were civil servants. So they had to go back to their previous jobs, or make a living, and had to survive. And a lot of what Blay-Miezah gave them was access to money and other people.

But on top of that, he was just really clever at using whatever was happening to his advantage.

And I think he was also pretty shameless about continuing to try to get away with it. He would promise literally anything, he would convince people who were sent to investigate him that he had a point, and [then] they were behind him.

At one point, I went to interview somebody who had been a police officer who was sent to carry Blay-Miezah’s diplomatic passport, so he couldn’t misuse it. He was lovely, and when I was in his office, I noticed that there was, like, a globe up in a corner, on the very top of a bookcase. And then there was a framed photo of Blay-Miezah next to it.

When I talked to a source who had been in intelligence at the time, he said that this person had basically been sent to London, gone AWOL, and then the next time they saw him, it was on 60 Minutes, and he was being described as a police officer working for Blay-Miezah. He did this in the U.K., he did this to investigators in the States — he just charmed his way out of everything by promising people exactly what they wanted. I think maybe he knew more than most people what people wanted.

As you wrote, Blay-Miezah really had this idea from a very early age — when he wasn’t even 20, he had been able to set himself up as a healer and had all of these people devoted to him. He was able to project this image of absurd success, even at the earliest possible stage that he could.

I just remember one of the British investigators I talked to saying, “Blay-Miezah was said to be able to put the evil eye on people. And I’m pretty sure he did it to me.” I don’t believe in that stuff, but I got a chill. It’s kind of extraordinary. I also think he always looked and played the part. I think that was a huge part of everything as well.

Was it difficult finding people who had interacted with him who were willing to talk on the record? Were there still a fair number of people out there from the different groups that he had spoken to over the years?

There were. Because I was writing this over the course of six years, a lot of them were older and a lot of them passed away as we were playing phone tag or setting up interviews or I was getting messages to them, which was deeply sad. It’s always frustrating when the last person who could possibly know about this corner of a story is gone.

I always say, if I could do one thing, it would be to force people to make recordings about their lives and have them sealed. I think this was actually part of the Northern Ireland peace process. Once they die, those become available publicly, so all the incredible stuff that only they know will be known.

There was a lot of that, which was really difficult. And I lost my grandfather around that time as well, so I felt that really keenly. But there were lots of people who preferred to stay off the record for various reasons. I think some people were still deeply embarrassed that they had been taken in by this. Some people still believe, but they just didn’t want to be associated with it anymore. Some people had lost their family and their homes and their property and had had to rebuild their lives afterwards, and they just didn’t want to talk about it in great depth. And then there were people who were happy to chat. Some of them thought that Blay-Miezah was an absolute crook, but the stories were true.

I mean, as you were writing this, there were a few very sympathetic people who ended up being taken in by Blay-Miezah. You talk about the head of Tata Brewing, who has done this very admirable thing in creating a locally owned business and a brewery and was taken in and lost everything as a result of it. There was also a priest based in Philadelphia who had been very involved in the civil rights movement. It’s heartbreaking to read that.

If anyone should have ended up in the scheme where the money did actually materialize, it should have been people like James Edward Woodruff and J.K. Siaw who worked and believed and put a great deal of their lives behind building things. It broke my heart every single time I learned more about either of them.

I got the sense towards the end from tapes and statements that Blay-Miezah wanted all the things he had promised people to come true and was actively trying to make that possible, as ridiculous as that sounds and as complex as that would have been. He was, for a while, convinced that if he became president he could at least give people contracts or pay them off in one way or another and give them what they were owed that way.

There are lots of people who got caught up in this, and while everybody was to a certain extent being greedy — how could money meant for a nation be randomly distributed privately by a random guy? — they also wanted to build great things or restore communities and build unity between two different Black parts of the world. They were excited about building monorails and ports and plants. And, yeah, it is sad that all of that came to naught, because a lot of it would have been remarkable.

I think you used the phrase “too big to fail” at one point to refer to the size of this sort of con. Were there other accounts of cons or Ponzi schemes or just financial misdeeds in general that you saw parallels with?

Crypto is the obvious one, because so many people so successfully scammed people by exploiting the complexities of the way crypto works and the fact that people didn’t really need to know much about it to want to make money from it. Which is kind of exactly what was happening with Blay-Miezah’s investors outside of Ghana.

The whole leveraging political power and running for president stuff has some very obvious parallels. Because I started in 2016, that wasn’t where I thought it was going to go. And then it went there.

There’s one more thing I was just thinking about where I thought: that’s creepy. At the heart of it is the way that a lot of people would like something for nothing and are willing to back absolutely insane premises to get anywhere near that. A few years ago, there was a scam in Ghana where a guy was selling either gold bars or shares of gold bars, except it turned out he didn’t have any gold at all. But by that point, thousands of people had invested and lost everything.

When people describe a business thing and you think: that’s too complicated to work or that’s quite clearly going to be a Ponzi scheme or like a multi-level marketing thing, it was one of those things where you’re thinking, “But where did this guy get all the gold?” What special business and industrial access does he have that no one else does? The fool’s gold was no longer fool’s gold; it became gold.

Did a Cult Hide in Plain Sight for Several Decades in New York City?

Alexander Stille, author of “The Sullivanians,” on secret histories, therapeutic turf wars and what makes something a cultDid researching and writing this book change the way anything that you had thought about the 20th century history of Ghana?

Yes, to an astonishing degree. Early on when I saw a name come up, I’d want to research this person and how they intersected with the story. I’d go and pull everything I could find at like a British library or I’d search through academic databases and there’d be like a fairly healthy dose of secondary stuff, but not nearly enough to answer any of the questions that I had.

So I was looking for biographical information on Ignatius Kutu Acheampong, for example, who was a leader during the 1970s. There should be plenty there, and there just wasn’t. I ended up having to go to primary sources repeatedly. It got really frustrating, because it just doesn’t make sense that for an established country with a fairly well-known history there wasn’t much secondary literature.

It got really frustrating also because with primary stuff, you have to crawl through it to find stuff. When you’re looking at microfilm it is painful, but then it just started to get really cool and really fun, because you’re thumbing through newspapers, you’re seeing all the side stories. This is what people wore, this is what people did to go out, this is what they were into. This is what the economy was like — all these stories of people’s lives that I wouldn’t have encountered if I didn’t have to stare at newspapers.

At one point I was at Temple, and the Philadelphia Evening Bulletin had donated their archives to the library there. As well as microfilm, there was just their morgue, where people had clipped the clips and put them in alphabetical order. I picked up one of the clips and it was from 1912. And I thought, “Should I be touching this?” And then I started to get really obsessed with all those fascinating details that you can really find from primary sources.

But again, it was time-consuming, expensive. I got lucky in that I had access to academic databases, which not everybody does; they are incredibly expensive on top of everything. It just really frustrated me, because that lack of material meant that people could say anything and it would be really hard to refute even the most outlandish claims. And this is literally how Blay-Miezah did as well as he did. You make history inaccessible. You make evidence inaccessible. And then you could lie to anyone.

That was really frustrating, especially in the ’80s, because it just coincided with my family history. And I saw the very real effects of that. And it was devastating.

How did your family’s history coincide with the scope of the book?

So both my parents were in political organizations between 1979 and 1981. And my dad was actually a politician under Jerry John Rawlings very, very briefly until Rawlings attempted to assassinate him multiple times.

Oh my god.

Yeah. And so while I was working on the early-’80s portion of the book, Jerry Rawlings actually died.

It’s the usual thing on social media, where people have lots to say when somebody this polarizing dies. But what surprised me was that members of my own family had lovely things to say about Rawlings. Absolutely glowing, especially the younger ones. And so at one point, it was giving me a headache. I had to ask one of my cousins — I called her or texted her — “Do you not know why we couldn’t come back to Ghana?” And she didn’t. Her parents had not told her that my father was in exile, and my mom had to just leave the country.

This is my own family — information that everybody had, that had defined my whole life. It’s why I’m in Britain. It’s why I could not go back to Ghana for a very long time. It’s why I didn’t meet my cousins or my grandparents until way later. The time I had with these people was like, stolen from me and my sister and my mom and my dad.

I remember this was right before it got really dark, I was just chatting to my mom about what it was like.

And she said, ”I’m a women’s organizer.” So they’d go out into the countryside and talk to people about running for office, voting, capacity building, that kind of stuff. She said they’d meet up in Accra, and then everybody would disperse. And then slowly, like, her friends stopped coming back. They just started to disappear.

Then she started to weep, and I realized that she hadn’t even thought about that for a very, very long time.

So the idea that all this had happened, and had like, basically defined my life — and my own cousins, who I love dearly, and who are very well-informed and very highly educated, were not aware of this — was infuriating.

I noticed how thoroughly Rawlings had laundered his reputation when I was looking through Getty Images. There were pictures of him with Michael Jackson, and Bill and Hillary Clinton. He ran this whole reputation-laundering operation that was flawless, exquisitely, exquisitely executed. And he used it to cover up the fact that he and his family just robbed the country the entire time, appropriated state-owned companies and assets, hand over fist.

Once, a source told me a story. Rawlings had a really large house in a very central part of Accra. Next to it was an empty lot that was an old colonial era building. And those were slowly being sorted through by the land commission, who would then go and sell them. But it was dilapidated, it was on an acre. So when he was in training, he moved into it and squatted it and took care of it. And Rawlings’s house was right next door. And then, the source got posted elsewhere and went away.

When he went back to visit a friend, he couldn’t find the entrance to where he had been staying, only Rawlings’s house. And it took him walking around the block a couple of times to realize that Rawlings had just had a wall built around the adjoining acre that perfectly matched the walls of his house. It’s like the land disappeared, and nobody had anything to stop it. This was recent, too.

It was just a mindfuck to see how something as simple as me not being able to look up a pretty recently written biography of General Acheampong just screwed both history, but also was fucking up the current day. Because this man has so thoroughly laundered his reputation, and people were letting him literally steal land. It’s criminal.

I like having arguments. The happiest moment I’ve had since this book came out — and I’ve been fortunate, there have been plenty — was that I saw people in Ghana… The economy is for shit, and there’s an election coming up. And people were saying, ”It’s time for another coup, get these people out.”

And so a lot of people responded, “Do you not know what happens during a coup?” I saw someone making this argument. And then I saw that he had little sections from like an ebook to back up his argument, and I clicked on the picture and the reference was me. He didn’t reference me, but it was my book. And I thought, “Yes, that’s all I want. I wanted you to be able to find people on the internet, with the information I was able to make readily available. That’s all I wanted.”

In Anansi’s Gold, you mention that a 60 Minutes report from the late 80s really was kind of the one time Blay-Miezah’s work was put into the spotlight. Have there been any tangible reactions from people since the book has been published?

Yes and no. I feel like it’s early days yet. I’ve not been back to Ghana since and Ghana is where I’d really hear it from people. People have been lovely. Lots of people have been super-friendly and argumentative about my details — or the idea that I would write about like a criminal at all. Which I fully understand. There are lots of way better, way more deserving, honorable guardians to write about. But crime is entertaining to me.

I was really only worried, at least when I was writing about the reactions I’d get from people like Rawlings or Jewel Ackah. And it was insane that they passed away. A lot of people from that era passed away before my book was published. I’m sure I will hear from people in more detail, especially from Ghana. I know it’s controversial. I found a lot of stuff that contradicts prevailing narratives about historical events. I make beloved people look a lot less like they deserve to be beloved people. It’s a text, it’s full of information. There’s lots there and there’s lots for people to argue about. And that’s kind of the fun of it as well.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.