There was still plenty of movement before the rise of agricultural human societies. Empires rose: some flourished, some perished and some just persisted. But in the 16th century, everything began to change, and quickly. Agricultural development was slowly replaced with a new mode of living. There were revolutions in what people ate, how they communicated, what they thought, and the relationship they had with the land. Then, Europeans arrived on what they named America. The people on the Americas had been isolated from those of Asia and Europe for about 12,000 years.

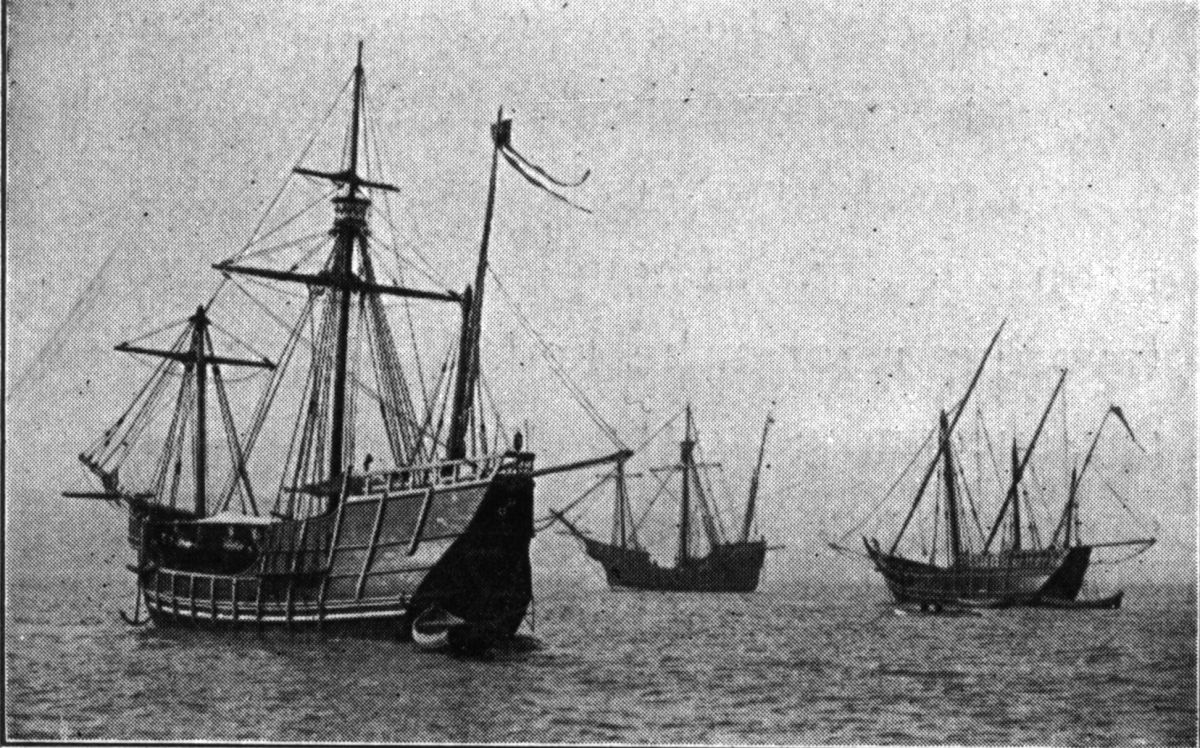

Did the re-joining of two branches of humanity after so long change Earth’s history as well as human history? When Native Americans met Europeans, everyone began to fall ill and die. Native Americans had no prior exposure to swine flu, which the Europeans brought over. Better ships were built, ones that cut the time it took to sail across the ocean, which allowed diseases to hitch a ride.

A new book by Simon L. Lewis and Mark A. Maslin, The Human Planet: How We Created the Anthropocene, looks at how biodiversity around the world were impacted by disease, conquest and a global shipping network.

Thanks for reading InsideHook. Sign up for our daily newsletter and be in the know.