The fashion industry is so out-there these days, maybe it’s no wonder it took a finance bro from Chicago to knock some sense into men’s apparel.

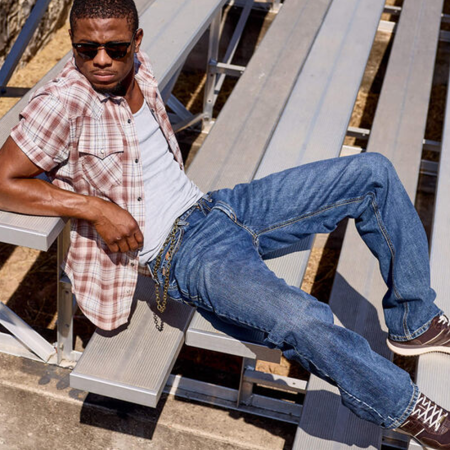

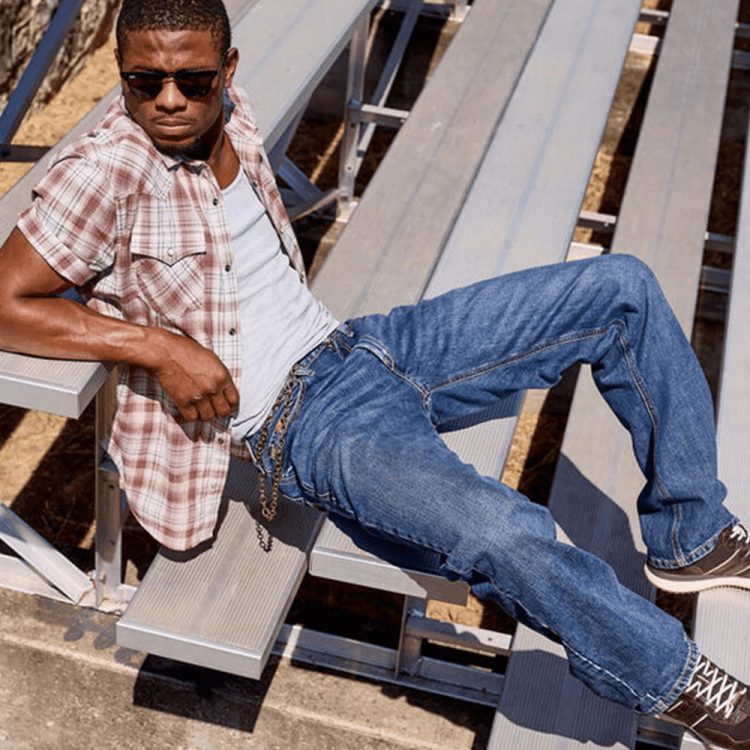

While earning his MBA at Stanford in 2007, Andy Dunn spotted a golden opportunity. His roommate Brian Spaly had been working to create a better-fitting men’s pant: neither too boxy at the hips nor too slim. His big innovation was a curved waistband, which conforms to the natural shape of your waist. The effect is a far more snug and flattering fit, which just so happens to make your butt look better.

“It was a provocative idea,” Dunn told InsideHook. “There has been a lot of evolution in the fit of denim, but not one had really thought of how to apply it to a trouser-cut pant, to your wool dress pants, your khakis, or your corduroy pants.”

Dunn became the cofounder of Bonobos, creating a vision for the brand that was, in many ways, just as innovative as that waistband.

His first stroke of genius was to have the company live entirely online — years before the advent of direct-to-consumer e-commerce brands like Warby Parker and Casper. The rest of the market soon caught on, and imitators swarmed into the space. But Dunn had another trick up the sleeve of his stretch-knit classic oxford. In 2012, Bonobos began opening “guideshops,” or brick-and-mortar stores that don’t actually stock any clothes. (You can try things on and receive your purchases in the mail).

“Everyone says that instant gratification is a critical part of the apparel experience,” Dunn explains. “They’re wrong. Taking your inventory home is not a privilege; it’s a burden. Let us do it for you.”

Bonobos, which now offers everything from formal shirts to athletic wear, now counts 25 guideshops across North America and has plans for another 10 by the end of the year.

Recently, Dunn spoke with InsideHook about his approach to business, shaking up American shopping habits, and the critical start-up trick of balancing confidence and humility.

My parents recently told me they never had more than $12,000 when my older sister and I were growing up. My dad was a U.S. history teacher, and my mom has a classic immigrant story: she was born in a refugee camp in Pakistan and came to the U.S. when she was 20 to send money back home. I had very frugal, hardworking role models. We didn’t have a ton, but we were not wanting for anything.

I wanted to be on the frontline of creating companies, and the best place in the world to go figure that out was Stanford Business School. I felt extremely fortunate when I got in after a summer of backpacking in Southeast Asia. I had a magical two years there: I learned so much and met so many great people, including Brian.

The fashion industry was befuddled. I was trying to built a clothing brand around fit — and do it online. I remember meeting people and saying, “Oh, I’ve got a men’s clothing brand called Bonobos,” and them going, “Where do you sell it? In what stores?” And I would say, “On the Internet.” And I could remember the look of pity in their eyes, like “What a loser!” because the currency in apparel is how many stores you’re in. At that time, there was no Warby Parker, there was no Casper, Gilt Groupe was just coming up, Facebook didn’t have company pages yet, and Instagram didn’t even exist. And here I was telling people I was going to revolutionize everything.

It would not have been possible to approach this as an insider. People in the industry would have said making a better men’s pant wasn’t possible, that the market already had it down. And I don’t think an insider would have been so far-sighted to say, “At some point, e-commerce is going to be the majority of retail. And therefore by building this now, we’re going to be better architects of the future.” Of course, now, being digitally-native has become the way that you create a brand. And then over time, you begin to attract people from the industry to team up with you, and that’s how we’ve really excelled.

Any challenge can feel like an opportunity to fail, but that’s actually a healthy mindset, and it brings a humility to the task. You’ve got to bring confidence — which is “We’re gonna win by doing something that’s never been done before” — together with a real honest intellectual clarity that you could fail for any number of reasons. You’ve got to tip toe between those two competing ideas to build something great.

You want to experiment at just the right level, meaning you don’t want to trip up so bad that you trip up the entire company. When we launched a women’s clothing line called AYR, I quickly realized that building a new brand is really hard. It becomes a management distraction and a capital drain to run both brands when you are still building credibility with the first. It takes your eye off the ball in the core business. Yet they were building something really promising: the women’s denim product was fantastic, Nordstrom picked up the line, and customers were raving about it. So we endeavored to spin it out as an independent company, and we just announced our $5.5 million Series A. It was an extremely taxing process, but we learned a lot from it and ultimately made it a victory.

The future of digitally-native brands won’t be locked up online. They should be a combination of online and brick-and-mortar, but you can radically reconsider what that means, like creating retail stores that don’t have physical stock on hand for take-home. By taking stock out of the store, we were able to put two phenomenal things into the store that no one else can: first, we put in one-on-one customer service so it’s more experiential, almost like an Apple Genius Bar for clothing. And second, by not having to stock the store but online, we can offer a much greater diversity of fit, silhouette, sizing, and color, so you can get a much more personalized combination of fit and style than from any other men’s brand in human history. You couldn’t do stores like this if the brand weren’t digitally native to begin with.

Aspiring entrepreneurs should expect that for the first five years, it’s like raising triplets. You have no time, and no mental bandwidth whatsoever. You are fully dedicated, working 90 hours a week. That’s why the entrepreneurs that I admire the most are the ones who have small kids because they have both a human start-up and a company start-up.

When I came to New York in 2007, there really wasn’t much of an entrepreneurial scene here. Just look at 2016, nine years later, and it’s amazing the ecosystem that’s been created, and now it’s number two after Silicon Valley; it’s just passed Boston. I think over the next ten years, it’s just going to continue to get bigger and bigger. Start-ups are the new finance. I love New York for that.

I’m so inspired by by the can-do spirit and ambition of New York, that you can become great and build something great in New York. The flip side is that New York has tremendous reminders that the world is an unfair place. I pass 20 to 25 homeless people every day on my walk up Sixth Ave., and I try to give as much as I can, but some days I’m just another New Yorker callously walking by. Even so, I think the diversity of the city and the diversity of classes keeps you honest. We’ve got a long way to go as a society and as a country to give everyone access to great opportunity, and that motivates me as well.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.