Meditate on the word ‘timeless’ for long enough and its literal meaning will start to trip you out. For something to truly be ‘time-less’’, it also must exist independent of the very construct of time, impervious to time’s fleeting nature and able to consider the past, present, and future all in the now.

This reframing of a word we’ve all heard, as explained to me by a multi-instrumentalist several years ago, has come to shape my understanding of all that we call “classic”. It’s also what prompted me to check out The Rubin Museum’s first new exhibit of 2018, a year wherein the institution has dedicated programming entirely to the theme of “future.”

The first such exhibition, The Second Buddha: Master of Time, opened Friday at the Chelsea museum, kicking off an exploration of this theme with some foundational Tibetan Buddhist wisdom about what it means to project your teachings into the future. Spirituality aside, the exhibit has much to say about making art that stands the test of time and leaves us searching for meaning still.

Incorporating dramatic, motion-activated lit paintings, narrative portraits, and augmented reality revealing hidden “treasure teachings” in the art, the exhibit explores the mythical Second Buddha Padmasambhava, the venerable tantric magician and de-facto Merlin of the Himalayas, who legend says could comprehend time’s past, present and future all at once.

“His historical and biographical literature is so vast, but he still remains very enigmatic because scholars are not entirely sure that he actually existed in the 8th century Tibet,” curator Elena Pakhoutova told a preview group of members as I stumbled out of the elevator with more questions than answers.

Gift of Shelley and Donald Rubin.)

Whether or not the 8th Century Buddhist master actually existed at all is up for debate, although it also doesn’t matter. After the empire collapsed in the 10th Century, Tibetans were in a period of fragmentation that made it difficult for them to understand who they were. The mythical origin story of a magician who spread Buddhism amongst the people went a long way toward healing an unifying the country.

“They wanted to bring back the glorious days of the empire, and this image of the enlightened master who was aiding the king to change the land and the people of that land is very similar to the role that Merlin played in King Arthur,” explained Pakhoutova. “I call Padmasambhava the Himalayan Merlin. Just like Merlin, Padmasambhava is timeless. And the stories about him just keep coming back.”

His origin story is illustrated through a 17th Century gilded copper sculpture at the start of the exhibit. It depicts Padmasambhava wearing the garment of an Indian king that the king had given Padmasambhava after his magic tantric abilities were revealed. While Padmasambhava was practicing his magic in the forest, the king’s daughter becomes one of his disciples, and the king wasn’t too psyched about it. Though the king burned Padmasambhava at the stake, he didn’t die, but re-emerged on a lotus to earn his name, which translates to “The Lotus Born.”

Behind the sculpture, a large 18th Century mural acts as a narrative biography depicting scenes from Padmasambhava’s life subduing local spirits and gods in Tibet who were resisting the introduction of this new and foreign faith from India, what we now call Buddhism. Among the scenes is the construction of the first Tibetan monastery, Samye.After the exhibit’s first section, things start to get a bit crazier with a video piece explaining the difference between how time is understood by an average person, an astrophysicist, and a Buddhist. It explains how to an average human, time means that the past is in the past, the present is now, the future is in the future—it all goes in one direction. In the astrophysicist’s view, though, time and space are not considered as separate entities but one in the same. Hence, time is also relative. The speed of motion in space, for example, affects the passage of time and reminds the astrophysicist that it is not absolute, as it slows down or speeds up depending on what we’re doing.

The Buddhist perspective, meanwhile, gives larger context to the show and The Rubin’s intentions with this theme of “future”. In the Buddhist perspective, the past, present and future are absolutely interrelated. Those ideas of time that the astrophysicist has only an intellectual understanding of, the Buddhist can put into practice.

“If I am an enlightened person I see every moment as it really is — as both distinct and part of a whole dimension of time,” says the video’s narrator. “Instead of passively experiencing time, I am able to actively engage with it. The Buddhist master Padmasambhava…could comprehend time all at once. What to us would seem like a prediction or prophecy for him would be a simple observation or fact.”

The curator Pakhoutova summed up the practical applications of this enlightened state in a question— “How do I understand the past, manage my present, and enable my future?”

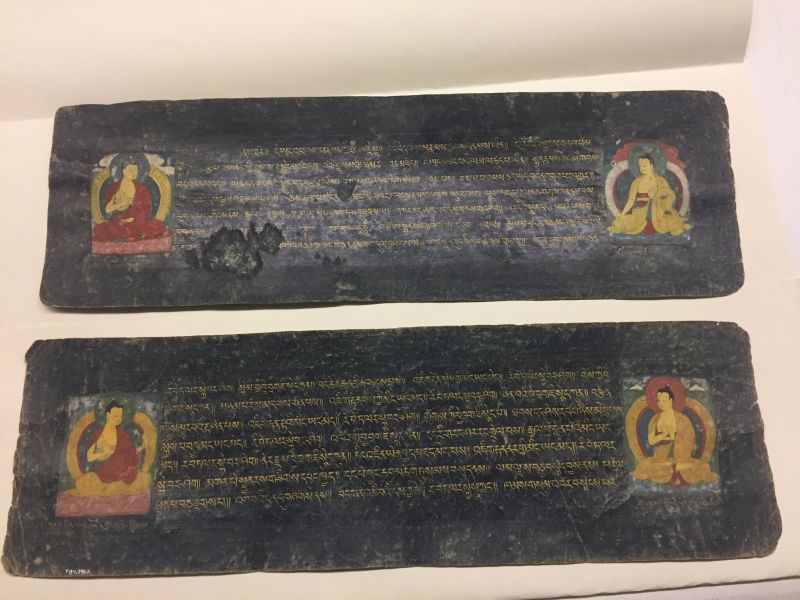

Padmasambhava’s disciples accomplished this by projecting his treasure teachings, or termas, into the future through art. “One of his most important contributions toward continuity and sustainability of Buddha’s teachings in Tibet was this tradition of termas,” said Pakhoutova. “The legends about his life say that he went all over the Himalayan areas and concealed these teachings— sometimes as physical objects, sometimes as sculptures, pieces of text, or sometimes as memories and experiences in the minds of his direct disciples—to be revealed when the time was right.”

As I held an iPad up to a 19th Century portrait of teacher and treasure revealer Jatson Nyingopo, the fiery wheel surrounding him lit up on the screen, explaining a key component of his termas that was only subtly implied at with the visuals. Another tablet illuminated the 18th Century portrait of teacher and treasure revealer Terdag Lingpa to point out his two most beloved disciples along with a hidden poem, written on the back of the cloth, that his students didn’t discover until many years later.

This technology is tastefully noninvasive in ‘The Second Buddha,’ and complementary to its subject. Be it through the AR explaining treasure teachings or the motion-sensitive portrait lighting illuminating details of the 18th Century painting of the deities in the bardo from The Tibetan Book of the Dead, the exhibit treads a respectful line between past and future that successfully invites visitors deeper into understanding the mystical esotericism of Padmasambhava’ powers over time.

Through this tech, the exhibit conveys how the treasure revealers would discover hidden teachings of Padmasambhava, translate them, teach them, and then re-conceal them for a new generation of students to find. I couldn’t help but think of two legends we lost recently, Leonard Cohen and David Bowie, who both studied Buddhism and both seemed to foresee their imminent deaths through the art that they left us with.

Bowie planned the release of ★ for his 69th birthday, knowing that he was terminally ill of liver cancer, and died two days later. Yet even after he passed, the chameleon still surprised us. Expose the ★ vinyl to sunlight and the titular star on the album cover reveals a hidden galaxy. Look at the star field on the inside cover and you may or may not notice that the stars form a constellation of a man. Reflect light off side one to see a bird in flight. Reflect light of side two to reveal a spaceship.

Bowie’s easter eggs were no sacred terma teachings, but with his history of studying Buddhism, it’s hard to think that he wasn’t at least conscious of the way that art can project values into the future.

Leonard Cohen, an ordained Zen Buddhist monk who he passed 19 days after releasing You Want It Darker, likely had similar powers. He prophesied that his end was coming soon in a letter written to his muse, Marianne Ihlen, days before her death. Similarly, You Want It Darker is filled with words of a man who was ready to die, documenting his final exit and making peace with the poet’s artifice as it exists in the future.

In an age when every museum trip is only as significant as the size of its Instagram presence, The Rubin goes to loving lengths to help visitors unplug, slow down and reflect. Just as the museum’s shrine room doubles as a collection Tibetan Buddhist art and a legitimate sacred space complete with prayer cushions, The Second Buddha leaves one with a practical take away about the importance of owning your future, illuminating one of Buddhism’s headiest teachings and presenting it in a manner that’s truly timeless.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.