Does the future of humanity involve living in outer space? Plenty of movies, television shows, tech magnates and governments have answered that with a resounding “Yes!” As for writers Kelly and Zach Weinersmith — well, they’re not so sure.

The Weinersmiths are the authors of a new book, A City on Mars: Can We Settle Space, Should We Settle Space, and Have We Really Thought This Through? As the subtitle indicates, they take a somewhat more skeptical approach to questions of living in space, from exploring the very real health risks of spending extended periods of time traveling through the solar system to pondering the logistical challenges of establishing a permanent settlement on another world. And that’s before they get to the question of space cannibalism.

InsideHook spoke with the Weinersmiths about the origins of their project, the surreal directions their research went in and the bizarre ways different space programs test potential astronauts. (Hint: skydiving plays a role.)

InsideHook: What first drew both of you to writing about these questions of people living in space? Was it something that had come up in a previous project? Was it because of pop culture depictions of humanity living in space? Or was it something totally different?

Kelly Weinersmith: We wrote a book together called Soonish. And when we were working on that book, there was a chapter on cheap access to space and another chapter on asteroid mining. For the cheap access to space chapter, the cost of going or sending stuff to space was going down so fast. And then we were reading about how asteroid mining is going to give us the resources that we need to build these space habitats.

To be honest, we thought that maybe space settlements were not that far off. We were kind of excited about writing about things like, what should we expect in the next decade? And how long will it take before we get 100 people up there — and 1,000? And then we did four years of research and we realized that those are not all the problems, that we need a lot more than being able to ship mass to space and knowing that there are resources out there.

Our book went from a “Yay, space settlements are coming soon!” angle to a “Here’s the stuff we still need to figure out before space settlements can be done safely and ethically” angle.

There are a growing number of depictions of space colonization in pop culture. As people who have done some research into this, are there works of science fiction that are getting this right? Are there writers who are reckoning with this on the fictional side, as well as the nonfictional side?

KW: I felt like in The Martian, Andy Weir did a pretty good job of getting a lot of the science stuff right. Although I don’t think that he removed perchlorates from the soil before making his potatoes, and that could have killed him. It would have messed up his blood pressure. I like The Expanse, but to be honest, when I’m watching sci-fi, I’m not usually critiquing it so carefully in terms of “Are they getting all the science right?” I’m happy in science fiction if they create a set of rules and then they just abide by them and stay consistent.

Zach Weinersmith: One of the things we did for this book was we read a lot of astronaut memoirs. And the thing to know about astronaut memoirs is they are, almost without exception, incredibly boring.

KW: So boring.

ZW: Because actual life in space, and this will be true in a more advanced future, is day-to-day stuff. A lot of what you do if you’re on the [International Space Station] is you scrub some mold, you check the toilet, you do a call home. You are in space, but most of your work is the kind of work you’d have to do back home.

So typically, in sci-fi, what you have to do is introduce an additional element, like some rare resource that’s there, like helium-3. We argue, I think quite convincingly, that you should be skeptical of any claims about helium-3 being a great value. But science fiction usually has to introduce an element like “unobtainium” in order to justify going across the universe, or even somewhere relatively close by. So it’s not fair to critique that, because you have to tell a story. There has to be some reason to be there and doing stuff.

Astronaut memoirs are very similar to memoirs of life in Antarctica or aboard submarines. They’re just not that interesting, except for a few quirky details, but not day-to-day life.

KW: Unless they’re good authors. Simply being there, the story is not enough. You have to also be clever.

ZW: There’s a tiny number of good memoirs written by people who are just objectively good writers, but that’s it.

In A City on Mars, you wrote about the role that Starlink satellites have played in the war between Ukraine and Russia. As you were writing the book, were there a number of things that came up in the news that echoed your points or expanded the scope of the book as you were researching and writing it?

ZW: That would actually be one of the top examples, I would say. We did try to write the book so that it would still be useful even if the environment changed a lot, because a lot of this stuff is deep aspects of international law. The Ukraine thing is interesting partially from an international law perspective. We were just writing something about how it’s come out now that there were negotiations between countries and Elon Musk, which is a really strange state of affairs — although it is now fairly normalized, is my understanding. So international law did eventually win.

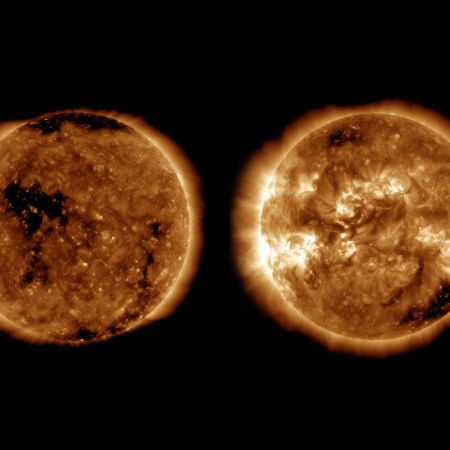

KW: The Artemis Accords came out while we were writing. And then a National Academy of Sciences report came out about space radiation, where they pretty much said that space radiation on a trip to Mars is going to way exceed what we’re comfortable with, so we’re going to have to have the astronauts sign waivers that say, “I get it, I might die.” There were a couple of really interesting scientific papers that came out and some international law stuff that happened while we were writing.

ZW: I would say that in recent space history, the big thing is reusable rockets and SpaceX. But that was before our book.

What’s Lost When Robots Replace Astronauts

Questions of money, technology and risk aversion have kept humans from venturing beyond the moon. Will space exploration now be left to machines?As you explain in the book, you each have very specific skill sets. What was the process like as far as putting everything together and then coming up with the version of the manuscript that we see with the illustrations, with the hypotheticals, with the case studies and everything else like that?

ZW: Our last book was a much easier book to research. It probably had about 5% as much research as this one. This was an insane research project. We ended up having a lot more division of labor to sort of play to our own strengths. So our joke was, I read more quickly, but understand with 90% comprehension. Kelly reads more slowly and understands with 100% comprehension.

I did a lot of the lighter stuff. I read a lot of memoirs. I read a lot of future casting books from the past about space. Kelly will read NASA’s horrifying 150 pages of technical details on space radiation. And then what we do is, we both take notes on a lot of books. We tried very hard to go to the original sources. So, for example, in international law, you could just read about space law. If you do that, you’re apt to miss a lot of things. So we have a chapter on whether you can create a state in space. If you only read space law, you’re missing a lot. You have to actually read the horribly detailed books on how state creation works in the post-World War I era.

We would take these vast amounts of notes and then Kelly would condense them into what we would call the dossier, which would be a 40-page writeup of what we know with a stab at organization. And then I would try to cut that down to a human-friendly size and organization. Then after that, there was kind of a spit polish with making sure the sentences read well and adding jokes and illustrations. But really, the primary research came first. The funny and the goofy stuff was the very last little step.

Scattered throughout the book, there are some absolutely fascinating pieces of information. One of the things I noticed — and this gave me a panic attack when I read it — was the detail about the Russian or Soviet space program giving candidates puzzles to solve on their wrists while they were skydiving.

ZW: To be clear, that’s a little fun tidbit. I don’t know how much it matters in space, but it was so good we had to put it in. There’s this monster book called something like Space Safety, and it was this complete write-up on medical matters. It’s like everything from on-the-ground training to psychiatric care to selection processes to bone health.

A big part of how you avoid problems in space is by first not having them on Earth. So the selection process is pretty stringent. If you have health problems, unless you are a millionaire, it’s pretty hard to go to space. Our impression was, if you look at the different programs, they’re all kind of after the same sort of thing. You want people who are pretty mellow, who focus on details — the kind of person who can read a thousand-page manual and tell you stuff from it later in case something goes wrong. High-competency boring people are the ideal astronaut type.

But within that, the different agencies have their own funky stuff that’s cultural and varies between nations. And one of them was there’s this test where, at least according to this book, they would drop you out of a plane in Russia and you had a little puzzle on your wrist where you match up colors and numbers and you have 60 seconds of free fall in which to solve the answer. I guess you write it down on your wrist or something. I don’t know if this actually helps with selection, but it is kind of awesome.

KW: For JAXA, the Japanese space program, you have to make something like 1,000 origami cranes. The idea is that you have to be able to continue to do things with high skill, even if they’re boring, over and over and over again. But I would rather do that than jump out of the plane for the Russian program.

What really freaks me out is for the U.S. program, they put you in a pretty tight, dark space and they don’t tell you when they’re coming back to get you. I would panic, as a claustrophobic person, but apparently the people who make it into the Astronaut Corps take a nap.

ZW: I didn’t know that they still do that.

KW: They did at one point. I thought Mike Massimino fell asleep in it. There are so many parallels between the Navy and space. I’ve got a friend in the Navy and he said, “As a hazing ritual, they lock you in one of the torpedo tubes and they don’t let you know when you’re coming out.” I’d just die.

You also brought up the way that Armenian cognac was, for a while, the go-to booze that astronauts and cosmonauts drank. Do you have any more insight on why that particular type of alcohol was so in-demand?

ZW: Our source on that was a wonderful book called Alcohol in Space by Chris Carberry. He did a really good job. And it’s very thorough.

Every time someone talked about smell in an astronaut memoir, we compiled that. All of this information is scattered, and it’s similar with alcohol. If you read a lot of memoirs, there’ll be a sentence about what they drank on the spaceship. And so Carberry actually did that — he found everything.

I should clarify, it’s not their go-to alcohol. It’s the ideal alcohol. It was the alcohol of choice. I don’t know that it was like the maximum amount, because whiskey and vodka were reported, although I should say there’s no report we ever heard of people drinking to excess or doing bad stuff as a result of that.

I think for some of this stuff, as an American, you think, “Oh my God, they had whiskey.” But in other cultures, it’s like, well, of course, you had a shot after dinner.

KW: Well, I mean, on [the] Mir [space staion], there are times when the oxygen or the oxygen canisters are catching fire. You want to have a sip of cognac after that; you need to relax somehow.

ZW: But I don’t know if he went into why Armenian cognac is considered the best. I don’t know that I’ve ever tried it, actually.

A sizable chunk of the book is focused on how space law will work. Did you have a sense going into the project that it would make up as much of the book as it does?

KW: We knew that we were going to devote a fair bit of space to it. In our book Soonish, we talked about some laws that the Americans were writing up that were saying that our interpretation of international law is that it is okay to extract and sell resources. We knew that that wasn’t agreed upon by all nations and that was a potential source of conflict. But the more we dug into it, the more nervous it made us and the more unclear it was whether or not you could actually have nations in space, as all these people are claiming you can, like Musk and [Robert] Zubrin. So if you had asked me how many pages we would devote to space law, I probably would have guessed 50 pages instead of 150 or whatever. But I found it very interesting in the end, but also important.

ZW: I would add to that, too, that part of the discrepancy was that we’d originally envisioned that we would talk about law that was specific to space. We came to feel that if you do that, you’re really missing the big picture, because you could easily get the idea that the Outer Space Treaty is a weird law that happened one time when, in fact, it’s totally normal if you compare it to other laws that were established in the 20th century.

KW: Like Antarctica.

ZW: Exactly. I think if you look at how much of the book is specifically about the law of space, it’s probably more or less in line with what we expected. But we didn’t realize how much additional information there was. If you want to know how states can be created, space law just doesn’t count. You can’t read space law to understand how you can create a space country. You have to snap it onto this other long history of how we create states on Earth and when they’re allowed to come into existence and when they’re not. I think the main reason it’s expanded is that we wanted to add how we got here and how it interfaces with the broader international law framework.

KW: I think the space lawyers were thrilled that space law is going to make it into a pop-sci book. We also felt like it was going to be a difficult task to do well. We tried to read really broadly about Antarctica — which is how we found that story about the Nazi Sieg-Heiling a penguin. We tried to add as much fun stuff in there. It’s a lot to ask readers to read that much about law, but we tried to make it funny.

Are there entire firms that are dedicated to space law? Is it more a case of lawyers working for NASA or Space Force or something similar?

KW: It’s pretty big. I mean, there are a lot of academics who study space law, but then there are also a lot of people who do space law. But mostly what they do is things like insurance for satellites: who’s at fault if your satellite breaks into pieces and a bit of it hits another satellite? Right now, a lot of it is for the emerging low-Earth-orbit economy, and law pertaining to that.

At the International Astronautical Congress, there are big sections on space law where they come together to discuss things like how you interpret the Outer Space Treaty. So it’s a big thing, I think.

ZW: Yeah, there are space law moot courts for students. It’s non-trivial. It’s a pretty big field of study. There are multiple textbooks and centers and things.

KW: But I have to say, “space lawyer” does still sound like a job that should only exist in a sci-fi novel.

ZW: They should be called that. I don’t think they call themselves space lawyers. They would say something like “international law scholar with expertise in space.” There is a book called Space Lawyer. We read it, but that was unusual.

KW: But that was fiction.

ZW: Bad, bad fiction.

Astronaut Chris Hadfield Takes to the Skies With Cold War Thriller “The Defector”

It’s an absorbing blend of history and fictionAs someone who was on my high school’s mock trial team many years ago, I think it would have blown my mind if we’d had a case set in space.

ZW: It is kind of amazing the extent to which you could say that the rules we have for what goes on on the Moon in some sense go back to what the Romans were doing 2,000 years ago vis-a-vis fishing. It’s kind of astonishing, the through lines.

Actually, we got to talk about this. I kind of understand, but why aren’t more young people excited about going to international law? It’s one of the few places where you can study and write down stuff. And it has these huge effects, if your ideas get any kind of traction.

I would be remiss if I did not ask about space cannibalism.

KW: Is there a specific question? Because if you let us go, we’ll talk for hours.

Did you have a sense from the outset that this was going to be something you would have to address? And you wrote about this incredibly horrifyingly detailed academic paper on space cannibalism. How did you find that? And why was it so terrifying?

KW: I’ll address that part and then Zach can talk more broadly about our way into space cannibalism. So Erik Seedhouse, the author of that book, his goal was to write an entire bookshelf of books on space. And he has done that. He’s written a lot of books on different aspects of space travel and space tourism.

This book was specifically about analogs between polar expeditions and life on Mars. And unfortunately, in some polar expeditions, things went poorly and the only available food was your crewmates when they passed away. But he seemed really fixated on it. As I was going through it, I thought, gosh, you’re really not talking about the vast literature on psychology and isolated and confined environments. It seemed like it was mostly a rant by this incredibly fit guy about — he told you that he’s a triathlete, so somehow it was very important in this book that, you know, he’s mostly dark meat.

He was complaining about how the youth are just not really prepared for trips to Mars. They’re not prepared to make the hard choices and nobody works hard anymore. But then, out of nowhere, after leaving all of these important points behind, he mentions — more than once — this cannibalism thing. I guess I’m willing to go on record saying this was pretty cursory about stuff. I wrote him to follow up on some of the stories to get more details, and he never wrote me back.

The only place in this book, in my opinion, where he gets detailed is when he’s talking about how you could 3D print knives to carve into your crew members.

ZW: Why do you have to print the knives?

KW: I think most of the knives that NASA sends up are pretty dull, so you don’t hurt yourself. I don’t know. Anyway, all I can say is I was just kind of aghast. The margins in my book say, “WTF?!” So those are my thoughts. Don’t bring him with you into space.

ZW: We thought it’d be interesting to have a chapter on death in space. What would you do if someone died in space? And there have been a tiny number of articles written on that question, but they’re just speculative. Our general view of the process was, unless it was incredibly amusing, you didn’t want to get into a topic unless it would actually affect the trajectory of space settlement. So it turns out there’s just not much to say. I think we put in the one fun fact, which is that if you kick your friend out of the airlock and they go into orbit, you have to register them because they’re a satellite now. It would be gauche to not register the corpse you put into space.

KW: So we also talked about Antarctica and the deep-sea bed as ways to govern space. I also went down a rabbit hole for how you govern the International Space Station, because you have people from all these different nations there. It turns out that each module is governed by the country who sent it up. Then we started wondering, if you ate a crew member on the ISS, under which country’s laws would you be prosecuted? We don’t really know how this came about.

ZW: I found one paper by [Robert] Freitas that was just amazing. He’s a nanotech guy. He wrote, I think, an undergrad thesis or something like that on the question of survival homicide in space. It was motivated by this book and movie called Marooned, in which you have three astronauts and something goes wrong and the oxygen supply is going to run out before they can get rescued.

So ”logically,” somebody needs to die so that you can survive. It’s sort of like the Law of the Sea, only it’s in space. And because it’s in space, it adds this extra element of “We know with exact certainty that we will definitely die.” Whereas at sea, maybe you hold out and maybe a boat comes by. Dolphins come by and you get a snack, or it rains or whatever. So he explored this question.

It was nice because we did read other stuff, but he did an up-to-1978 review of the literature on this. And it actually turns out it’s a fairly involved question because there’s this idea called necessity, which is: should the law countenance the idea that you can kill and eat someone if you need to? Because it’s a dangerous thing to say, “Well, if you need to, it’s okay.” But the interesting thing is, it varies by country. And that’s where it gets funny, because the ISS has, so to speak, many kinds of laws that would apply in a scenario like this. It’s questionable.

Was there one fact or moment in history that you learned about when researching this that stood out above all others as being completely shocking or changing the way you’d thought about this subject?

KW: This is a boring moment, but it was a moment that changed my whole opinion about space settlement, and it was when I learned that there’s very little carbon on the Moon, because we’re carbon-based life forms and we need carbon for our plants. And that was the moment where I thought, oh, this is going to be a lot more work than I thought if you need to send up everything you need to make life, to make the Moon work. For me, that was a moment that made me think that maybe it’s been undersold how complicated this is going to be.

ZW: As we were researching law stuff, we also wanted to research geopolitics. There’s a small but serious literature on the politics of outer space. The classic book is by [Walter A.] McDougall. It’s called The Heavens and the Earth. I think it won a Pulitzer [Ed. note: the 1986 Pulitzer Prize for History], but it’s from 1985. It’s a little out of date. But what’s interesting is he goes through in extraordinary detail arguing that it’s not clear [John F.] Kennedy actually cared that much about the space program as an endeavor; he cared about it as a political move.

Once you start to see that, it kind of flips your head on how to view the whole space program, because generally as Americans, we look at Apollo 11, where we landed on the Moon, and very little else. It’s seen as a nationalistic and engineering triumph. But once you see it like that, it was fairly nakedly political.

There’s another great recent book called Operation Moonglow by Teasel Muir-Harmony about exactly how PR was wielded by the U.S., down to taking pieces of space equipment to department stores in Japan to say, “Look how great America is.” There were things we would now probably call focus groups. Part of why that “for all mankind” message came through is because videos were made and shown to non-Americans, and people didn’t like the overly zealous American power angle. There was a push where a high-level government agency wanted to have everybody’s flag out, but Congress said, “Taxpayers are going to be furious at us if we don’t have an American flag when Americans land on the Moon.”

The one other book I would cite is Alexander MacDonald’s. I think he’s still NASA’s chief economist. He wrote a great book called The Long Space Age about how you can take it back further to the building of observatories. A lot of space stuff that is never going to have applications is basically done as a way to demonstrate prestige. In the particular case of sending people to space, it also demonstrates military power because, especially in the early days, it used reused military hardware. To summarize, the idea that most of what we do with humans in space is political really changes how you view the entire project.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.