There’s a jarring moment towards the end of HBO’s forthcoming documentary Tina (out Saturday) that hits like a ton of bricks when the iconic singer, now 81, looks back and concludes that despite all the happy moments — the fame and success, her loving marriage to husband Erwin Bach — she’s had a pretty bad life.

“It wasn’t a good life,” she tells the camera matter-of-factly. “The good did not balance the bad. I had an abusive life, there’s no other way to tell the story. It’s a reality. It’s the truth. That’s what you’ve got, so you have to accept it. Some people say the life that I lived and the performances that I gave, the appreciation, is blasting with the people. And yeah, I should be proud of that. I am. But when do you stop being proud? I mean, when do you, how do you bow out slowly?”

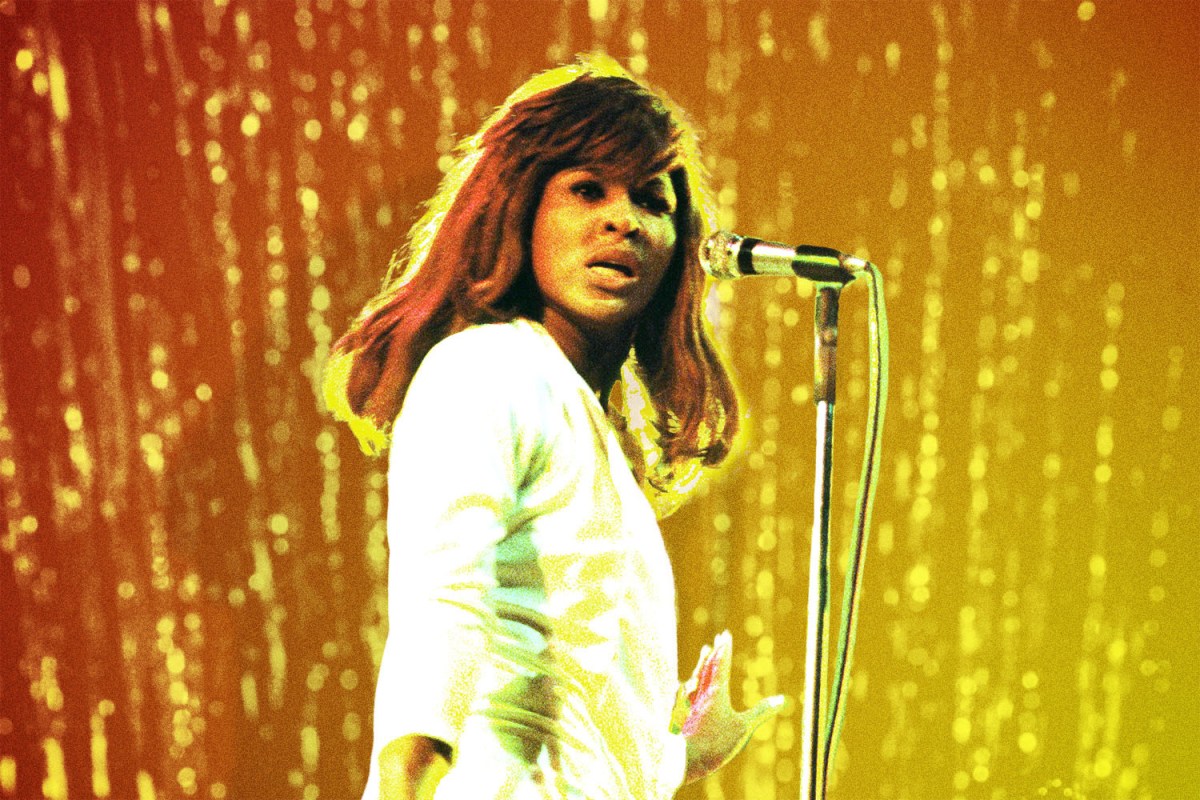

The way she’s decided to do it is telling her story one more time with Tina, intended as a parting gift for her fans before she steps away from public life for good in the wake of recent health problems (including a 2013 stroke, a 2016 bout with cancer, a 2017 kidney replacement and the ongoing PTSD she suffers from as a result of the abuse she endured at the hands of her ex-husband Ike Turner). But despite the harrowing accounts of her time with Ike as well as her childhood trauma (which includes being abandoned by both parents by the time she was 13), Tina is ultimately a story of triumph. It chronicles the way she carved out a comeback as a solo artist in the ’80s — hitting No. 1 and playing to crowds as big as 180,000 as a middle-aged Black woman singing rock music at a time when that sort of thing was unheard of.

We caught up with Tina directors Daniel Lindsay and T.J. Martin, the Oscar-winning pair behind Undefeated and LA 92, about how they brought Turner’s story to life.

One of the things that jumped out to me about the film was the way it addresses the fact that Tina has sort of gotten sick of talking about her past traumas in interviews because it stirs up painful memories and also overshadows a lot of her professional accomplishments. How did you go about toeing that line, where you have to address that stuff, but you do it in a way that’s respectful and not exploitative of her?

T.J. Martin: In early conversations with her, I mean, one big revelation we had was the fact that so much of this trauma from her past was still lurking right around the corner. It was always bubbling underneath the surface. That observation is just something we couldn’t shake, and it felt like it was something that was missing from our collective understanding of Tina and her story. And it felt just very authentic to her experience now, this idea that she hasn’t gotten over the trauma, that it’s a lifelong journey of processing that. So that, essentially, gave us the direction of the film and the POV of the film. Because we were going in head first, it wasn’t really a balancing act. It is a lot of the crux of the film. Right? It’s navigating this world. It’s really like it’s a search to a pursuit of love, but it’s cloaked in trauma. Trauma’s omnipresent throughout the whole thing. But in terms of game plan of not doing the thing to Tina at this chapter in her life that we’re exploring in the film, that a lot of the media did, in terms of rehashing her backstory, bringing her back to that painful place, I think we were really fortunate that we had an amazing archivist in our co-producer, Ben Piner. He was able to, pretty early-on, amass a bunch of archives and specifically the tapes from Kurt Loder. Then, eventually, the tapes from Carl Arrington and the People magazine article. And we were pleasantly surprised by how vulnerable she was on those tapes. That allowed us to, in the time we spent with Tina now, to really get her perspective on things and not force her to have to go through the granular details of some of the more painful times in her life. So the balance ended up being, I think it actually makes for a better film, is to be able to have Tina’s perspective on that, and then jump into that moment in time with something, a piece of archives; it’s a little bit more immediate, and probably closer to what she was feeling at the time, using that archive.

I really enjoyed the way a lot of the shots in the film put us in her shoes, whether it’s the interior of the house or when she talks about remembering flashing lights when she’s crossing the freeway to escape Ike and then we see that montage of flashing lights. What inspired you to tackle those scenes in that way?

Martin: Well, I mean, like I said, those early conversations with Tina, we dictated what the POV of the film was going to be. Then we started to realize, well, there’s really two main characters, and that is Tina and then the narrative of Tina. The top of the film is really giving you the beginnings of these two trajectories, the origin story behind both. But really, from a filmmaking standpoint, it’s the first time we’ve ever really leaned in on dissolves and stuff. Part of that is the film teeters back and forth between the perception of Tina and the internal Tina. And so, once we started creating that film gramarye, where it really was about experiencing the narrative and then using techniques to make sure that we’re actually inside of her head. I love that you point that out because it’s really [something] only so many pick up. People, they might feel that, but it was very intentional to us, at least, to figure out when are we inside of Tina’s head and when are we experiencing Tina’s story externally from the perspective of the media or the public-facing Tina?

Lindsay: As filmmakers, too, we came to make documentaries from the point of view of wanting to make films, and this is just a form that we have found ourselves making films in. We don’t come from a journalistic background. So I think we’re just naturally drawn to this idea. How can we make things as experiential and visceral as possible? It was a real challenge in this film, too, because it is retrospective. In our previous film LA 92, the whole reason we took the approach of just using archive in that was for that exact reason, or one of the reasons that we took that approach. What you’re pointing out was actually a real big challenge for us.

In the process of making this film, was there anything you learned about Tina that really surprised you?

Lindsay: I mean, so much of the film itself, it was new to me because I didn’t know. I’d seen What’s Love Got to Do with It when I was 13 probably. Just down to the fact I had no idea that Ike named her Tina; all of that stuff was news to us. I think the big thing, though, for us, in terms of a discovery, was really after we signed onto the film and knew that we wanted to tell her story, but, also, as T.J. was explaining, think of it as like, “Okay, there’s the story of Tina Turner, and then there’s Tina.” In exploring the story of Tina Turner, we’re like, “Okay, well, what’s the origin of that?” I think, in our minds, we just figured it was when Private Dancer came out, she did I, Tina. And we’re like, “Oh, that must have been where she first talked about what happened to her with Ike.” But then, as we looked at it, we were like, “Oh, it actually comes earlier.” And then we’re like, “Where’s the first time?” And from best we can tell, and from talking to her, that was People magazine in 1981. Really, what was the discovery for us was the date that that happened in 1981 because we knew, at that point, that in that stage in Tina’s life, she was playing the cabaret circuit at hotels and in Vegas and was definitely not in the conscious public eye. So it was a curiosity to us. It’s not like Tina was all over the place and People said, “We got to do a story on Tina.” We’re like, “How did this come to be?” So, by getting in touch with Carl Arrington, and then also talking to Tina and Roger about it, obviously, we learned that was motivated by Tina really wanting to try to separate herself from Ike Turner, especially in the eyes of not only the public but in the record industry. Once we learned that there was just a very clear fascinating irony in that fact that her motivation was to separate herself from Ike and, in many ways, that decision actually connected her to Ike in a way that she was never able to escape.

As you said, she’s told her story many times throughout her career. Why do you think it’s so important for us to revisit it now, at this moment in time? What do you think motivated her to tell it one last time?

Martin: Personally, I think Tina’s story is so rich with courage and acts of heroism that it’s timeless. There’s value. There’s always going to be value in learning and experiencing her narrative. As far as for her, why do this now? That’s probably a question better posed for Tina, but from what we can extrapolate, what she’s saying into the film is very true to her experience now. Which is, she may have retired from the stage, but she very much associates in participation with the rehashing of her story or participating in the musical to give notes on the story and to do interviews and stuff. She’s ready to hang up the story of Tina Turner and really find time to move onto the next chapter of her life without being at the center of attention. So maybe part of, as she says, the end, as Erwin says in the film, the film and this doc and the musical are maybe a closing of that life, and an opportunity to, as she says, bow out slowly. Having said that, it is Tina Turner. I’ve never seen anyone with that kind of energy who spans decades of a career. You never know what’s going to happen next.

Lindsay: In terms of the film being relevant, we were, obviously, conscious of the fact that post-Me Too and Time’s Up that Tina’s story was relevant in there. As filmmakers, we’re never like, “Oh, we’re going to do this because it’s going to say this.” I think it’s more like we enter it with the understanding of the context in which this might come out, but never a design. We never have designs of, “Oh, we’re going to speak to the moment.” You’re just aware of it.

Martin: We talked a lot about, too, Tina is not an activist. She has forged paths because she’s in a search of molding the identity she wants to become. As a result, people are like, “Holy shit.” These are still acts of courage and acts of heroism. But she’s not one to be like, “I did this, and I’m a symbol.” We’ve put that upon her. So that’s why it’s always interesting to talk about her story in the current landscape because Tina’s story does not fit into the narrative of, “I’m doing this. I’m taking the courage on behalf of other survivors.” In her case, she didn’t see any other examples of someone. She was the first. She was doing that as a means to start to carve out her own identity. Ownership is the theme of the film. “I’m doing this because I don’t want to feel owned by this man anymore. And I’m going to take back my name. I’m going to create a solo career, and I want it to look like this.” I think we’ve extrapolated a lot of, rightfully so, a lot of admiration for that. But she doesn’t fit into the narrative of activism and really standing by that platform, and being a voice for others in that regard. She just takes the action.

One thing the film doesn’t address is her son Craig’s tragic suicide in 2018. Was that something she declined to discuss?

Lindsay: No. We did. We talked about it with her a bit. It’s honestly more practical than it seems. It’s very much every chapter of Tina’s life is its own movie, and it spans multiple genres, too, on top of that. So it was really more about sticking to the thesis in the story trajectory that we set out to make that determined what the parameters were of what would be explored. I keep forgetting that she had My Love Story, her second book, which came out right when we were going into production. She was pretty vocal about the love that she experienced, the love story with Erwin that she experienced in the second half of her life, and some of her health issues. We even tried some edits, some versions of the film that incorporated aspects of that. But, for lack of better terms, the film started feeling like a run-on sentence and not through the specificity of looking at Tina’s life and the narrative of Tina through Tina’s lens. And that’s what the film embodies.

On the professional side of things, there’s obviously no way you can cover every career highlight of Tina Turner’s in a two-hour movie. How did you decide which ones fit with the narrative of the film?

Martin: Well, I think we knew right from the beginning, we were never going to make a talking head, real descriptive, breaking down how this song came about. It’s just not what we’re interested in doing. So for us, it was more about just what songs were plot points in the story. So, if you’re telling the story of Tina Turner, you have to address “What’s Love Got to Do with It.” That’s going to come out. So that’s, naturally, a part. “River Deep, Mountain High” is a part of that. “Proud Mary” is a part of it because that catapulted Ike and Tina to a different stage in their career. Everything else was just influenced by the scene, and where we are in the story, and what tone and feeling we were trying to evoke at the time. Tina’s cover of “Help!” was on, I think, the UK release of Private Dancer, not the US one. That’s a known cover that she did, but it wasn’t about, for us, highlighting that. It was just that song, once you understand the pain that she’s lived through, and this search for love, to hear, to have that context in watching her perform that song, suddenly it not only redefines that song, it just also, for us at least, it was such a moving experience. I still can’t watch that without getting moved, getting choked up. It’s just such a powerful performance. So it was much more about what was going to service the film than trying to service the catalog of hits.

What do you ultimately hope people get out of this film?

Lindsay: I think there’s several things. I hope that people are, for those that were aware of Tina before, watching this, are reminded of what an incredible performer she is and what a unique talent she was. And for those that weren’t really familiar with her, I hope that they discover her as a talent. That’s the artistry part of the thing where we don’t overtly talk about that in the film. We wanted to just play her performances in a way where you could just fall into them and be wowed by this presence and this voice. But I think the other thing that I, from the very beginning, when we first talked to Tina and we understood how we wanted to take the film, is this contradiction, or paradox, or whatever you want to call it, about this as a society that the value of survivors coming forward and telling their stories can help shine a light on things and maybe allow other people who have experienced those things to know they’re not alone. So there’s a ton of value in that. But the flip side of that is when we create these symbols out of people, and we ask them to talk about this thing, the positive can also be a negative for them personally, as we show in the film. I think that’s just a paradox that there is no answer to that. There’s no easy thing. I think [my hope is that] people can walk away from the film with a better understanding of that, what it’s like to be the person at the center of something like that.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.