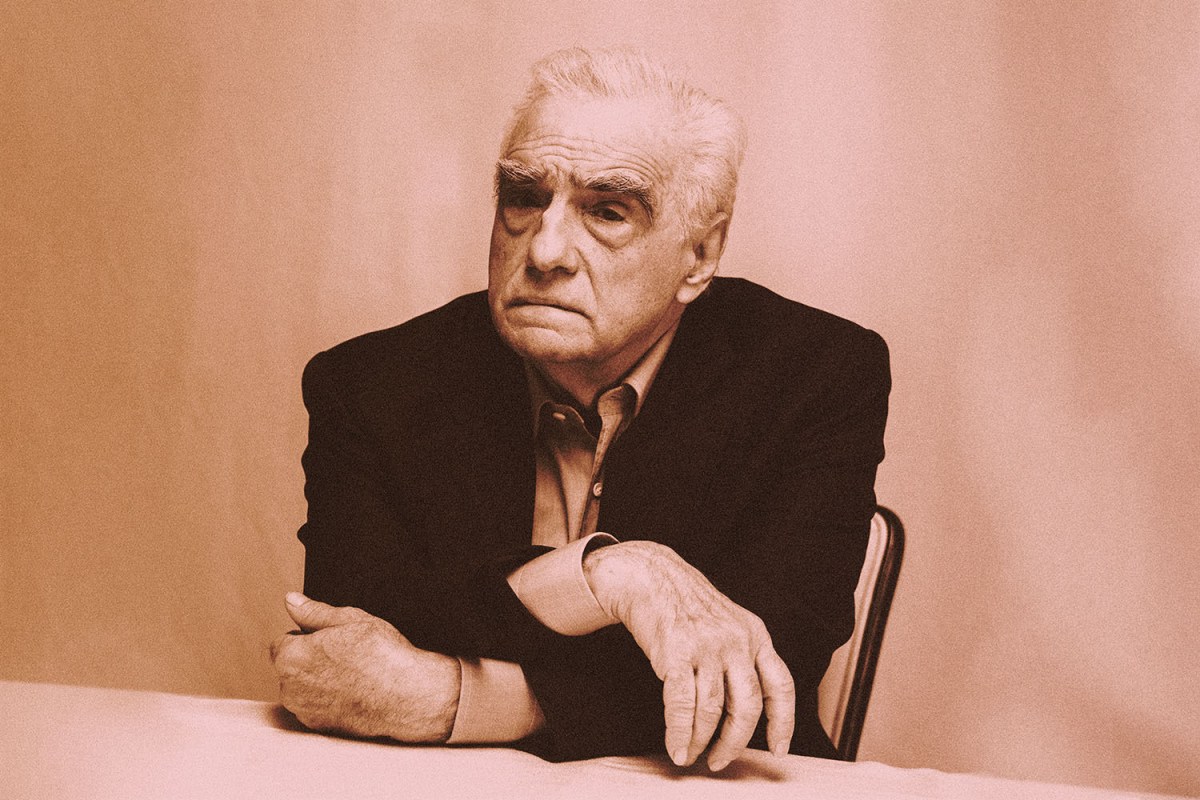

Martin Scorsese, the 78-year-old American filmmaker and film preservation advocate, has an article in the March issue of Harper’s about Federico Fellini. Fellini, he writes, “was the cinema’s virtuoso,” in whose films sound and image “play off and enhance one another in such a way that the entire cinematic experience moves like music, or like a great unfurling scroll.”

But that’s not why you’re reading this, is it?

Scorsese can get lots of people Very Mad Online by making simple factual statements about what the corporate consolidation of the American film industry is doing to American art and culture. He did it in 2019, when he wrote in the New York Times that risk-averse “modern film franchises [are] market-researched, audience-tested, vetted, modified, revetted and remodified until they’re ready for consumption,” a pattern that squashes individual artistic expression while crowding out other options in the theatrical marketplace. Presumably at least some of the people who were angry at Scorsese for comparing Marvel movies to “theme parks” then are the same people who will soon eagerly pony up to visit the Marvel Studios Theme Park Universe.

In his Harper’s article, he makes a parallel point about streaming. (It’s worth reiterating that, in this era of unparalleled corporate mergers, Scorsese is vilifying the same people when he talks about superhero movies and when he talks about streaming. Marvel and Disney+ are under the same corporate umbrella; the DC universe and HBOMax are both subsidiaries of AT&T; and streaming services born out of the tech world, rather than from mergers between telecoms and legacy studios, have their own off-brand franchises.) This time around, Scorsese’s argument is that through streaming platforms, “the art of cinema is being systematically devalued, sidelined, demeaned, and reduced to its lowest common denominator, ‘content.’”

Here’s the crux of the thing:

[T]he people who took over media companies [mostly] knew nothing about the history of the art form, or even cared enough to think that they should. “Content” became a business term for all moving images: a David Lean movie, a cat video, a Super Bowl commercial, a superhero sequel, a series episode. It was linked, of course, not to the theatrical experience but to home viewing, on the streaming platforms that have come to overtake the moviegoing experience, just as Amazon overtook physical stores. On the one hand, this has been good for filmmakers, myself included. On the other hand, it has created a situation in which everything is presented to the viewer on a level playing field, which sounds democratic but isn’t. If further viewing is “suggested” by algorithms based on what you’ve already seen, and the suggestions are based only on subject matter or genre, then what does that do to the art of cinema?

Look, I haven’t checked Twitter, I assume that some piggies are once again angry at Scorsese for seeming to turn up his nose at the smell of their slop, but I’m struggling here to say something more than “He’s right and he should say it.” Because he is right: When “everything from Sunrise to La Strada to 2001 is now pretty much wrung dry and ready for the ‘Art Film’ swim lane on a streaming platform,” that makes it harder for the next Fellini, or the next Scorsese, to unfurl their scrolls across the hearts and minds of an audience hungry to be changed. And he should say it: It doesn’t have to be this way. Developing a sense of discernment about art, discovering distinctions and navigating affinities, rather than letting it all blend together in a soylent-y mush, is one way a person teaches herself to be curious about the world.

“Curating,” like the work of the distributors and exhibitors who showed Fellini films in the Village, “isn’t undemocratic or ‘elitist,’” Scorsese writes: “It’s an act of generosity—you’re sharing what you love and what has inspired you.” This, indeed, is how work carves out a lasting space in our social consciousness. When enough people share in their love of a piece of art, that art becomes part of a community. There’s no inherent power imbalance at play in the exchange of enthusiasm or insight from one person to another. And if there is, take it up with studio head, streaming platform developer, newspaper owner and future President-for-Life of Mars Jeff Bezos.

To Scorsese, who has lived with movies ever since he was an asthmatic boy with an active imagination, who stayed inside watching films instead of playing sports, film is a living art. Scorsese is not afraid of a modern world that has passed him by; to the contrary, he remains a filmmaker thrillingly attuned to the vital currents in American culture, from our Icarus-like grandiosity (The Wolf of Wall Street) to our nostalgia, conspiratorial mindset and stunted masculinity (The Irishman). The Harper’s essay begins like a screenplay, with a flashback: “CAMERA IN NONSTOP MOTION is on the shoulder of a young man” walking through Greenwich Village in New York, drinking in the theater marquees advertising films by Bergman and Truffaut. It’s touching and sad to see Scorsese, once that ardent, agitated young man, treat Fellini in this essay as both the quintessential cinematic artist, and as a figure from history — and to reckon, implicitly, with his own impending consignment to the same antiquities wing.

I guess to some, Scorsese’s complaints about the death of cinema, about algorithms superseding the mystical powers of human connection, might just sound like an out-of-touch fogey. Why, you used to hear similar crankiness about what the tech industry would do to commerce through Amazon (which has destroyed the livelihoods of countless local small business owners); what it would to socialization through Facebook (the world’s largest distributor of child abuse images, and the proximate cause of a genocide in Myanmar); what it would do to the media through Twitter (a shitswamp, just an absolutely terrible place). The promise of the tech industry — of automation, artificial intelligence, machine learning — was that it would take over our labor. In fact it’s taken over our leisure. Amazon warehouse workers piss into bottles because the bathroom is too far away to get to on their breaks, but at least they don’t have to think too hard about what to watch on TV when they go home.

Scorsese winds his essay up towards a rallying cry: Great films are “among the greatest treasures of our culture, and they must be treated accordingly.” How? How do we keep all art from being blended into the same soylent-y mush? I don’t know, and neither does he. In 2019, Scorsese wrote that he’s “certainly not implying that movies should be a subsidized art form.” He seems, like a good liberal, to place his hopes on benevolent intentions and virtuous incentives in the marketplace of ideas. We’ll see how that goes. In the meantime, Martin Scorsese has earned the right to shoo these kids off his lawn. They’re trampling the flowers.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.