When it comes to menswear, pockets are ubiquitous. That’s largely a good thing, as it can make activities from the quotidian to the formal that much easier to accomplish when you have necessary objects on hand. Though there can be downsides to this: at a wedding last month, I found pages of notes I’d jotted down years before, the last time I was wearing the jacket I donned for the celebration.

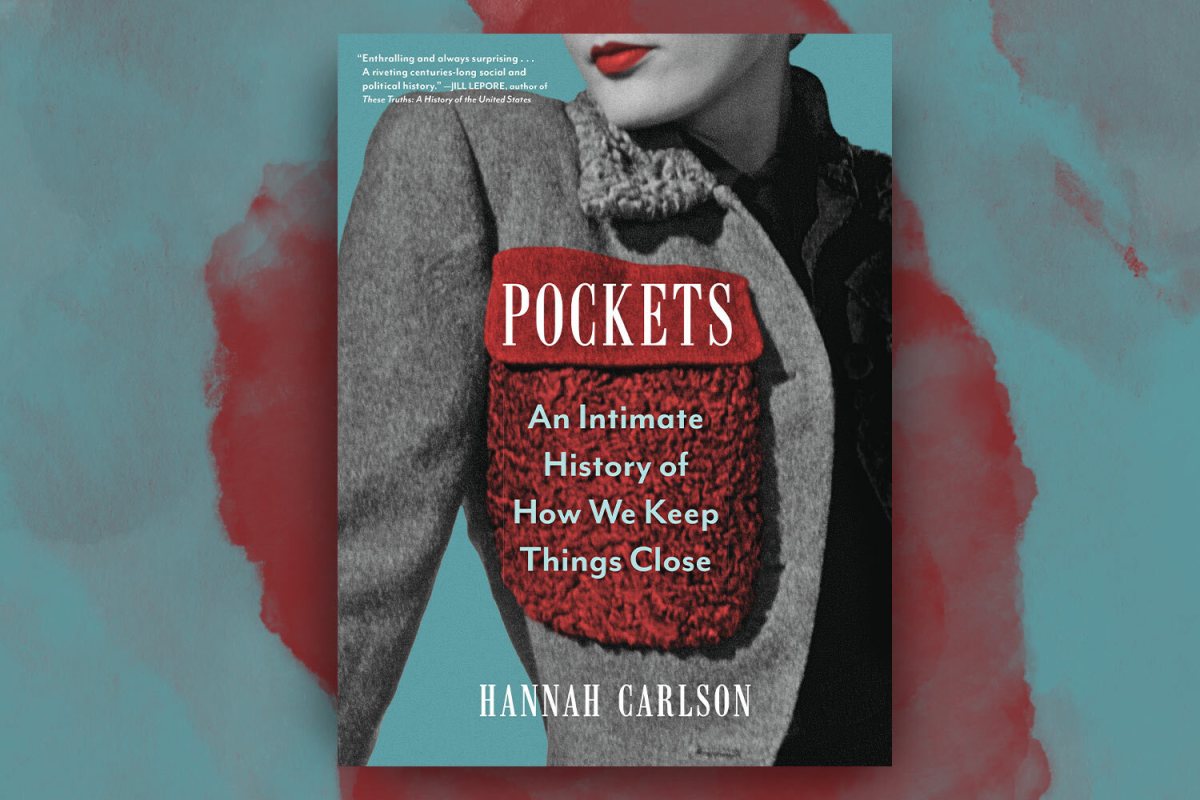

There’s a lot that we might take for granted about pockets, and that’s one of many reasons why Hannah Carlson’s new book Pockets: An Intimate History of How We Keep Things Close is such an engaging read. Carlson — who teaches at the Rhode Island School of Design — draws from sartorial history, design theory and art and literature to create an engaging cultural history about pockets and the people who use them.

InsideHook talked with Carlson about the genesis of her book, the unexpected places her research took her and how both Walt Whitman and Virgil Abloh factored into her work.

InsideHook: What initially inspired you to write a book about pockets?

Hannah Carlson: There are two answers to that. One is just the typical annoyance about not having enough pockets — that gesture that you make when you are locked out of the car or your apartment, and you do the patting yourself down over the chest thing and you think, “Oh, that gesture is so reflexive.” It really suggests that our expectation is that we should have objects at our side. Why does women’s wear so often fall down on the job?

I think the other and more important ancillary to that is that I happened to be teaching a class on Robinson Crusoe and all the subsequent literature on castaways. There’s a famous scene that was infamous in the 1720s. It was Defoe’s Notorious Blunder, and it was all about how pockets are so dependable. We expect them so much that you could, in fact, strip to go skinny-dipping and leave your clothes on the beach, but still expect to have your pockets at your side.

There’s this amazing scene where Robinson Crusoe arrives on his island, shipwrecked. He realizes there’s no hope. He has nothing on him but a pocketknife, some tobacco in a box and a tobacco pipe. He thinks he’s finished. The next morning, he wakes up and he sees that his ship is foundering just offshore, so he strips his clothes, swims to the boat and is so excited to find all this useful stuff. Then he stuffs his pockets full of food and rations and swims back to shore.

It was the talk of the town. People talked about it for years, his notorious blunder — that famous passage of him swimming to shore naked with his pockets full of biscuits. Pockets come up all over in literature, or any description of how somebody moves through the world. Eventually, there’s going to be some discussion of pockets.

Jonathan Swift and Samuel Beckett both play memorable roles in the book, which I appreciated.

I was wondering if anyone would pick up on that Beckett reference. I think it’s really fun.

In Pockets, you write about how clothing and gender relate — and have related — in the Western world for centuries. How much of that was information that you expected to find when you began working on this project?

A lot of it was unexpected. One thing I was surprised about was this question about how important gender is [to clothing]. We think it’s recent, it’s a social media phenomenon, women expressing being upset over lack of pockets. I was really surprised to find that, a century ago, suffragists and women’s rights advocates were also talking about the issue.

That came up when I was doing database research, and looking through newspapers and journals. There was just a ton of stuff about suffragists not only wanting to vote, but wanting pockets. That whole conversation was very surprising. Suffragists called the handbag a badge of servitude, and the anti-suffragists get really mad and said, “Neither pockets nor the vote is a natural right.” That whole conversation was fun to explore, but also very surprising.

Were you primarily working with historical newspapers and magazines? Or were there specific archives that you turned to to research this book?

I did a lot of archival research in museums; I went and looked at a lot of pockets. I found when you actually look at clothes themselves, you find interesting clues. For an 18th century court coat, you just see the image and you think, “Oh yeah, it has some hip pockets.” But when you actually go inside, some of those pockets actually had multiple compartments within them. They were accordion-shaped so that you could further differentiate your stuff.

When I looked at women’s wear in the 19th century, that was the first time where you have inside pockets at the side of your skirt. They were shaped exactly like an earlier kind of pocket, a tie-on pocket, which was sort of shaped like a tear shape.

Looking at objects is really important. But the funny thing is that I looked at so much that the rest of it was pretty archival: etiquette books, satires, prints and novels. It just ran the gamut.

Did you see anything that suggested that someone, in coming up with a menswear design in the 20th or 21st century, had kind of seen something much older and thought, “I’m going to try to update that for the present day?”

Menswear in particular has such a fascination with military pockets and sportswear pockets, and I think we’ve seen that all over the place. It gets put on leisurewear, but also those pockets come back and decorate fashion today. I mean, there are great coats where some of the pocketing has become baroque. And I really do think that that is a 20th century military sportswear interest.

In Pockets, you bring up some designers who have taken the use of pockets to sort of signify something being leisurewear versus businesswear, and the way that that has become blurred in more recent years. I was wondering if you could you could you talk about that a little bit?

I spent a lot of time looking at GQ. And GQ from earlier in the 20th century is a riot from our point of view. It seems as though they’re almost like acting like an etiquette guide, and menswear had such a narrow parameter for what was correct. And in the ’50s, GQ or Esquire is saying things like, “Pay attention! Don’t wear that pocket. That is for sportswear, not the office.”

So there’s all this advice that mentions pockets and how a patch pocket that’s visible is for leisurewear. Some of these writers suggested defensively that pockets are one of the few exclusive prerogatives of apparel left to us by the ladies. So if you want to be sort of rugged, you might want to wear something that was more borrowed from the leisurewear sort of realm.

I think the casual revolution occurs after World War II, and the notion that no one wants to go back into a three-piece suit, and that there should be more options for menswear, really starts to take hold at that moment. I argue that some of that sense of casual ruggedness and derring-do is because menswear borrows from that continuum of the military and sportswear because in World War II, we got this new kind of uniform. That uniform was the M1943 combat jacket, and it was cotton, not wool. It was blousey, it wasn’t tailored to the body.

One thing that military designers figured out was that really big bellows pockets that you could stuff full of grenades and rations and other weaponry was really useful in World War II, because World War II was a mobile war. The troop commanders witnessing tests of these new uniforms reported that, “The discovery that men could fight out of their jacket and trouser pockets was the most important feature of this new battle uniform.”

I’m theorizing that some of that sense of ruggedness plays out later in the 20th century, when we get all this borrowing: cargo pockets, zippered, buttoned. All that kind of functional-looking gear suggests, “I can pull this off, I’m ready for business.”

Early in the book you featured a Bernard Rudofsky diagram about the concept of excess pocketing, which is both hilarious and a memorable image. How did you find that?

In 2018, MoMA had a retrospective, it was called Items: Is Fashion Modern?, and they were looking back to a 1944 exhibition. Rudofsky was an architect, and I think he proposed an architectural exhibition that they rejected. They said, “No, do something else.” And so he said, “I want to do an exhibition on clothes. And I want to show you how irrational modern fashion is.”

That was typical of architects demeaning fashion, because it was so changeable. It was about whims, it wasn’t about functionality. And so he has this whole exhibition about how crazy modern fashions are, how we think that they’re rational, but they’re not actually. He really went after menswear, and he thinks tailoring is wasteful, that we waste all this fabric, there’s all this time to make it and that we should really sort of go back to cloth itself. He’s suggesting that we wear really simple togas, basically.

And he’s arguing along the lines of: Look how many pockets there are. Nobody could actually use those pockets. You couldn’t find anything. And also, fashion decrees that you shouldn’t have all this lumpy stuff anyway. He basically wants to say it’s pointless. But it’s so fun, and I just love that image.

It’s interesting to contrast that moment in design history with the work that Virgil Abloh — who you bring up in Pockets — and others were and are doing to bridge disciplines in a way that would have been inconceivable decades ago.

Menswear is undergoing a revolution — and it’s just so expressive. Abloh was clear about that, that you could enliven menswear in all sorts of ways. In the book, I reference the hot pink suit he designed that has these bellows pockets on it. There’s this wonderful tension in the way color has come back into menswear in this exuberant way. He’s mixing that color with really functional attributes.

A New Book Revisits the Impeccable Style of Paul Newman

Talking with James Clarke, author of “Paul Newman: Blue-Eyed Cool”In Pockets, you have those two amazing photos of Walt Whitman and W.E.B. Dubois, each with their hands in their pockets. I’ve always thought of both of them as very much men of their time. And in both of those photos, they look like people who I might see walking down the street in New York. That reshaped what I thought of both of them, which was pretty fascinating.

That was one of my favorite chapters. We think of pockets as something that carry useful stuff. But really, one of the most contentious objects that pockets have carried are our hands. It’s considered rude to hold your hands in your pockets. Pockets are in and around the erogenous zones, according to the poet Harold Nemerov. And so there have been these centuries of injunctions not to put your hands in your pocket.

But men very early figured out that it’s really sexy to break the rules — and that walking around your hands in your pockets just looks cool. Part of that, I think, is that there’s always this tension in fashion. Fashion wants to be subversive. And it wants to show up how ridiculous the idea of good manners is. So fashion is always kind of breaking the rules.

The other thing that I think is amazing about that gesture is that when you have your hands in your pockets, you’re not using them to talk to people and suggest that you’re engaged with them. We interpret that as the person removing themselves from some sort of social interaction. It’s cool because it’s withholding. It’s metaphorical, my hand is in my pocket, that means I’m not even going to interact with you.

They’re what in the 18th and 19th century was bad manners, but also cool in the sense of this modern 20th century gesture. And I think it’s because of that sense of the mix of sexuality and remove coming together in this way that can’t really be beat.

Was there anything that you found while researching the book that you kind of weren’t able to fit into the confines of the book but was still really difficult to cut?

One thing I adored was, I did a whole kangaroo thing. Our human jealousy over marsupial endowment runs as a theme throughout the book. Thomas Carlyle was the first guy to write a book about pockets. His book The Tailor Re-tailored [otherwise known as Sartor Resartus. -ed.], he was thinking about the social meaning of clothes. He writes that we don’t wear clothes because we’re ashamed of being naked. We wear clothes because without clothes, there wouldn’t be pockets. We are not marsupial mammals, we need tools to act and do.

I found some imagery of early marsupials and kangaroos. And it turns out that Europe and the West only found out about kangaroos when Captain Cook arrived in New South Wales and reported on his discoveries.

What I didn’t include is that in New South Wales, the first printed image of a kangaroo is in a book reported to be written by the “prince of pickpockets,” George Barrington. The first European printed image of the kangaroo that featured her pouch appeared in a book that’s attributed to him. He was an infamous pickpocket, and he was banished for his crimes to the penal colony of New South Wales, where he soon embraced reform.

Kangaroos are depicted as this animal who has this thing that we’re really jealous of, which is a pouch that always travels with us. I feel like I could have gone way down the rabbit hole. Sorry, that’s a mixed metaphor. I could have gone farther into this notion of our jealousy over pockets and this amiable creature, the kangaroo, who has something that we’re jealous about. I didn’t include the most famous pickpocket, but I love that he’s the first guy with a book that describes this creature.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.