In a career with drug cartels that lasted nearly two decades, Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía estimates that he smuggled 400,000 kilos of cocaine, ordered at least 150 killings and accumulated a fortune that included a yacht, an art collection with at least two pieces valued at over $500k, a watch collection and $120 million in gold and cash.

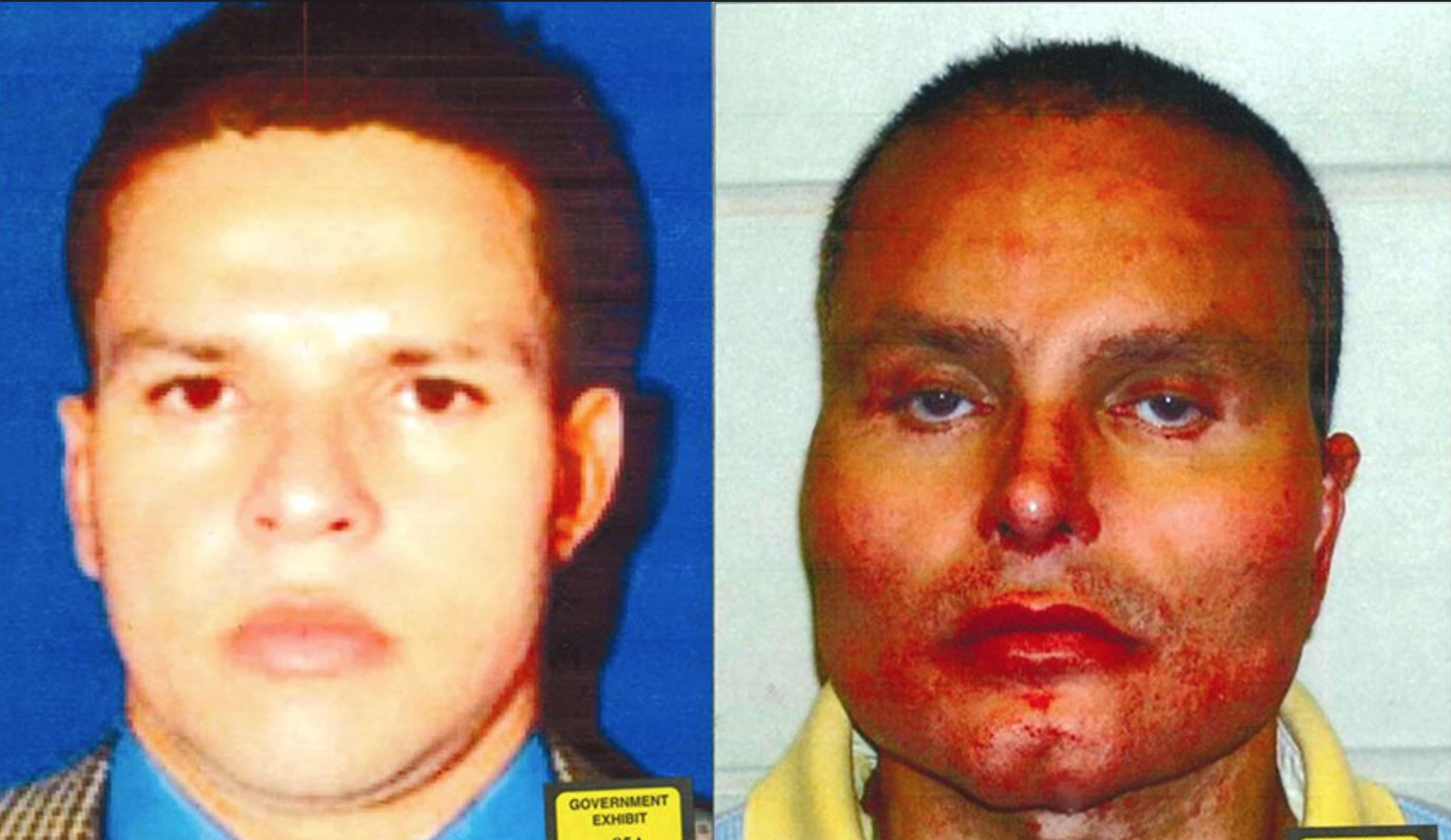

Ramírez, known as Chupeta (or “Lollipop”), was one of the world’s biggest producers of Colombian cocaine as a former leader of the North Valley drug cartel. He is notorious for having changed his face multiple times through plastic surgery in order to evade capture. He also claims to have been the primary supplier to Joaquín Guzmán Loera, or “El Chapo,” who currently sits trial in Brooklyn after pleading not guilty to charges of international drug trafficking, money laundering and conspiracy.

Tuesday marked Ramírez’s third day testifying as a key prosecution witness in the effort to convict Guzman. On the stand, he provided insight and details to his 17-year relationship with the defendant. Ramírez, whose associates would grow and process cocaine to fly or ship to Mexico, called [the partnership] “the central partnership in one of modern history’s most profitable narco-operations.” The government used Ramírez as a witness to strengthen their argument that Guzman, as a leader of the Sinaloa Cartel, smuggled tons of Colombia cocaine into the United States. The defense focused on the lies Chupeta told law enforcement and murders that he ordered to undermine his testimony.

The Beginning

The two kingpins met sometime in 1990 in Mexico City, in the lobby of a hotel, according to Ramírez. It was there that El Chapo, who at the time was new to the drug trade, offered to smuggle 4,000 kilograms of cocaine to Los Angeles from Mexico for 40 percent of the shipment. This was higher than the 37 percent that most Mexican traffickers charged, but Guzmán’s pitch to Ramírez was that he was the “best and he was the quickest.”

At this time, Ramírez was already a leader of the North Valley cartel. According to the Bureau of International Narcotics and Law Enforcement Affairs, “Ramirez-Abadia was one of the most significant cocaine traffickers in Colombia, and operated primarily from the area of Cali, Colombia.” His involvement with drug trafficking started around 1986. In court on Tuesday, Ramírez testified that before he got into the drug trade, he entered the Colombia military with the intent of becoming a lieutenant, but he left and went to school in Miami to study.

“I came to the United States initially to study and with the idea of selling cocaine,” he told the jury. He also went to school in Colombia, where he studied economy and finance.

He continuously presented himself on the stand as a “hands-on” boss, who knew every detail of his business. He told the jury he debriefed his pilots after every run and that he looked over every line of the accounting ledgers the cartel kept. He bribed authorities in Colombia to destroy any criminal records that named him, so that he could stay ahead of the law while running the cartel.

The Testimony

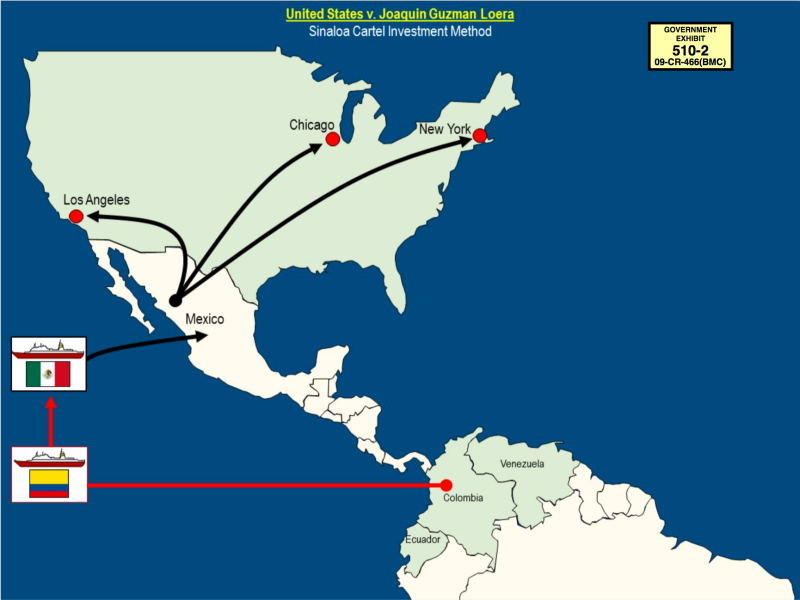

Ramírez and Guzmán originally transferred the cocaine (or as Ramírez said on the stand, “My cocaine”) from Colombia to Mexico by planes, using Guzmán’s secret airstrips. The cocaine shipped to Mexico then made its way to Los Angeles and New York — Ramírez told the jury that “at least 90 percent” of the cocaine ended up in the streets of New York. At this time, Ramírez was selling a kilo of cocaine in the U.S. for about $20,000 to $30,000. In the first shipment — done between Ramírez and Guzmán in 1990 — Guzmán made at least $32 million dollars, Ramirez testified.

But around late 1991, early 1992, the plane shipments stopped working as well, so Ramírez had the idea to switch from the air to the sea. Members of the North Valley Cartel started having covert meetings on the ocean with members of the Sinaloa Cartel, using shrimp and white fishing boats.

The first shipment, made sometime between the end of 1991 and the beginning of 1992, was done with a shrimping boat and contained 10,000 kilos of cocaine. The boats originally met anywhere between 150 and 300 miles away from the Mexican coast, Ramírez explained, because that was naturally where shrimp fishing boats would be seen. But over time, due to security reasons, the meeting place was moved further and further from the coast, with the cartels eventually meeting around 1,000 miles away from land. The boats had secret compartments to hide the cocaine, and often included an area filled with about 20 tons of ice and fish that the cartel bought to hold up appearances of bringing in a catch.

These shipments to the Sinaloa Cartel using boats lasted until about 1998, Ramírez testified. But they were not always successful. Once, according to Ramírez, the captain of a ship carrying 20,000 kilograms of cocaine started sampling the product.

“He started to see ghosts everywhere and American Coast Guard everywhere, and he sunk the ship,” Ramírez said of the captain while in court on Monday.

The leader of the North Valley Cartel immediately flew to Mexico, with the help of that country’s federal police, and got in a helicopter with Guzman to search for the missing drugs.

They only saw vast stretches of the sea. Ramírez said. “When I saw all that sea, I became very sad. I was down. I said, ‘They’re never going to find it.’”

The drugs were found after a year of searching, after divers were hired to look for it.

Another ship carrying 40,000 kilograms of cocaine, worth about $42 million, was hit by a hurricane.

“The boat disappeared, the crew disappeared, everything disappeared,” he said. Guzman told Ramirez he would pay him back for the money lost, and though Guzman was arrested before he paid the sum in full, Ramirez did testify to the fact that he was paid back.

From 1990 to 1996, Ramírez thinks he made as much as $640 million selling his cocaine.

But in 1996, Ramírez turned himself in to authorities in Colombia. He had an arrangement to “turn himself in, dismantle his criminal enterprise” and serve time. However, in court, Ramírez explained that he didn’t do that. Though he was sentenced to 24 years, Ramírez served around four years, two months in prison and did not dismantle his drug trafficking company.

“Because of corruption, I had complete control of the prison,” Ramírez told the jury during the trial on Monday. He explained that he was still making final decisions for the North Valley Cartel even while behind bars.

When Ramírez got out of jail in 2000, he decided to stop sending cocaine to the United States through Mexico. Instead, he was going to sell directly to the Sinaloa Cartel, who could do what they wanted with the product. The cartels continued to use boats, with the shipments nicknamed “Juanita.” The largest Juanita shipment was 12,500 kilos of cocaine.

In 2004, to protect himself from getting caught, and avoid extradition to the United States, Ramírez moved to Venezuela, and then later to Brazil.

“I wanted to be behind a curtain,” he said during court on Monday.

During this time, he still maintained control of his cartel. Juanita shipments eight through 10 did not make it to Mexico, so Ramírez came up with the idea to use submarines to transport about 4,000 or 5,000 kilos of cocaine per trip. They also started to use small aircraft, or seven-piston planes, to transport cocaine.

While in Brazil, Ramírez surgically altered his face to try to avoid detection, including narrowed eyes, a chin lift and severely angled cheekbones. In 2007, Ramírez was caught at a house in Brazil. Due to his multiple plastic surgeries, federal investigators in the U.S. had to confirm his identity with the use of voice recognition technology.

Purpura asked Chupeta about his nickname. “Lollipop, pacifier, what does it mean?”

Chupeta: “In Colombia it’s candy, a bon bon.”

He smiled as he said this. It’s also a play on his sexuality. Chupar means “to suck” Spanish. He was arrested in Braizl w/ his bodybuilder lover.

— Keegan Hamilton (@keegan_hamilton) December 4, 2018

In 2010, he pleaded guilty to murder and drug charges in the United States, where he agreed to become a government witness in major narcotics prosecutions, such as Guzman’s. As part of his extradition agreement with Brazil, he is to serve no more than 30 years. However, there is the possibility that government attorneys can write a letter to a sentencing judge to help him receive less time if they are happy with his cooperation. His cooperation agreement stipulates that he is not allowed to serve less than 25 years.

The Cross-Examination

The details of Chupeta and El Chapo’s alleged arrangement were discussed during the testimony, led by prosecutor Andrea Goldbar. But the cross examination, led by El Chapo’s lawyer Bill Purpura, focused on Chupeta’s history of lying, bribery and murder.

During court on Tuesday, Chupeta admitted he paid $45k to have three people murdered, none of whose names he could remember. Another murder cost him $338,776. That was of a cartel associate’s brother. When asked about the 150 murders that Chupeta’s ledgers show him ordering, he said, “I haven’t counted them.”

He also admitted to ordering multiple murders in the United States. There was a family who was suspected of either stealing from one of his stash houses or informing officials of cartel activity in Fort Lee. Then there was Vladimir Beigelman, in Miss Basin, Brooklyn, in 1993. Purpura brought up another woman, in Queens, who ran one of Chupeta’s stash houses. According to Purpura, she was shot “four times” on Chupeta’s orders. Purpura also suggested that Chupeta killed a former deputy.

Chapo’s lawyers suggested that Chupeta killed his former deputy, Lauriano Renteria, after he was arrested in Colombia. Renteria was the keeper of Chupeta’s secrets. He was poisoned in prison.

“He died,” Chupeta admitted, “and he had a lot of knowledge of my organization.”— Alan Feuer (@alanfeuer) December 4, 2018

Ramirez also admitted to killing 36 family members and close associates of a North Valley cartel leader named Victor Pitiño, who was cooperating after being extradited to the U.S.

After going through all these murders, Purpura showed pictures of documents proving Chupeta had multiple fake identities, such as a Venezuelan passport and ID cards from Argentina and Paraguay. Chupeta did not hide the fact that these were “absolutely lies.” Purpura also brought up the changes Chupeta made to his face, including a hair transplant, lip implants and a nose job.

We also got some new details on Chupeta’s plastic surgery. El Chapo’s lawyer went through a list of his operations:

“Nose altered”

“A piece in your chin — a cleft chin”

“Cheekbones”

“Hair transplant”

“Lip implants”

“Eyes opened up”— Keegan Hamilton (@keegan_hamilton) December 4, 2018

Purpura then asked, “Would you lie to avoid apprehension, arrest, time in prison?”

“At that time of course I lied, I changed my appearance,” Chupeta responded from the stand.

“Would you lie now?” Purpura asked.

“I’m not lying sir,” Chupeta said.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.