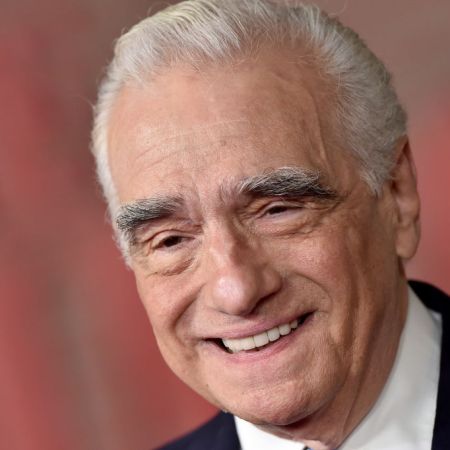

Over 20 years ago, back in 2002, Leonardo DiCaprio received some of the worst reviews of his big-screen career by teaming up with Martin Scorsese. It wasn’t really Scorsese’s fault, or DiCaprio’s; the Titanic star had the misfortune of taking a lengthy absence from movie screens, then returning opposite designated Greatest Actor of Our Time Daniel Day-Lewis, in Gangs of New York, a Scorsese historical epic that was subjected to Weinstein tampering that could not have done its actors any favors. The general consensus was that Day-Lewis more or less acted his young scene partner off the screen, repeatedly and without mercy. He received an Oscar nomination for his trouble. (Catch Me If You Can, which took better advantage of Leo’s boyish guile, course-corrected just a few days later.) But Gangs was also Scorsese’s biggest hit in years, and he would not be dissuaded from re-teaming with DiCaprio, who stuck around for the director’s next three movies in a row: The Aviator, The Departed and Shutter Island, all hits as well. They had one more big success with The Wolf of Wall Street, and then… 10 years passed. Now the pair have reunited for Killers of the Flower Moon, and the longest-ever gap in their working relationship has shifted the nature of that collaboration.

Scorsese arguably helped DiCaprio grow up on screen, though not in the way audiences might have expected back in 2002. Though dinged for a vaguely pipsqueaky quality in Gangs of New York (arguably befitting his scrappy, vengeful character), DiCaprio didn’t try too hard to shake his youthfulness in subsequent Scorsese pictures, even though trying hard in general is sort of his whole deal. (The Academy would later recognize this by awarding him for The Revenant, where he plays a character who is not as memorable as those he played for Scorsese, or Quentin Tarantino, or Baz Luhrmann, or Steven Spielberg, but certainly the one who exerts himself through the most suffering.) Maybe Scorsese wasn’t in any rush to age DiCaprio up, figuring that an energy so different from his longtime collaborator Robert De Niro allowed him to explore a different sort of material: The Aviator trades on DiCaprio’s boy-wonder energy to depict the dashing successes and retreat into exile of Howard Hughes. He’s convincingly tough in The Departed, but with the skittish, wounded quality of a man forced to experience a dizzying array of deceptions and violence. Shutter Island and Wolf of Wall Street make DiCaprio a family man who’s resolutely unprepared for the task at hand, whether in over his head or gleefully embracing debauchery. How old is Jordan Belfort actually supposed to be in Wolf of Wall Street, anyway? It starts with him fresh-faced and bushy-tailed for his first Wall Street job, and ends… sometime later. He’s divorced, with a new wife and some barely-seen kids. DiCaprio no longer has any trouble with adulthood, but he still doesn’t scan as immediately middle-aged.

A decade later, Killers of the Flower Moon is similarly fuzzy, though it seems pretty clear that DiCaprio isn’t supposed to be playing his real-life age of 49. The movie opens with his Ernest Burkhart arriving stateside from service in World War I; the real-life Burkhart was in his late 20s and early 30s during the 1920s, when most of the movie takes place. A war injury leaves him unfit for much physical labor, so his uncle William Vale (Robert De Niro), the white-man “King” (that’s his preferred nickname) of oil-rich Osage country in Oklahoma, takes him under his wing. Vale steers his nephew toward odd jobs like driving around now-wealthy members of the Osage tribe — and arranging murders of various Osage citizens so their money can “flow” back to the white folks.

Everything Martin Scorsese Has Ever Done, Ranked

From the classic films to TV shows, ads and shorts, we rated all things MartyThis plan works especially well, at least for a while, because Ernest is married to Osage heiress Mollie Kyle (Lily Gladstone), putting him (and therefore his uncle) in a position to personally gain from the deaths of Mollie’s family members. Despite this, the movie doesn’t depict Ernest as calculating his way into Mollie’s heart, even if he winds up there because of Vale’s machinations. Scorsese appears to see him as terribly weak, in thrall to his uncle’s authority and convinced, in a twisted-around way, that he’s doing right by his own family by helping to kill off his various in-laws. He’s a bad man, but DiCaprio’s performance doesn’t play like a heel turn; despite the white-supremacist conspiracy, he’s not in Django Unchained mode. It’s here that the friction between DiCaprio’s real age and his on-screen appearance heats up. By all reasonable measures, DiCaprio is too old to play a newish family man who takes orders from his imposing uncle. Yet he’s entirely convincing as a man cowed by his own privilege, someone who’s never needed to develop an actual moral compass, and conspicuously fails to rise to the occasion.

Scorsese has sometimes been criticized for glorifying his amoral characters — and certainly DiCaprio has more screen time in Flower Moon than Gladstone, who is wonderful but necessarily sidelined for stretches of the film as her husband also helps poison her via diabetes treatment, to keep her from learning too much, too soon (Scorsese cuts back to her strategically, so that she’s never far out of mind even when she’s offscreen). Whether or not audiences registered the moral voids at the center of movies like Goodfellas or Wolf of Wall Street, there’s no Jordan Belfort swagger to Ernest. Even when he repeatedly expresses his love of money, he doesn’t share Beflort’s obvious glee in either pursuit (or, more accurate to Belfort’s case, instant-gratification consummation). If Belfort’s appetites for women and lucre were base, Ernest’s feel positively unformed, a kind of default setting. He has more in common with the chillingly shruggy murderer De Niro played in The Irishman, Scorsese’s previous 200-minute American epic.

As in that movie, Scorsese finds dark humor in the quotidian details of very bad acts; this, more than letting the audience in on vicarious thrills, are how he humanizes his later-period criminal characters. In retrospect, The Wolf of Wall Street, the previous DiCaprio/Scorsese joint, feels like a blowout farewell party for Scorsese’s use of movie stars to draw us into various criminal worlds. He still casts big names — he worked with Al Pacino for the first time on The Irishman, and several household names pop in for the last 40 minutes of Flower Moon — but increasingly, his characters get swallowed up by history by the end of the story. That’s there in the endings of movies like Raging Bull and Goodfellas, of course, but those movies zoom in on their wrecked protagonists, while The Irishman and Flower Moon both find ways of pulling back. Flower Moon has a particularly audacious finale that I won’t spoil, except to say that it doesn’t feature any of the actors from the preceding 200 minutes: Not DiCaprio, playing the hero of his own story who’s too thick to realize he hasn’t done anything heroic, and not Gladstone, playing something closer to an actual hero.

I suppose this particular switch-up could be read as a form of directorial ego — Scorsese emphasizing that his actors are, essentially, pawns in a larger story he’s telling, which itself has the limitations of fiction, even if it sprawls out toward the three-and-a-half-hour mark. But the movie’s final scene took my breath away, specifically because the way it denies the audience a traditional actor-led catharsis. It’s particularly bold to do this with DiCaprio on hand. He no longer inspires the same teen-girl mania he did in Titanic (another historic tragedy, albeit one with the courtesy to play out openly and obvious), but he’s arguably as famous as ever, now an Oscar-winner who hasn’t a box office flop in a decade and a half. To his credit, he’s never let that get in the way of whatever unflattering business that Scorsese cooks up for him; he seems, even, to embrace it. In an earlier iteration of Flower Moon, he was set to play Tom White, the agent of the nascent FBI who helps crack the Osage murder case, until he pushed to play Ernest instead (Jesse Plemons fills the FBI agent role). Scorsese has so altered the trajectory of DiCaprio’s career that Tom White doesn’t seem like a particularly obvious part for Leo, even if it was presumably a larger one in earlier drafts. DiCaprio’s take on American masculinity is sweatier and less steady, with unearned self-confidence until it gives way to self-doubt, and presenting as older or wiser won’t help matters. Back in Gangs of New York, he was derided for lacking the stuff of a two-fisted underdog hero. Nearly 20 years later, it seems increasingly likely that this was the point.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.