We’re way past the debate of what is and isn’t a “hipster.” These days, using the term to describe someone just makes you seem out of it, like a teacher trying to co-opt their students’ vernacular. Now a decade removed from the literary magazine n+1 publishing their seminal investigation on the subject — What Was the Hipster? — it’s fair to say we’re deep into a post-hipster world. Like the yuppies of the 1980s and ’90s before them, the youth of the Bush 2 years are grown up and taking over; in some cases, they’ve reached middle age. Whatever the hipster was, it’s a thing of the past now.

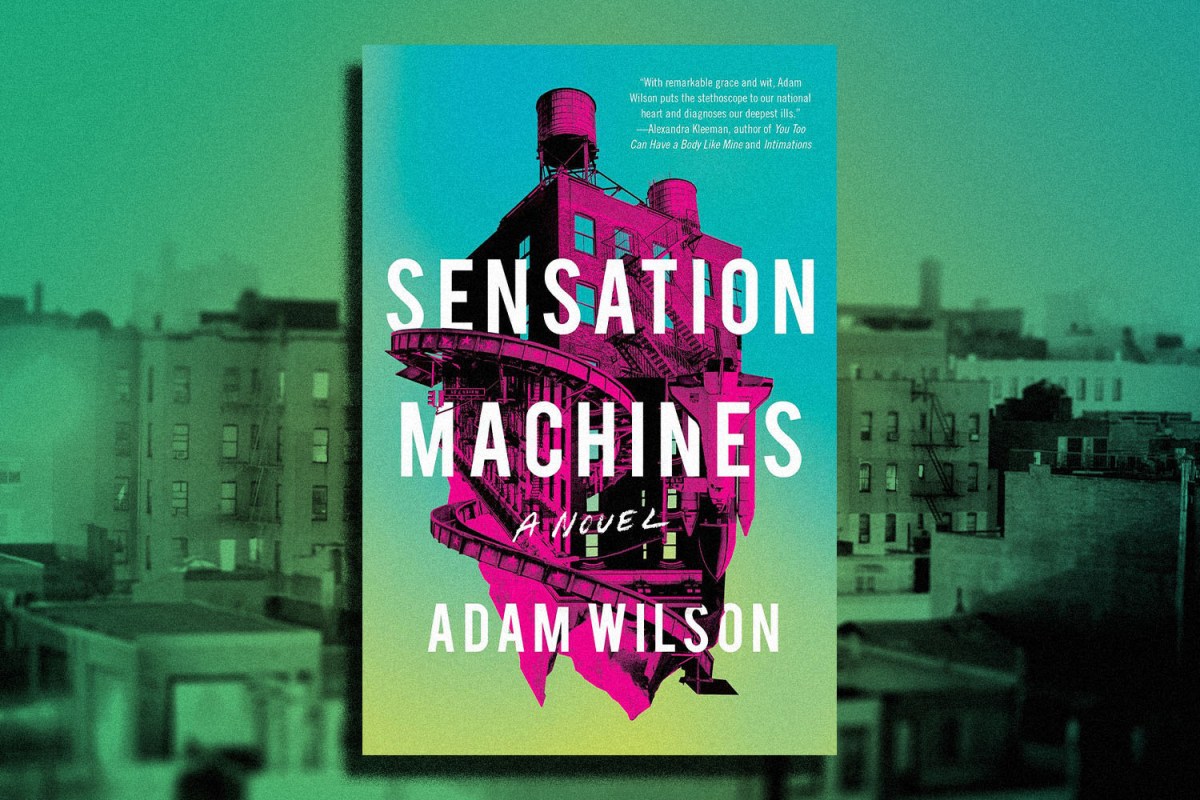

Sensation Machines, the new novel by Adam Wilson, a winner of The Paris Review’s Terry Southern Prize for Humor, isn’t so much a taxonomy of the hipster as it is a straight line from one generation to the next, showing that no matter the era, people grow up and then they sell out. Every generation will have its fun-loving college years, but you can’t outrun age. Many of us will realize — to answer Neil Young’s question — that it’s better to fade away.

But that’s just one layer of Wilson’s brilliant new book. Peel that one away, and it’s a paranoid near-future thriller with a deep swirl of dark humor circling around it. In Michael and Wendy Mixner, we get a couple that feel immediately familiar, and with the plot, we get a time that doesn’t seem too far off. But the events that are set in motion throughout are so bizarre and unsettling that, in 2020, it almost feels like we’re having our fortunes told. Sensation Machines, like works by George Orwell, William Gibson, Octavia E. Butler or Cormac McCarthy, might be labeled “dystopian” because you badly want to believe it can only exist on the page, but deep down, you fear it could easily come true.

While the book might leave you feeling a bit worried for where we’re headed, the good news is that Wilson is a stylist with few contemporaries. He tells a great story and deftly balances light and dark, making you laugh then making you cringe, all while keeping you from wanting to take a break from this new novel.

InsideHook is happy to bring you this excerpt from Sensation Machines, out July 7 on Soho Press. – Jason Diamond, Features Editor, InsideHook

When I arrived at the restaurant, a Greenwich Village sports bar, of all places, the client was already there, in a corner booth, drinking Coca-Cola spiked with rum. I know because I ordered “same as he’s having,” and was surprised to find alcohol in my beverage, and more surprised to find it sweetened by high-fructose corn syrup. I didn’t think that people still drank non-diet soda. At least not in New York.

The client was dressed casually now, in jeans and a bomber jacket. Blond bangs were curtains over his eyes, protecting them from UV rays and admiring glances. His nose and cheekbones were miracles of architecture. Thick, moist lips. Shaven chin–shine. He wore a sober expression one might not expect from someone so boyishly handsome. The effect was jarring; his eyes were oversized, as if they’d outgrown their sockets. I was the subject of his scrutiny.

I’ve always fetishized WASPs. True WASPs, I mean, born in Connecticut and bred on Nantucket schooners eating lobster rolls and deconstructing golf swings. They’ve never shown much interest in me. Rachel Kirshenbaum and I used to drive out to Darien to look in their windows. We loved their orderly homes. The neatly stacked copies of Elle Decor. The calming peach walls.

“I never got your name,” I said.

He nodded. I wasn’t sure he understood I’d meant it as a question.

“So what is it?” I said. “Your name?”

The client sighed as if the answer were obvious. “Lucas,” he said.

Lucas did not read the menu. I wondered if he’d memorized it before my arrival as a power move. If he could reel off the list off the top of his head, wines and specials included. Or perhaps he was the kind of guy who ordered a cheeseburger wherever he went, or else asked the waitress what she recommended and then ordered that. He slurped his drink loudly. The waitress came and we ordered our food.

“Do you have any idea what you’re doing here?” Lucas asked.

“Eating lunch.”

“Good,” he said. “Sharp.”

Lucas reached into his bag and removed a piece of paper. He sketched a female stick figure. He made a click sound with his teeth. The figure had conical breasts, linguini hair. Her eyes were dots. Her mouth was the letter o.

Next, Lucas drew a male stick figure doubled over at the waist. He drew a large phallus protruding from the female figure’s pelvis and extending into the male figure’s rear end.

Lucas wrote Wall Street next to the female figure. He wrote Joe Schmo next to the male. I noticed he wore no wedding ring. I wondered if it was in his pocket, reduced to mere metal among coins and keys. I had no sense of his age.

“Simple story, right?”

“I like that you represented Wall Street with a trans person. That’s very open-minded, if slightly wishful thinking.”

“Artistic license. The point is that what I’ve just drawn is popular opinion, correct? The general consensus, agreed on by communists, and European socialists, and liberals who are afraid to describe themselves as such, and liberals who take pride in the term, and people who call themselves moderates, and people who call themselves apolitical, and Southern rednecks, and gun-toting libertarians, and God-fearing devotees of the Limbaugh radio hour, and the Gen Z mega-demo that’s coming to voting age as the boomers burn and fade. Anyone who’s not a billionaire knows that Wall Street’s the nemesis of our friend Joe Schmo, or Joe Hill, or Joe the Plumber, or Joe Mama, or whatever you want to call someone with a floating-rate mortgage on a depreciating property, and a job that, if it hasn’t already been made redundant, will be sometime in the next ten years. Even you believe in this reductive narrative.”

“My husband works in finance. I know it’s more complicated.”

“I didn’t say you don’t benefit. I didn’t say you can’t argue talking points about the trickle-down effects of corporate wealth or the way markets tend to self-correct, or Thomas Jefferson’s wet dream of an open-air flea market. What I said is that you believe it. In your hidden heart, you know you are complicit in the machinations of neoliberalism. The disenfranchisement of the middle class. The destruction of the working class. You are a scion of privilege. A basic bitch who buys a Rag & Bone dress at full retail, then tells her friends it was marked down. A person who convinces herself that by donating a small, untaxed portion of her yearly salary to Kickstarter campaigns that fund urban farming initiatives, the ultimate balance of her good deeds and destructive behaviors evens out. And yet still deep down, you know that you’re complicit.”

He wasn’t even out of breath.

I said, “These are things I’ve considered.”

“And even though you think hippies are dirty and hipsters are used and discarded douchebags, and homeless teen runaways are a blight on the glory that is Alphabet City, and even though you find fault in certain aspects of #Occupy, you don’t ultimately disagree that the system needs reimagining. So what do you do? You try not to think about it. You stay out of it. You tell your friends that you’re not interested in politics. That you don’t have a deep enough understanding of the situation to form a truly educated opinion. That, yes, your husband is a banker, but he’s a different kind of banker, the good kind of banker. A banker with a heart of gold and a wife of heart, and a Sunday kinda brunch-bloated love.”

“What’s your point?” I said.

“The point is that you’re not alone. There are a lot of people like you. People who were sickened by the camps at the border, and what happened with the pipeline, and what happened in Charleston, and what happened in Orlando, and what happened in Parkland, and what happened in El Paso. People who hashtag believe women, and hashtag me too, and hashtag it might as well be the heat death of the universe, dude, because time’s indubitably up. People in favor of pan-gender bathrooms, an assault weapons ban, a bigger education budget, less military spending, and more attention to climate change. And yet, they’re torn on the UBI because they like their pumpkin-spiced lives. There are a lot of people like you who are waiting for the right person to come along and tell them there’s nothing wrong with the way that they’re living these lives. Do you know the term psychic foreclosure? That’s what people want. A one-size-fits-all system of belief: no gray areas, no tricky ethical quandaries. License to live as you already are. That’s what we’re here to give. We’re here to tell them that just because they went to Wesleyan and smoke fat blunts of Kush and favor a Chinese sweatshop worker’s right to a fair and speedy lunch break, it doesn’t mean they have to go against their own fiscal interests. It doesn’t mean that socialism is the way forward. It doesn’t mean that the toothless meth smokers in Appalachian trailers deserve a percentage of their hard-earned salaries. It doesn’t mean that people like you should pay a six percent property tax on your refurbished brownstone so every bedsore-ridden inbred in southern Ohio can eat chicken-fried cheesecake while watching amateur wrestling on loop. Forget Joe the Plumber. How about Yelena the Trust Funded Yoga Instructor? That’s our demo.”

“Okay.”

I was trying to picture chicken-fried cheesecake. Lucas picked up the pen. He crossed out Wall Street and replaced it with #Occupy. He said, “Your job is to create that narrative.”

“My job is to create that narrative,” I echoed. It’s a tactic I learned early in my career. Repeating other people’s words makes it seem like you understand, that you’re on their side and submissive. “So you work for a bank?”

“No.”

“But someone with an interest in the Senate killing the bill?”

“This is bigger than a bill. It’s about giving people a sense of comfort. You’ve worked with lifestyle brands. Brands that tell people that if they buy a product they can live like the people in the ads. This is the same. We want people to feel like they can be the people they want to be. That they can find peace.”

“You’re a lobbyist?”

“For America.”

“What a line. You chose me because my husband works in finance. You knew I’d be sympathetic.”

“We chose you because you’re good. Your campaign for McDonald’s in India—Eat, Pray, Loving It!” He removed an ice cube from his drink with his fingers. He chewed the ice cube.

“Then why all the secrecy?” I said. “The motel, the project code name, the fact that we haven’t met any of your colleagues.”

“In a week’s time, we’ll be launching a product. It’s a product that I’ve spent years developing, and it’s a product that I believe will change the world. This product is my personal intellectual property, and until it’s ready for the market, I’d prefer that knowledge of it be limited to a small group of trusted associates. My hope is that, within a few days’ time, you will have proved yourself worthy of inclusion in that group. I promise that, if you do, you will not be disappointed.”

“Okay,” I said.

“Now, the success of this product is contingent on the UBI bill dying on the Senate floor. This is where you—your campaign—comes in.”

“Okay,” I said again.

The food arrived. I had a salad. Lucas had a rare cow steak, which cost six dollars more than the stem-cell filet also offered on the menu. He said he always ate real meat, that the kind grown on trees lacked the necessary iron.

We ate quickly. Lucas’s knife scraped loudly across his plate. When the steak was no more, he dabbed the small puddles of blood and grease with his big thumb. He sprinkled salt on his wet thumb. He licked. I put my napkin in my salad and signaled to the service bot. Lucas caught me looking again at his drawing.

“Are you getting it?”

“Everyone’s fucking everyone. That I understand.”

“Good. Because that’s part one of the agenda. Understanding the problem is part one.”

“What’s part two?”

“Part two is complicated.”

“Why is it complicated?”

“Part two is what you’re gonna do about it.”

“What are we going to do about it?”

Lucas reached back into his bag and removed a rolled-up poster. He watched as I unrolled it. The poster featured a black-and-white photo of steel gates beneath a German sign. I’d seen this image before, in person, on a visit to Poland to see where my grandparents’ cousins had been murdered. Over the image, lay an English translation. Whoever designed it had added a hashtag:

#WORKWILLSETYOUFREE

“This,” Lucas said, “is our campaign.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.