Nicolas Cage’s filmography contains multitudes. You could easily program film festivals with his forays into period dramas, action films or absurdist comedy. He’s done memorable work as a leading man and as a supporting player — and even now, decades after his career began, he retains the ability to surprise audiences.

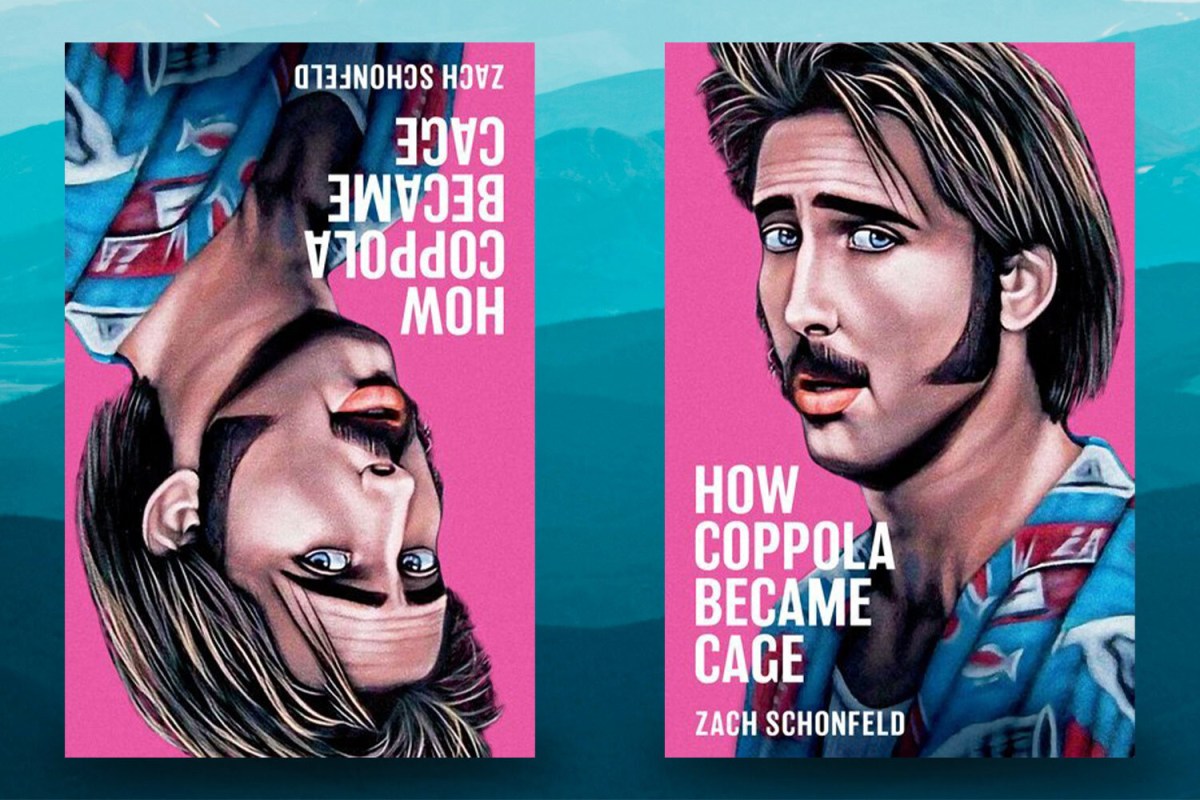

For his new book about Cage, journalist (and occasional InsideHook contributor) Zach Schonfeld went back to the beginning, exploring Cage’s career from his early days through his triumphant Oscar win for Leaving Las Vegas. The result, How Coppola Became Cage, is a deep dive into Cage’s history and the production of some of his less-heralded yet eminently worthwhile films. Readers will find it hard to finish Schonfeld’s book without wanting to track down Red Rock West — serendipitously reissued on Blu-ray this year.

InsideHook spoke with Schonfeld about this book’s origins in a feature he wrote about Vampire’s Kiss, Cage’s work with several of contemporary cinema’s best-loved auteurs and what might be next for the ever-shifting actor.

InsideHook: In How Coppola Became Cage, you wrote about how the book grew out of an article you’d written about Vampire’s Kiss. Was there a point in that initial article when you realized that it could become something more?

Zach Schonfeld: I encountered Vampire’s Kiss for the first time around the time that I interviewed Nicolas Cage for Newsweek in 2015. I was already a fan but I hadn’t seen everything that he had done, especially in his early years, and so while preparing for that interview and also after the interview I went down this Cage rabbit hole. I sought out a lot of Cage movies that I’d never seen before — some of the hidden gems of his filmography like Bringing Out the Dead, Birdy and The Weatherman.

I watched Vampire’s Kiss and that movie instantly became my favorite Cage performance. There’s just something so dark and disturbing and larger than life and expressionistic about his performance in that movie that really spoke to me. Around the same time I also read this book by Lindsay Gibb which I i quote and mention a few times in my own book: National Treasure: Nicolas Cage. It’s a pocket-sized book that gives an overview of Cage’s whole career and makes the case that Cage is a misunderstood genius whose brilliance has been repeatedly misconstrued. The book makes the case that Cage is an actor whose talents as an actor have never been properly appreciated by the ruling class of Hollywood.

Fast forward a few years. In 2019 I realized that the 30th anniversary of Vampire’s Kiss was coming up and I decided to do a feature where I would interview the producers, the director, the screenwriter and the cinematographer. I tracked down a lot of people involved with the making of the film and it became clear to me that everyone involved had a wild story about working with Nicolas Cage and how intensely committed he was to the performance — and the extreme and somewhat masochistic lengths that he went for the sake of it.

It became clear to me that everyone who worked with Cage — especially during the formative years of his career — has an interesting story to tell. There’s no one who worked with Nicolas Cage and said, “Oh yeah, he’s a normal guy, like I don’t remember much about him.” He made an impression on everyone who worked with him. That piece ran in The Ringer and it got a lot of attention. There’s a story of Cage swallowing a live cockroach because he thought that that’s what the movie demanded. There’s a story of Cage getting into a fight with the producers because he was insistent that they needed to use a real live bat for the scene when a bat swoops into his apartment.

During the course of recording that piece I interviewed one of the producers of Vampire’s Kiss, Barbara Zitwer. She was so heartbroken over the commercial failure of that film — she was a young film producer at the time — and when the film flopped she was so heartbroken that she left the industry and became a literary agent. She now runs her own literary agency — which is ironic because Vampire’s Kiss is a movie about a deranged literary agent.

She was one of my sources and after the piece came out she reached out to me and suggested that we meet for coffee. She encouraged me; basically, she said, “You could write a whole book about Nicolas Cage and I would be your agent.” That’s where that’s where the idea started. One of many book ideas that I’d toyed with in my brain was an oral history of Cage’s career in the 1980s, ending with the filming of Wild at Heart in 1989.

I never would have pursued this idea if not for Barbara offering to represent me and encouraging me to actually write a book proposal about Cage. I decided that I didn’t want to use the oral history format. I wanted it to be narrative nonfiction and I also ended up deciding during the process of writing this proposal that it didn’t really make sense to end the book with Wild at Heart. It made more sense to end the book with Leaving Las Vegas, the film that Cage won an Academy Award for in 1996. It just made sense that the story should end with Leaving Las Vegas — that was the culmination of everything that he was working towards for the first 15 years of his career.

There’s been a lot of Cage discourse lately. You brought up the book National Treasure and in your book, you cite Nathan Rabin’s Travolta/Cage Project. There’s also been Keith Phipps’s Age of Cage, which uses Cage’s career to look at the American film industry more broadly. It’s hard to think of too many other actors who could serve as the muse for such wildly disparate projects; what do you think it is about Cage that allows him to do this?

One thing about Cage is that he’s a cultural chameleon. He has given so many different types of performances in so many different types of movies. There are people who revere him as the romantic lead in Moonstruck, and then there are people who know him as an action hero, the guy who made $20 million a movie and was at the peak of his game during the late ’90s action movie boom. And there are people who love his weirder, more avant-garde performances in Vampire’s Kiss and Bad Lieutenant: Port of Call New Orleans. In recent years he’s also been kind of down on his luck, pumping out straight-to-VOD movies to pay off his IRS debts, and there are younger people who know him as a meme, from silly internet gifs, novelty merch and YouTube supercuts of him freaking out in many different movies.

As a journalist I’m very interested in origin stories. I’m always fascinated to know where a cultural icon came from and how they became who they are. Cage has a particularly juicy and intriguing origin story because he grew up in the shadow of a world-famous film director. He also had a very troubled childhood: his mom was mentally ill throughout much of his childhood and she was institutionalized for a large period of his childhood, which was the great trauma of his early life. His dad was an eccentric literary professor who by all accounts was a brilliant man but very emotionally distant and wasn’t a very supportive father.

I really wanted this book to be about the origin story of an American icon. I think my skill as a journalist is that I’m very good at tracking down sources — famous sources but also people who have not been interviewed on the record before. For this book I tracked down Cage’s high school friends. I talked to people who knew him when he was just starting out; I talked to the co-stars of a failed television pilot that Nicolas Cage and Crispin Glover made in 1981. I interviewed casting directors and cinematographers and dialect coaches — all kinds of people who have played a significant role in various movies that Cage has made but people whose names you wouldn’t recognize.

I knew that in order for this book to be worth anyone’s time and hard-earned cash, I needed to interview a lot of sources and unearth stories and anecdotes and insights into Cage that have not been published before.

Did your feelings on Cage shift at all over the course of researching and writing the book? Were there any conceptions of his work that you had that ended up being challenged or altered as you got deeper into it?

I think one thing that became clear to me through all the years of researching Cage is that he’s a true cinephile. You’ll read interviews with him where he will mention his love of German expressionist films from the 1920s, like Nosferatu, or he’ll mention his obsession with Fellini films from the ’60s. I can tell you it’s not an act; it’s not a put-on. He really is just an obsessive film nerd. He was raised that way by his father. When he was a kid and his friends from school were watching Disney movies, his father was showing him Fellini’s Juliet of the Spirits.

He was raised with this deep obsession and curiosity about film, and something that became clear to me is that a lot of the movies that he’s done where you might think that he’s just going off the rails and going rogue and acting like a wacko, he’s riffing on something he’s seen in a classic film. To give a prominent example, in Vampire’s Kiss, he does these distorted and heightened facial expressions. There’s a scene where he’s walking through the nightclub with his shoulders really stiff. He’s paying tribute to Max Schreck from the 1922 film Nosferatu which was a huge influence on his performance inVampire’s Kiss and one of Cage’s favorite movies.

When you read interviews with him, you’ll realize that he’s imitating his heroes. He’s very much like a young film nerd at heart, just trying to pay tribute to his famous actors and the people who he grew up watching.

Towards the end of your book, you mention the almost preternatural affinity Cage had for the author of the original novel Leaving Las Vegas, John O’Brien. It was uncanny to read about that.

It’s an eerie story because John O’Brien died by suicide right after he sold the film rights to Leaving Las Vegas. Cage felt as though John O’Brien’s spirit hung over the film. John O’Brien’s family was very, very moved when they watched Cage portraying a character who was clearly a semi-autobiographical portrait of the author John O’Brien.

Cage decided that his character should drive a black BMW in the film, and that was the same car that John O’Brien drove. When Cage won the Oscar and the Golden Globe, in both acceptance speeches, he said something like, “I want to thank the late John O’Brien, whose spirit moved me so much.”

One of the fascinating things about your book was learning about projects Cage was almost in, or other actors who almost played some of his most famous roles. It’s hard to imagine Kevin Costner as H. I. McDunnough in Raising Arizona. Was there anything that you discovered in terms of films that might have been or roles that might have been that you hadn’t known going in?

I love learning about those alternate realities, like Cage almost starring in Dumb and Dumber. It’s hard for me to imagine him doing such a crass comedic role. When you really think about those stories of how someone almost starred in this movie instead of Nicolas Cage, it makes you realize how much the success of a movie hinges on decisions that almost didn’t happen.

Norman Jewison, the director of Moonstruck, and Cher had to fight for Cage. Cher was Cage’s champion; she really believed that Cage was the man for the job, and the studio was not comfortable with Cage because he wasn’t exactly leading man material at that time. Something that I found fascinating was that Peter Gallagher was the other contender to play Ronny. Cher basically threatened to back out of the film if Cage wasn’t her co-star. I don’t know if Moonstruck would have worked with Peter Gallagher. I cannot really imagine that working as well because Cage brings this torment and sexual bravado, but also this tormented anger and energy to that movie — which, in my opinion, is a big part of what makes the movie great.

When it comes to Cage, the big alternate history is that he was supposed to star as Superman in Tim Burton’s Superman movie in the late ’90s. Cage has revered Superman since he was a small child, and Cage has always been drawn to troubled, haunted superhero-type characters. So we were robbed of something. I don’t know if it would have been great but at the very least it would have been interesting to see Cage play Superman in a Tim Burton movie with a huge budget.

This New Book Revisits Francis Ford Coppola’s Complex Artistic Vision

Sam Wasson on writing “The Path to Paradise: A Francis Ford Coppola Story”Relatively early on in your book, you brought up the fact that Cage hasn’t worked with many directors multiple times, unlike many of his peers. Do you think that’s something temperamental, or is it more of a case of Cage wanting to work with as many directors as he can?

I’ve wondered the same thing, why Cage hasn’t found a director that he can just work with over and over the way Leonardo DiCaprio is always working with Martin Scorsese. Early in his career, he had that relationship with his uncle. He was in three Francis Ford Coppola movies in a relatively short span, and then my understanding is that Cage’s performance in Peggy Sue Got Married was so wacky that Coppola was pretty frustrated with him and and ended up never working with him again. To the point that Cage was actually quite offended that Coppola didn’t give him a role in The Godfather Part III.

I don’t know why Cage has never worked with the same director more than three times. When I interviewed David Lynch for the book — which was an unexpected honor — I asked him about that. Lynch loved working with Cage; he was effusive about how much he loved Cage and how those two really hit it off, they really had some kind of some kind of mystical connection. And yet Lynch never worked with Cage in a feature film capacity ever again. He did do a short film with Cage and Laura Dern that was kind of like an extension of Wild at Heart.

David Lynch said it wasn’t right for some reason and it never happened, but it could happen tomorrow, you never know. He said, “I think he’s one of the all-time greats.” I think maybe part of it is that not that long after Wild at Heart, Cage became one of the highest-paid actors in Hollywood after The Rock and Con Air. By that point David Lynch couldn’t afford him anymore. He was no longer doing low-budget films; he was outside of David Lynch’s pay range and John Dahl’s budget range — the guy who made Red Rock West.

But then in the mid-2000s, Cage went back to doing some lower-budget projects like The Weatherman and Bad Lieutenant and Joe. So I don’t know why he hasn’t had that kind of long-running relationship with a director. I would love for him to work with Werner Herzog again or work with his uncle Francis Ford Coppola — why isn’t he in Megalopolis?

That’s surprising to me, too, especially since Coppola’s recent projects have had a more surreal style that you’d think Cage’s approach would be a perfect fit for. It’s also interesting that the lead of Megalopolis is Adam Driver, who’s an actor who has more than a little in common with Cage in terms of what he brings to a role.

They both give off the sense of like just pouring everything they have into every role they play. I was thinking about how Adam Driver is now working with Francis Ford Coppola, Cage’s old collaborator — and it just occurred to me that fairly early in his career, Cage worked with Francis Ford Coppola, the Coen Brothers, Martin Scorsese and Ridley Scott. And now, Adam Driver has worked with all of those directors.

I think there’s something interesting about how both Cage and Adam Driver have been in demand among the great auteur filmmakers of our time but you still have people who don’t take them fully seriously. People dismissed Cage early in his career because he was a Coppola and because he was so wacky that a lot of people didn’t take his talent seriously. And I think people also don’t fully take Adam Driver seriously because to much of the population, he’s still that fuckboy from Girls. I think there is a parallel between Cage and Adam Driver, but I don’t think Driver is quite as eccentric as Cage.

One other director who Cage has never — to my knowledge — worked with that I think could be very interesting is Noah Baumbach. They’re both children of hyper-literary fathers who they seem to have very fraught relationships with. I feel like that could make for something truly fascinating or it could make for an absolute disaster.

Cage has recently been in this career renaissance, and he apparently paid off all of his IRS debt a few years ago so he can now afford to be more selective about which film projects he takes on. In interviews lately, Cage has been saying that he’s going to be much more selective now. I think that’s his way of sending out a signal to people like Noah Baumbach or Paul Thomas Anderson that if they want to work with him, they’d better hurry up. He’s not going to say yes to everything anymore and he might not be making movies forever.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.