For decades, the slogan “Extinct is Forever” has concisely made the case for environmentalism and conservation. Hearing stories about the last days of now-departed species like the dodo and passenger pigeon is unnerving stuff, raising questions of what it would have been like to see the last example of an animal die off, never to be seen again. For the musically inclined, there’s also a fantastic Mountain Goats song on the same topic that finds John Darnielle singing from the point of view of several now-extinct creatures.

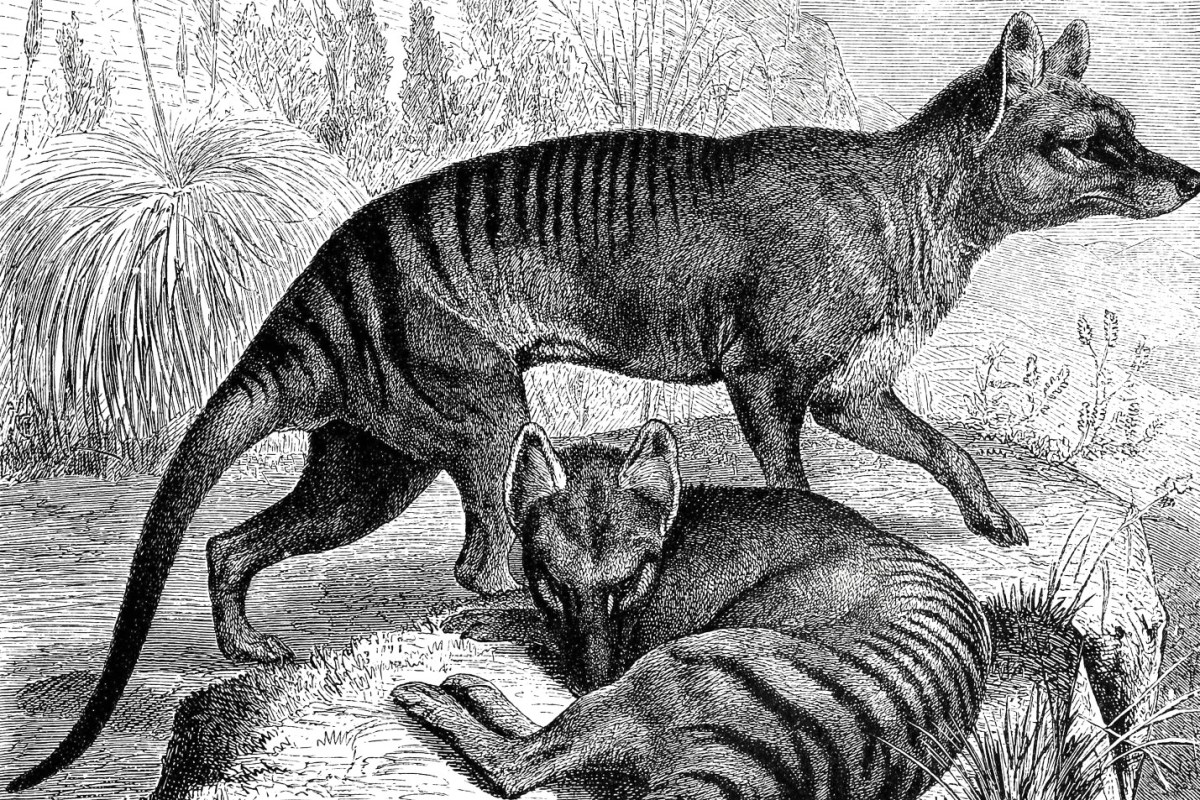

One of those animals is the Tasmanian tiger, or thylacine, which has been extinct since 1936, when the last example of the species died in captivity. Except maybe this predatory marsupial hasn’t been quite as extinct as scientists believed. That’s the biggest takeaway from a new article in Live Science by Sascha Pare. Some scientists, it turns out, believe that the Tasmanian tiger survived into the late 20th century, and didn’t become extinct until the 1980s or 1990s. And there are even some who believe that small populations of thylacines might still be alive in remote corners of Australia.

Giant Cane Toad Discovered, Euthanized in Australia

It may be the largest ever recordedThe scientists contemplating the thylacine’s extinction, or lack thereof, revisited archives of potential sightings from the early 20th century on. They paid especially close attention to “confirmed kills and captures, in combination with sightings by past thylacine hunters and trappers, wildlife professionals and experienced bushmen” in reaching their conclusions.

The paper summarizing their conclusions, “Resolving when (and where) the Thylacine went extinct,” was recently published in the journal Science of the Total Environment. But as Live Science’s reporting points out, not all scientists are convinced by the argument. That said, it’s also possible that an ongoing scientific endeavor might bring the Tasmanian tiger back from extinction, further complicating this discussion. Extinct is forever — except in the rare occasions when it’s not, apparently.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.