By all accounts — and by all accounts we mostly mean a good old-fashioned pissing contest between Mssrs. Bezos, Musk and Branson — we are exceeding new boundaries in space exploration.

Over the last decade, there’s been a rapid commercialization of the space industry. For the first time, interstellar exploration has become a collaborative effort between NASA and enterprising private initiatives. But this arms race isn’t just for the good of mankind: these playboys are hoping to find an answer to an expensive inquiry: Is space the next viable frontier for recreational travel? And how close are we really?

Let’s examine.

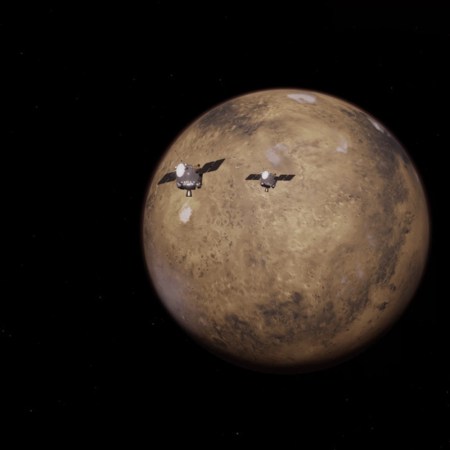

Image via Nasa

What do the tech developments of the new space age involve?

The space-travel industry has splintered into two areas of development: the Space Tourism Industry and the New Space Industry.

The Space Tourism Industry focuses on stratospheric joyrides — all the hype surrounding Virgin Galactic and Blue Origin. Then there’s the New Space Industry: the various aerospace enterprises with ambitions of establishing moon colonies and terraforming Mars — Elon Musk and SpaceX, for example.

The hub of all this inquiry is the International Space Station (ISS): a habitable satellite and research lab orbiting Earth where scientists conduct experiments in biology, physics, astronomy, meteorology and other fields. That’s the destination SpaceX vessels and other competitors are primed to reach first.

Who are the pioneers?

Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk and Paul Allen pretty much underwrite the new Space Age. It began when Scaled Composites and Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen created SpaceShipOne, which successfully launched in space in 2004.

At the top of their needs list: more launch sites, which are also now privatized. Spaceport America is the central launching facility for commercial spaceflight founded in 2006 (with $209 million in public funds) and completed in 2012 to attract the commercial space industry. Branson’s Virgin Galactic is their anchor tenant, along with Musk’s SpaceX.

But the company has experienced a bottleneck in funding, with various delays in space flights because of operational failures. In December of last year, the facility was reportedly vacant, with concerns that public funding had been sucked up in a black hole. New Mexico Senator George K. Muñoz considered selling the operation. It still remains partially financed through contract payload space transportation and tourism-related operations.

Image via Virgin Galactic

Can I go there yet? If not, when?

When things are working, there will be recreational space flights at a suborbital altitude beyond 62 miles of Earth’s atmosphere (which is officially space) in which passengers feel weightlessness for a duration of time before the spacecraft descends back into orbit.

Richard Branson’s Virgin Galactic is the marquee attraction. One of the first aerospace entrepreneurs, Branson predicted he would be flying customers into space by 2007. But a string of failures, including a test flight in Oct. 31, 2014 that injured pilot Peter Siebold and killed co-pilot Michael Alsbury, has halted progress. In February of this year, Branson released VSS Enterprise Unity, but test flights have only reached an altitude of 13 miles, far short of the qualified 62-mile hike.

Billionaire Jeff Bezos has been more of a quiet pilgrim with his vessel, the Blue Origin New Shepard. Although it’s not ready for official launch, the spacecraft has achieved three successful test flights in less than five months. The suborbital capsule projects beyond the 62-mile threshold, which will eventually carry six passengers. But the major setback happened in 2011, when the spacecraft lost a development vehicle near 45,000 feet.

XCOR Aerospace is another quiet player crafting a one-seat prototype, Lynx, also aiming beyond the 62-mile boundary. Once suborbital, Lynx intends customers to feel weightlessness for 4-5 minutes. They’re aiming to be galactic by early 2017. As with their big-name competitors, Lynx funds operations with payload transports to suborbital territories.

Image via SpaceX

Elon Musk’s SpaceX is on a different astronomical plane, with aspirations to bring human habitation to Mars. In the meantime, he has a procession of clients that want to use his Dragon spacecraft to project commercial broadcasting communication satellites, GPS satellites, mapping and science experiments into space. Dragon was the first orbital (beyond suborbital altitude) commercial space vessel to plug into ISS in 2012. In December of last year, SpaceX landed its Falcon 9 rocket on land, and more recently in the middle of the Pacific Ocean after a massive explosion earlier in 2015.

How much does it currently cost?

A ride on Virgin Galactic costs $250,000, while a trip on the one-passenger Lynx currently sells for $150,000.

The biggest focus in the industry right now is to create reusable rockets that can return to Earth without frying upon reentry. SpaceX intends to send an astronaut to the space station for $20m, versus $70m charged by Russia for a seat on a Soyuz rocket. The hope is that space missions will eventually be launched for around $200,000.

Twenty-year NASA veteran Don Thomas, who has traveled on four space shuttle missions, said, “I would think that, in a decade or so, you will see flights to space for $10,000 to $15,000. Space travel will be more in line with an exotic trip to Antarctica.”

And private investors are remarkably bullish on space tourism, which could influence further commercialization and the development of cheaper technologies. According to the consultancy firm The Tauri Group, $1.8 billion was injected into the industry in 2015, nearly twice as much venture capital as it received over the last 15 years combined.

How safe is it though?

Congress gave the industry an eight-year grace period that will apparently keep the Federal Aviation Administration from policing activity and stunting potential growth. But a number of high-profile operational failures have lawmakers nervous.

A recent study found that in U.S. manned space programs, there were 17 fatalities during 732 flights. Or, in other words, 2,320 deaths per 100,000 passengers — 45,000 times more dangerous than flying in a commercial aircraft.

So, TL;DR: it’ll be a while yet before we’re jettisoning into space with cosmic cocktails in hand, but feel free to start practicing your moonwalk.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.