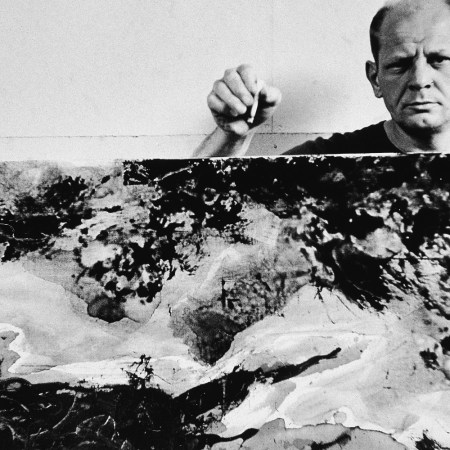

“Hot damn” reads a plastic container of neon yellow paint that’s shouting at me from a table in Erik Parker’s studio. The artist — whose work is currently in the collections of the Museum of Modern Art, Whitney Museum of American Art, Brooklyn Museum and many others — opened his Brooklyn studio to guests in time for the Frieze Art Fair in May, in partnership with Blundstone (he loves to wear the shoes before and after surfing). Parker and his team mix 95% of his colors, many of which he names himself; hence the “Hot Damn” dashed onto the container, accompanied by the likes of “Soaked” (dark, greyish purple), “King Tubby” (fluorescent red), “Fallin” (bright orange) and “Bumpin,” (light pink). There’s no rhyme or reason to the names, he says. It’s whatever jumps out at him first.

It’s a fitting sentiment as one looks at his work, too: this collection of neons and bold graphics on enormous canvases burst into shape following Parker’s whims, flirting with nostalgia. There are hints of Parker’s childhood — the posters he’d see in the bedrooms of friends’ older brothers, as one canvas is inspired by Welcome Back, Kotter, another by the band KISS. On two other canvases, cut into pyramids, small cutouts sourced from vintage High Times, Ebony and Playboy magazines become a scroll of imagery to latch onto, not unlike the way one might scroll on a phone. He wants to grab everyone as a viewer, he says, to feel like they have some sense of ownership to each canvas. It’s a more graphic approach to his earlier work, which featured extended cultural maps written in his own hand. Indeed, there’s one 2000 work in his studio that he bought back from a previous owner, “art power (cultural shout-outs),” which reads not unlike a teenager’s notebook or a 1980s/1990s hardcore show flier, beloved musicians and artists and writers scrawled onto its canvas in cloud-like formation.

It hearkens back to some of Parker’s earliest influences, many of which stemmed from the 1980s DIY punk scenes, including the work of legendary artist Raymond Pettibon, who designed early posters for Black Flag. Parker also cites MAD magazine as an influence, as well as the Chicago Imagists, Peter Saul and G&S skate stickers with designs by Neil Blender (Parker skated vert back in 1980s Texas), among many others. The underground, he says, is part of his lexicon as an artist. These were not always inspirations he saw highlighted in the art world when he moved to New York in 1996. However, Parker does remember finding inspiration in like-minded artists like John Currin and Elizabeth Peyton showing at Gavin Brown’s enterprise, a cool downtown art gallery with an adjacent bar called Passerby where everyone hung out. It served in part as his introduction to the scene.

His relationship to underground subcultures both artistic and not “was a way to jump on something that wasn’t being examined in the proper art world at the time,” he says. “You go into these galleries, they can be intimidating.” He remembers the ‘90s art world being more closed off ideologically, not as open to artwork that stemmed from more experimental or underground inspirations or points of view. “I think that the kind of gates are open a little bit more for more different kinds of things, and ways of looking and thinking about things,” he says. “Definitely our world in the ‘90s was more kind of uptight.”

Celebrity Photographer Greg Williams Takes Us Behind the Lens of 10 Photos

Wading into the ocean with Kate Winslet, wandering around Wes Anderson’s set with Bill Murray and other stories from his new bookTimes have changed, and some of what used to be underground isn’t so underground anymore; not only that, it’s also been embraced by the art world and even some of pop culture’s brightest stars. Parker recalls Travis Scott stopping by the studio. “That was weird. When I opened the door, his bodyguard just like pushed me out, and I was like, ‘yo, it’s my spot!’” he laughs. But Parker also counts among his fans the likes of Swizz Beatz, soccer player Sergio Ramos of Paris Saint-Germain F.C. and the Miami Heat’s Jimmy Butler. It doesn’t hurt, either, that he entered the Hypebeast-sphere a while ago, which he estimates is because of his friendship with Kaws, artist Brian Donnelly. “I like that whole vibe,” he says. “It turned into sneakerheads starting to collect art.” He estimates many got involved in art through sneakers, through Kaws’s work.

Parker feels positively about the way this cultural shift has affected the art world, especially as it relates to social media. “I think because the wall was put down with Instagram,” he says. “I know cats that never went to an art history class and know everything about the art world. People are excited about looking at art. Like, MoMA’s packed. Twenty-five years ago [there] was not a line around the block. People are into art more.” Parker’s work, with its eye catching-vibrance, has become a hot commodity as well: indeed, with gates lowered, there became more space for work influenced by underground comics, graffiti and DIY punk scenes.

The audience remains significant for Parker. He makes his work to be collected, to be seen, and isn’t shy about saying so. Should anyone be? “I would say that people just don’t come out and say it,” he says. “Why are you going to make things in a room and then have them hung in a space, open to the public, and not want people to want to see that?” He remembers having a daughter young, being broke and needing to make money, wondering how to create a career as an artist. You had to get seen. You had to create an audience. So he did.

With all of its neon flourishes and craftily warped sensibilities, his work is visible not just in physicality but in philosophy. It has a space in the art world that may have been harder to take up 30 years ago. “I don’t really care about being the smartest guy in the room, but I want to be an artist’s artist, or like, just appreciated,” he says. “So I think that’s why I do it. You could literally cut that whole thing short [and just say] I want to be loved. Just tell me you like it.”

This article was featured in the InsideHook NY newsletter. Sign up now for more from all five boroughs.