The right vocalist can make a good song great and a great song transcendental. Every vocalist is different, and every vocalist’s voice is an instrument that evolves over time; listen to Bob Dylan singing in 1964 and 2024 and you’ll get a fascinating lesson in what time and craft can do to a singular approach to singing.

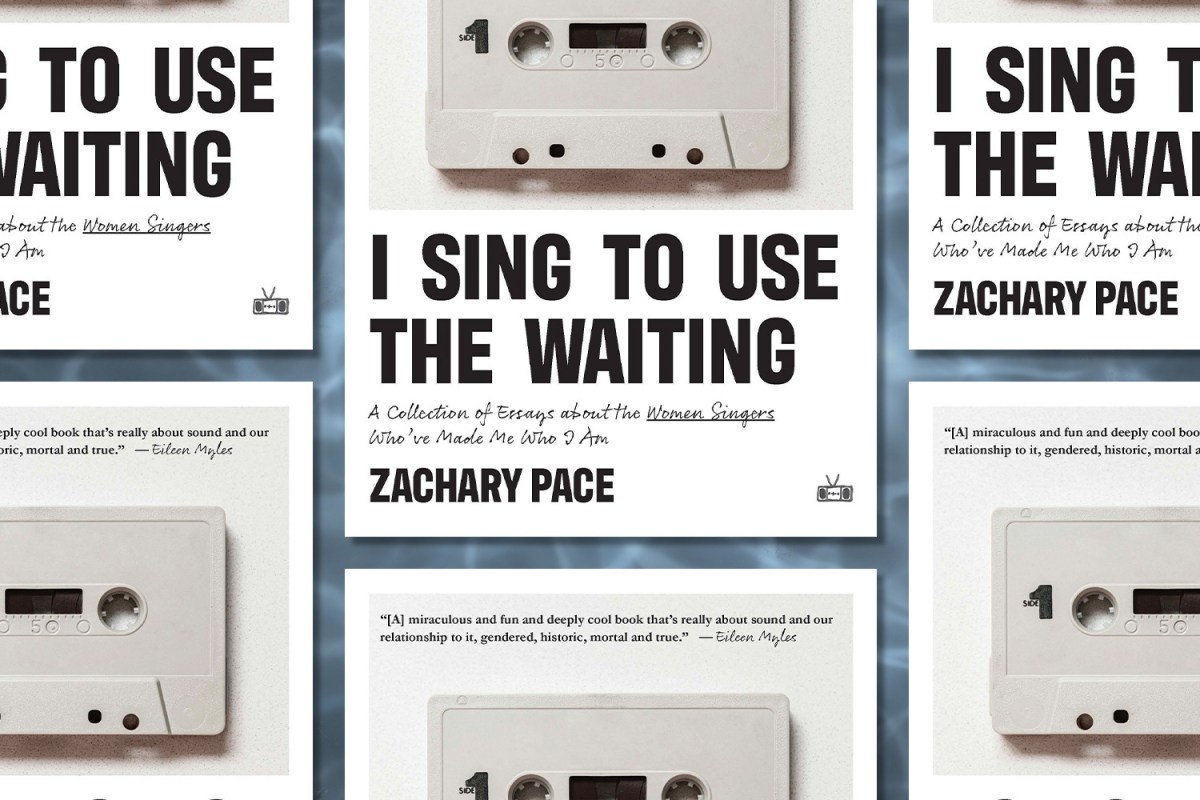

But vocals can also reveal plenty about the person listening to a song. It’s a question that Zachary Pace takes up in their new essay collection I Sing to Use the Waiting: A Collection of Essays about the Women Singers Who’ve Made Me Who I Am. Pace’s book weaves their own personal history into precisely written considerations of musicians like Chan Marshall of Cat Power, Whitney Houston and Cher.

InsideHook talked to Pace about their new book, the wide-ranging approach they took to writing it and everything from growing up in Cooperstown to the role of bootleg recordings in better understanding your favorite artists.

InsideHook: At what point did the idea of the book click into place for you? Did you always think of these essays as part of a larger project, or was there a moment when you realized that you’d been writing a lot on a specific theme and could turn that into something bigger?

Zachary Pace: It was the second way. I had written four of them, but at the fourth one I realized that I wanted to and could keep going with them. I wrote the Cat Power essay first, Kim Gordon second and Madonna third. Then, when writing the piece on the queer voice, that’s when I encountered this quote from the documentary Do I Sound Gay? from the speech-language-hearing expert Benjamin Munson. He talks about how a child chooses a role model early in life and that’s how, in large part, a voice and a personality is formed. That one piece of information turned the lightbulb on and I thought, “I can think of so many different women singers and performers whose personalities are a part of mine.” That’s how I decided to keep going — but there were four isolated incidents before that.

A lot of the artists you wrote about in I Sing to Use the Waiting are people who have had vast careers. The Kim Gordon and Madonna and Whitney Houston essays all take on several decades in their lives, but other essays focus on artists who haven’t been at it as long, like Hop Along. Was it challenging to figure out what aspects of a certain artist to focus on?

After those first four pieces, when I decided that I’d like to build it out into a book, I chose four more subjects. I did have an idea for what aspect of their career I was most interested in. For example, with Cher, I knew that those two films were going to be the most important time and in her career that I’d want to focus on — but the first draft of that was from birth to now, and it was three times as long as it turned out. I centered the essay on those films, but I couldn’t help but bring in everything that I had learned from her birth to her current career.

It took a long time, for that one in particular and for several of them, for their main point to surface. There was a lot of excess detail for such a long time because everything seemed relevant and important and interesting to me. It took a really long time to narrow it down to what was actually the most important point. That created eight essays, which was the original draft of the manuscript — and now there are 14.

I would think about new possible essays more in terms of the turning-point moment in the career of the artist than just wanting to approach the artist in general. From those original eight I learned that I couldn’t try and write biographies. I had to stay really close to a certain turning point moment in order for the most important information to come across.

When writing these essays, did you uncover things you hadn’t been aware of when you set out to write them? Did you find that it changed your relationship to some of the music that you were writing about?

Going in to the essay about Hop Along, I wanted to to think about how I encountered that music as a college student and the performer was a female-identified person. We thought of them and spoke of them as “she” and “her.” Now, I was re-encountering the music that I missed over a period of not listening. And Frances [Quinlan], the lead singer of Hop Along, is now identifying through gender-neutral pronouns.

The whole research question there was, “How do I encounter this music now knowing that this person does not identify as a woman singer, a female singer, as the rest of the artists in the book do?” A big part of the appeal when I first encountered Hop Along was the fact that Frances was a female-identified solo guitarist just kicking ass all the time.

And then both Frances and I, in 2021, started to identify through gender-neutral pronouns. So here I am reconceiving of the way I think and speak and hear myself at the same time that I’m re-encountering Frances’s music and trying to describe it and them through not only gender-neutral pronouns, but gender-neutral descriptors. Trying to think of the sound and ways to describe the sound without gendering it.

One aspect of Cher’s music that I think about now after having written about her is that she’s spoken about how her voice sounds masculine and she doesn’t like her voice. I didn’t actually know that until after the essay had been written and that detail wasn’t a part of the story. I do regret not being able to work it in somehow because it’s so relevant to the project.

One of the overarching themes of the book is my dislike of my voice — and even now I can hear myself modulating it because I’m talking to a stranger. In any case that’s something I think about when I hear Cher’s music now — how I know that she doesn’t like her own voice because it’s not feminine enough for her.

There’s a Q&A at the end of the book in which you mentioned that you’re working on a book about Alice Coltrane; I’d love to know more about that.

Well, I would like to. I thought that would be the next thing, but something else has come into place, which I don’t think I can talk about at the moment. But I would like to write about Alice Coltrane. I submitted a proposal for a 33 1/3 on A Monastic Trio, her first solo album, and then I submitted a proposal to the University of Texas Press for Why Alice Coltrane Matters. They didn’t go for it. So I’d like to go rogue and just write something about Alice Coltrane that doesn’t fit into a series.

The cover art for I Sing to Use the Waiting has a cassette on it and, for a lot of the artists you’re writing about, you’re not just writing about official albums and singles, but you’re also covering bootleg recordings and performance footage that has made its way to YouTube. How do you think having all of that out in the world can affect someone’s understanding of an artist? And how did you decide what you were and were not going to use when so much of that is now available?

I think my interest in that — I want to say subculture, but I think sub-career works in some ways — began in my youth. A lot of it was in opposition to a prohibition of some kind when I was a kid.

We didn’t have computers and internet in the house; it wasn’t even conceivable at a certain point. I grew up in upstate New York, and there’s still this palpable feeling of being cut off from things that are available because we’re in this remote rural setting and, to this day, the internet kind of sucks, so it’s hard to access certain media. When I got to college and we had ethernet in the dorms, you could access the music libraries of everybody in the building and instantly download hundreds of files. That’s where I got my first exposure to Cat Power and Nina Simone, and dozens and dozens of musicians I encountered there through being able to just drop these files into my computer.

That’s where I started to encounter rare recordings and alternate versions of things. I think because I was so thrilled by that accessibility and because it was so liberating compared to this feeling of being cut off from what was available, I just became obsessed with collecting rare, hard-to-find and unknown recordings.

I hope I’m not misremembering this from reading your book, but you’re an only child, right?

Yeah, that’s right.

I am, too, and reading your book brought back a lot of memories of having to find music in fits and starts, as opposed to having an older sibling who pointed me in the direction of something interesting. And I think that trial-and-error method has had a big impact on my own relationship with music.

You’re making me think of something I’ve never really told anybody about. Growing up my tastes were pretty mainstream for a young queer kid. But when I got to college and started encountering all of this music that was instantly available to download — I went to college with Kim Gordon’s niece. I didn’t I didn’t know Sonic Youth at the time, but I knew Kim’s niece and we were friends. I thought she was the most beautiful, cool, sophisticated hip person I’d ever met in my life. She really liked Cat Power, and I got into her musical taste.

Also this guy I was dating while I was there, he really liked a lot of artists like Portishead. I started to get into music because of the people who I was attracted to at school. I just wanted to emulate them and I thought we had a lot in common. I sort of came into my style, my aesthetics, by identifying what I liked about these people, and one of them just happened to be Kim’s niece and we’re still friends to this day.

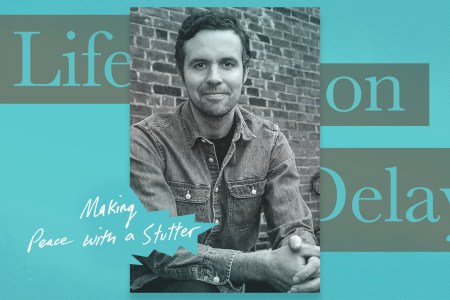

This Journalist’s Memoir Chronicles Living and Working With a Stutter

An interview with John Hendrickson, author of “Life on Delay”In your book, you wrote about growing up in Cooperstown, New York — which I really only know from having gone to the Baseball Hall of Fame when I was 12 years old. And I’m curious — what was it like growing up in a town where there’s so much dedicated to one sport?

Pretty early in my childhood A League of Their Own came out, and it was filmed partially here. That was my entrance into baseball; I didn’t really get it until A League of Their Own, where there are these fierce women playing baseball. And the fact that it was filmed here made us all feel very famous. And so it was well-loved for that reason.

Aside from that, baseball was just sort of a nuisance. I grew up in a place that’s actually on the outskirts of Cooperstown and the outskirts of Oneonta. Oneonta is now building out its baseball infrastructure and even calling itself Cooperstown. Cooperstown Dream Park is actually in Oneonta. So baseball is spreading and it’s becoming a big part of why people are building houses here in order to Airbnb them in the summertime.

But when I was growing up, baseball season was tourist season. It just meant not a lot of parking in town. I worked at a bakery on main street in Cooperstown as a teenager and the summers were so intense with tourists. But another aspect of Cooperstown — in the summertime at least — is the Glimmerglass Festival, which brought a lot of queer people to town. I didn’t know this until I was a teenager and was starting to encounter those folks through working in the bakery. That was an interesting sort of parallel universe to the baseball tourism.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.