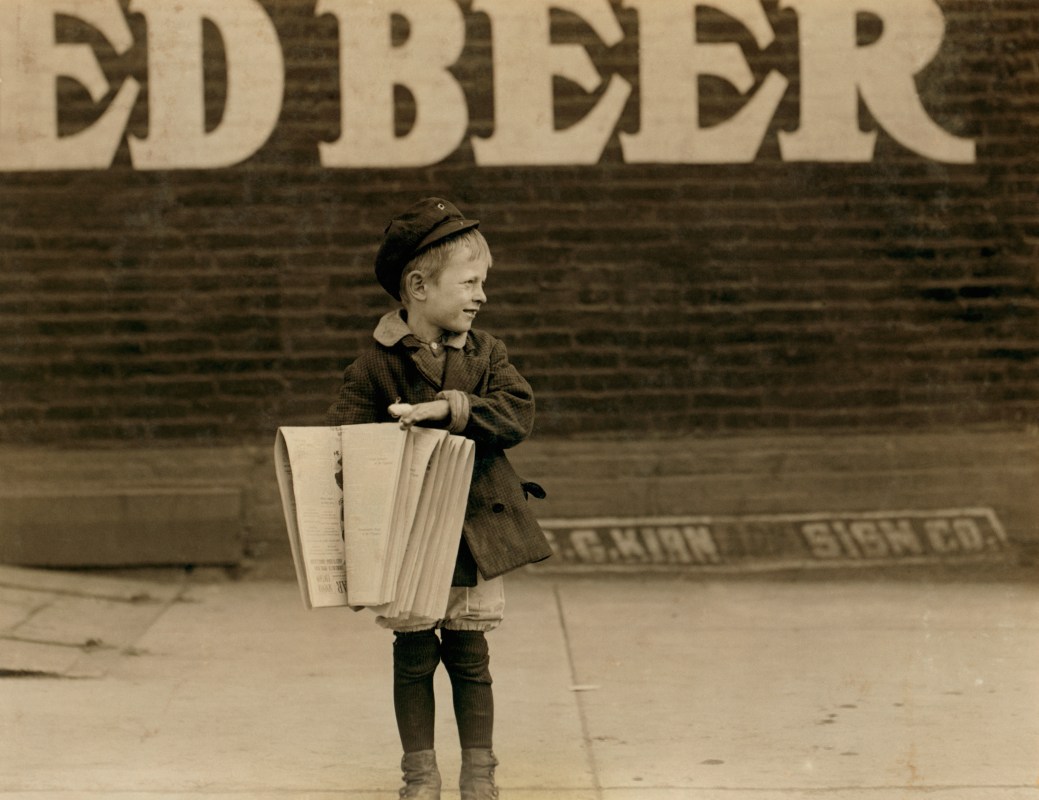

Over the weekend, a senior research associate and instructor at the University of Calgary named Paul Fairie posted a Twitter thread titled “A Brief History of Kids Are Too Soft.” It’s an absolute doozie. Fairie, who regularly tweets out “curiosities” he’s found by combing through records of old newspapers online, discovered a fascinating trend: embittered writers have been lambasting younger generations for over a century.

They’ve specifically made use of the phrase “too soft,” which many might assume is a modern invention. Type “today’s kids too soft” into a search engine, and you’ll be greeted with an angry array of op-eds, Reddit monologues and YouTube videos, each packed with theories on why exactly the youngest among us are poised to doom us all. You know the highlights: screen time, participation trophies, shifting gender norms, lack of service in the military, more years spent living in their parents’ homes. Surely all these lazy, incompetent, entitled, triggered, Uber Eats-ing trustafarians aren’t equipped to handle the rigors of the world, or attack the future with the grit that this country requires, right?

If you feel that way, congratulations, you’re doing your part to continue a historic tradition. The first mention of “too soft” that Fairie found was in 1921; the writer complained that “the youngsters of 1921 are setting too fast a pace.” They declared: “There are too many high powered cars parked around the high schools. The kids have it ‘too soft’ for their own good.” They then went on to offer a sparkling solution: more spanking. “If those Kansas City mothers will just come to an agreement to see to it that their boys and girls are soundly spanked until they are made to like it, they will have little further cause for worry.”

Spanked until they are made to like it. Indeed. The “boys and girls” this writer is referring to were likely born between the years 1905 and 1908. They grew up through World War I, the 1918 influenza pandemic and Roaring Twenties, and would come of age during the Great Depression and serve as older G.I.s in World War II. In other words, they were Tom Brokaw’s “Greatest Generation.” Unfortunately, we’ll never know what they might have actually been able to contribute to the United States of America had they only been spanked a bit more.

A year after that line was written, a clipping in an Ohio newspaper, the Evening Independent, reported on the awards being handed out at a high school basketball tournament. The correspondent wrote, “Members of the victorious outfits will be given individual trophies. A participation trophy also will be given to each athlete playing in the series.”

Kids being blamed for the downfall of society, kids being blamed for trophies they didn’t ask for…none of this is new. Fairie’s “too soft” thread is a walking tour through the decades: here kids are dancing too much in juke joints, here they aren’t climbing trees anymore, here they’re obsessed with Nintendo and skateboards. The overriding thesis of these columnists, teachers and parents can be summarized by a quote from one mother in a 1961 article: “We have done our children irreparable wrong. From before conception we planned only how to make life easy for them. Now as they approach adulthood we are still cushioning them from reality. I hesitate to think what will happen when they run up against a real problem and we are not there to pay the expenses and sooth their injured egos.”

Does this mother actually “hesitate to think,” though? Or is she, like countless others, somewhat excited to share these thoughts, and, perhaps, even hoping to be proven right?

In truth, the trickiness of intergenerational relationships transcends geopolitical headlines or the newfangled technology of a given era. Aging folks thinking very little of young bucks is a constant; it speaks to the pain of accepting that life on the planet is short, and eventually it will be someone else’s turn. Usually, that someone else wears different clothing, uses unfamiliar slang, has opinions that you don’t agree with, and can expertly navigate all the new toys you never had the energy or time to master.

In some ways, this turnover must feel like an alien invasion. But it’s just a changing of the guard. Younger generations aren’t taking the world over, they’re inheriting it. It’s a very human trait to fear, as this transition nears, that one’s name and legacy will be forgotten. But that insecurity shouldn’t come at the expense of treating newer, younger names with dignity, patience and respect. (Which might teach them, in turn, to return that treatment in kind.) If you want to be remembered, wouldn’t you rather have future older generations recall all the kindness, grace and wisdom you imparted? ‘Tis better to be a steward than a spanker.

This is so much easier said than done. As Vox wrote back in 2019, the same Gen Z kids incanting “OK, boomer” will likely one day complain about the narcissism, sloth and incompetency of whatever generation comes of age in the 2050s. It’s possible that the seductive tendency to minimize the efforts and traumas of the subsequent generation arrives because the previous one had trouble acknowledging your efforts and traumas. Consider today’s youngest. What Millennials and Gen Z have weathered over the last 20 years is alarming: terrorist attacks, school shootings, extreme natural disasters, social media-related suicides, a once-in-a-century pandemic, meteoric college costs, rent increases, wage stagnation…the list goes on. Should there even be a list, though? Should any generation have to verbalize its struggles in order to prove its worth?

Breaking this cycle will be extremely difficult. Older generations may have only been tossing around “too soft” for a century or so, but the practice of dismissing children goes back thousands of years. As the Greek philosopher Socrates (supposedly) once said: “The children now love luxury; they have bad manners, contempt for authority; they show disrespect for elders and love chatter in place of exercise. Children are now tyrants, not the servants of their households. They no longer rise when elders enter the room. They contradict their parents, chatter before company, gobble up dainties at the table, cross their legs, and tyrannize their teachers.”

Horrible. The nerve of those ancient rabblerousers! How did society ever survive?

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.