It was an early morning in the Tunisian desert when it dawned on Iheb Triki. Despite the hot, barren location — no source of potable water for miles, which is why he and his friends had packed 100 liters for their trip — there was still enough water in the air to have coated his car and tent with dew overnight. So the question arose: could that natural process be harnessed to make drinking water?

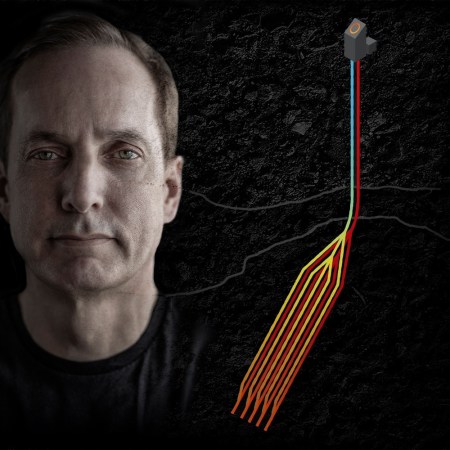

Triki, then working as a private equity investor in renewable energy, discussed the idea with his friend Mohamed Ali Abid, an engineer specializing in motor cooling systems. Within months they built the prototype of a device that did just that: pulling around eight gallons of water a day from the atmosphere, even when it’s extremely dry. Three years of tinkering and fundraising later, they’re now, respectively, CEO and CTO of the company Kumulus, which is busy installing these washing machine-sized devices in schools and factories across northern Africa, the Middle East and southern France, with plans to roll them out to any region where’s there’s a higher need for, and poor supply of, drinking water.

The basic idea behind their device, called the Amphore, is not new. Water condensing from air as the temperature drops is an established property of thermodynamics — “Everyone has seen this happen with the dripping from their air conditioner,” Triki says — and, as he found, three other companies had been working simultaneously on a product that also took advantage of this reaction, all of them making use of high-performance compressor and heat-exchange technology that has been developed only over the last five years. But the Kumulus device is the first to be fully CE certified, the European Union’s safety, health and environmental requirement.

“Largely, regulators around the world just haven’t started looking at water-generation tech yet because it’s too new,” Triki says. Theirs is also the first machine to mineralize the water as it’s produced. Triki argues that mineralization is crucial not just for the health benefit but to encourage people to switch from the bottled water that’s the norm in regions with poor piped water supply. He reckons these differentiators put Kumulus 18 months ahead of competitors. “And that’s an age in technology terms,” he adds.

The company has also recently patented a remote-monitoring system that will allow AI to gather and assess real-time data from multiple machines across a region to both reduce maintenance and then, tracked against weather conditions, fine-tune their performance for the optimal water take.

While this technology sounds increasingly essential as our global need for clean water rises, getting investors on board has not been easy, and the support of the French government for this French-Tunisian startup has been a lifesaver for Kumulus. Triki says if it wasn’t for his background in private equity — “I know how investment works” — he might have given up a long time ago.

“The fact is that investors like software. They don’t like hardware,” he laments. “There’s a long development process. Things go wrong and are hard to fix and there’s the [false] perception that the Chinese can just come in and quickly replicate what you’ve built. And of course, investors just don’t see the value in water anyway.”

“But the Kumulus philosophy is that we want to champion water autonomy — to empower people to be able to live wherever they want because water is there,” he says. ”Water supply is freedom. Provide water and you also provide food — because you need one to grow the other — and in the longer term, hydrogen as a power source. Of course there are many remote parts of the world without water. But it’s remarkable that there are also major cities — Riyadh, for example — where there’s no real water supply.”

Water shortage has become a problem everyone knows about but everyone shies away from addressing.

– Iheb Triki, CEO of Kumulus

Since Kumulus does not rely on seawater or wells — as other proposed water-gathering tech does, with desalination so far hugely energy-intensive and subject to massive losses in water transmission — its device could be a game-changer in many parts of the world. Not for nothing have 40% of Kumulus machines to date been paid for by NGOs; some 4.4 billion people around the world lack access to safe drinking water, by one estimate, and many must travel long distances to get it. The World Economic Forum says that demand for fresh water — only 0.5% of the Earth’s water is fresh — is expected to outstrip supply by 40% by the end of the decade.

“New technology that can take water from the atmosphere is a start, especially in those regions where it’s an impactful option and it’s possible to work with the local community to use it best,” suggests Ernenek Duran, co-CEO of the Montreal-based water campaign group and fundraiser One Drop. “But while it’s not as widely reported as it should be, the water shortage situation around the world is very delicate and that can only be part of wider change.”

![French President Emmanuel Macron with Iheb Triki at a tech conference in 2023 [left]; and the Amphore installed at the Port of Valencia in Spain [right].](https://www.insidehook.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/iheb-triki-emmanuel-macron.jpg?w=1500&resize=1500%2C1000)

Duran argues that while climate change has certainly exacerbated water scarcity, the picture is more complex than the water sector’s typical response of announcing plans to build new or renovate existing — and often hugely leaky — infrastructure. “The bigger problem is that those lucky enough to have access to clean water don’t value it properly,” he says, “and it’s only when you don’t have access that you truly start to value it.”

That, he suggests, will only change both when people in developed nations have the data to make informed decisions — water meters can help here — and, inevitably, when water is priced properly, “as any limited resource is, as gold is,” through legislation if necessary. That needs to apply not just domestically, for a growing global population, but to water’s major users, agriculture and industry, those engines of economic growth.

“We have to find the political will to address this because while people will pay for bottled water — and in those parts of the world where it’s the only real option, prices are hugely inflated — our habit is to think of tap water as free,” agrees Triki. “That means there’s a lack of outside investment, and that even water companies are limited in their scope to improve infrastructure, and so the wastage goes on. Water shortage has become a problem everyone knows about but everyone shies away from addressing.”

That’s one reason why Kumulus is conscious of the need to scale up, both in terms of its reach — it’s looking at South Africa, the Greek Islands and California as its next potential markets — and its water production rate. The company sees an advantage in its current machine precisely because it’s mobile and can be installed anywhere, in multiples if required, as it can be powered off the grid via solar panels, or alternatively through another source of electricity.

Speaking of scaling up, Kumulus is now working on a two-year project to develop a shipping container-sized machine it calls the Titan, capable of generating 1,000 liters (or 264 gallons) a day. The company hopes to see them installed on rooftops to supply entire apartment buildings.

These developments mean Kumulus won’t, in the long run, just be going after the bottled water market. Triki wants to target all those places where tap water is potable but of poor quality, too.

“Tap water is our long-term competitor,” he says. “We want to produce water that tastes better, is better for you and is cheaper than tap.” He confidently adds that Kumulus tech could prove to be to water as photovoltaic panels are to energy. In other words, truly groundbreaking.

The Charge will help you move better, think clearer and stay in the game longer. Subscribe to our wellness newsletter today.