It’s often said that good writing, like good art in general, isn’t motivated by money. Aspiring writers are fed this advice more often than not, and to some extent, it’s true: the arts are not a stable marketplace, so pursuing them should be done out of love for creating, and not as a quick cash grab.

However, as the New Republic points out, the relationship between writing and money has always been complicated. The patronage system, in which “poets would provide wealthy benefactors with writing that extolled their virtues, as well as act as … creative writing coaches for the patron’s own work,” was purposefully ambiguous, but can be boiled down to rich people directly supporting writers they liked.

The Greek poet Simonides upended this system by essentially freelancing instead of aligning with a patron, and was shamed for generations afterward as the personification of greed. But his tactic of writing directly for money and keeping records of what he was owed is pretty normal by modern standards, and begs the question of how other famous writers actually got paid. Or didn’t, in some cases.

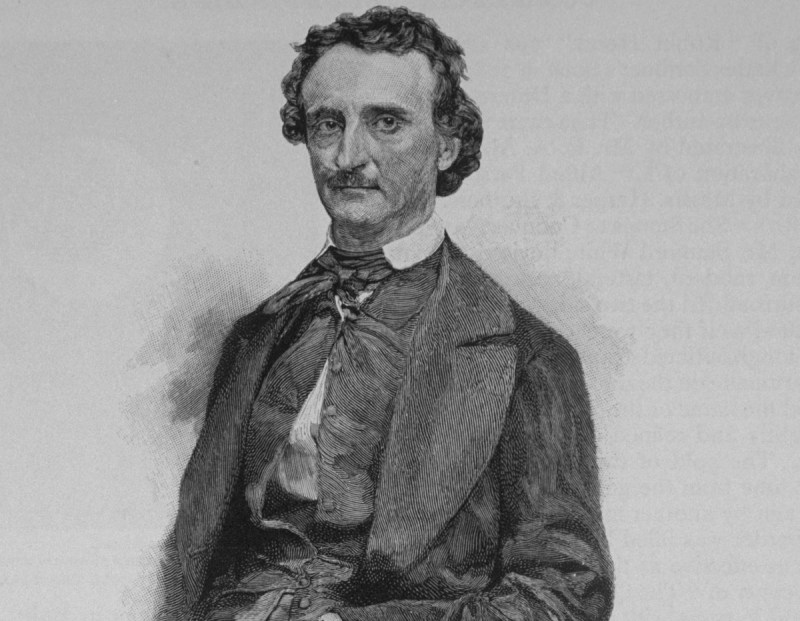

The first well-known American writer to try and make a living just by writing was Edgar Allan Poe, who picked maybe the worst time in the history of American publishing to set out on his own. The lack of international copyright laws meant that publishers could reprint work from, say, Charles Dickens for free, rather than pay an American writer. Plus, even when they did publish Poe’s work, they often refused to pay him, or underpaid him (he only got $9 for “The Raven,” for example). Poe did manage to make money through a touring show where he read his own work before a live audience, and through his own publishing efforts, but his career was plagued by financial issues until his death.

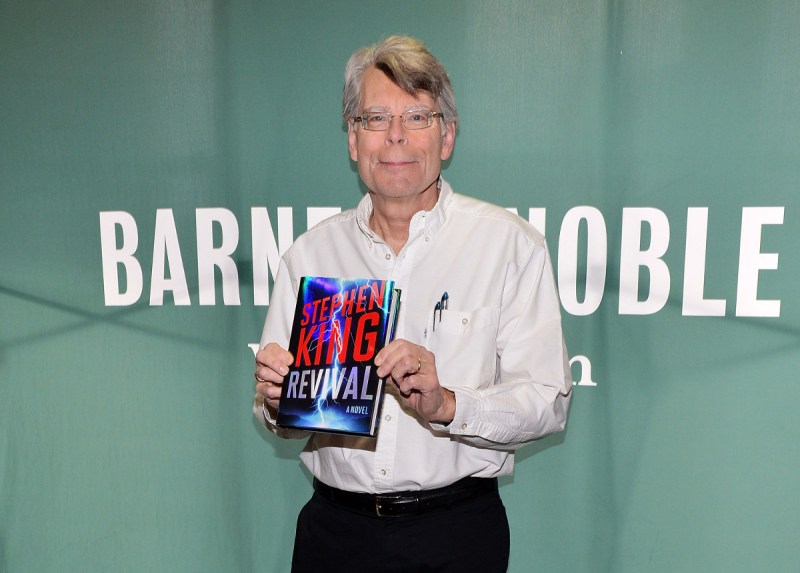

Stephen King toiled in the weeds as a writer for years, sending short stories to literary magazines (and gentleman’s magazines like Cavalier) for years, supplementing that income by working in mills and laundry facilities, and eventually teaching English. When he finally struck it big with Carrie, he received a $2500 advance from Doubleday for the hardback. New American Library would later buy the paperback rights for $400,000.

James Patterson, currently one of the most successful writers in the game, was an advertising executive and only took up writing full-time in the 1990s (his first novel was published in 1976). The success of his thrillers, and the pace at which he and his co-authors crank them out, led Forbes to estimate that a 2011 book deal landed him $150 million, a figure Patterson disputed. Patterson currently operates as a brand more than a traditional author, generating ideas for co-authors and making serious bank from book sales, movie tie-ins, and other revenue generated by his books.

And finally, legendary gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson made a lot of noise about his life as a freelance writer; a volume of his personal correspondence is full of letters to publishers, colleagues, and friends that, with no detail spared, catalog the many frustrations of writing for a living. Thompson kept detailed invoices of his expenses and accounts, and wasn’t shy about disputing royalty payouts or dishing about publications that, in his eyes, had burned him or wasted his time. He was often peeved about what he earned from his Hell’s Angels book, and held his literary agents and Random House responsible for his low earnings from the book.

—RealClearLife Staff

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.