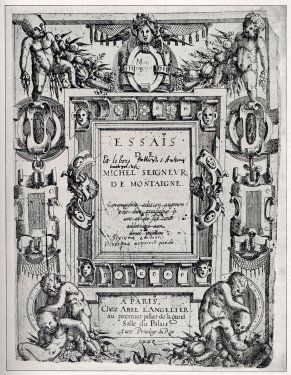

In 1580, in Bordeaux, Michel de Montaigne published a book unique in both its title and its content. The book is supposed to have been written “in good faith,” almost by itself, without a clear distinction between “the matter” it contains and the life of his creator; it is “a book consubstantial with its author.”

In this uncommon portraiture, Montaigne set himself no limits and embarked on judging almost everything that came to his attention. He accumulated essays on various topics, from thumbs to cannibals. A literary genre was born.

Creator of the essay, Montaigne served as a bridge between what we call the Early Modern and Modernity. This is how Montaigne is usually presented. However, in my political biography of Montaigne, I discover a man always aware of the political dimension of his work. It is too often ignored that Montaigne served as a parlement member, a mayor of Bordeaux, a negotiator between the king of France and the protestants, a special envoy to foreign courts, a diplomat and a political activist during the wars of religion.

Without denying the aesthetic and stylistic value of the Essays, I approached Montaigne’s work by the functions it had at various points in his life. Written over a period of 20 years, the Essays were published four times during Montaigne’s lifetime. Each edition differs from the preceding one not only in its content and form, but also in the political project that accompanies it.

I analyzed the successive transformations of a text that refers to conceptions, distinct and sometimes contradictory, of political commitment and public service. The literary and philosophical constitution of the Essays was greatly influenced by Montaigne’s concern to realize his political ambitions and aspirations. I tried to demystify the conventional image of the essayist isolated in his tower, far from the agitations of his time, playing with his cat and inquiring into the human condition. Even when he retired from society, the author of the Essays aspired to rejoin it and resume his political service.

Approaching the Essays on the basis of Montaigne’s social and political motivations gives a new and often unexpected dimension to the text. I wanted to offer a new light on the process of the mutation of the publishing project of the Essays over time. It is in the relationship between public life and private life—which was already complex between 1570 and 1580, and became paradoxical after 1588—that we can find the keys to interpret a text that had distinct political objectives for Montaigne at different moments in his life.

The purpose of my book is precisely to relate the two inseparable aspects of Montaigne’s life that are constituted by literature and political action. The essayist made several attempts at politics before his book transformed him into a literary monument. His successive failures in politics nonetheless allowed him to find the right tone for a new literary and philosophical genre that he built on the ruins of his career in public service.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.