If you want to ensure your voice is heard, you could do worse than becoming the president of the United States. Americans, like the rest of the world, have no choice but to pay heed to the commander in chief. (Even if they aren’t crazy about the things being said or the person saying them.)

It hasn’t always been this way. Technology has changed how the word is spread. There’s also been a revolution in the manner U.S. presidents decide what they should (or should not) share, which invariably evolves a little more with each election.

This is how presidential communication got where it is today.

1789: The George Washington Way. The Father of Our Country is an utterly unique figure in presidential history: The job wanted him more than he wanted it. The Electoral College twice chose Washington unanimously and he stepped away rather than serve a third term. Freed from having to pursue the job, George could take an impressively philosophical look at the position. He agonized over how to “maintain the dignity” of the office while still interacting with the American public in a letter to John Adams, even wondering if there might be “any impropriety” in his casually visiting friends. (Does the president get to just pop in on people?) Washington also worried about endless political conflicts, writing to Thomas Jefferson that he was “no party man myself.” The result was a dignified, nonpartisan tone his successors would struggle to match. Yet though they invariably fell short of Washington’s standards, they still benefited from…

The Persuasion of the Presidency. George Washington immediately stamped the office with immense prestige. Even as some of his successors did all they could to sully the position—looking at you, Andrew Johnson—that status has never gone away. Indeed, the president’s words can be borderline brainwashing. This is not a figure of speech. Marc Savard has been hypnotizing audiences in Vegas for over a decade, winning two “Best of Las Vegas” Awards. (He even hypnotized his wife so she could give birth to their four children without anesthesia.)

Savard explained to RCL how being told something by a person in a “position of power” can literally alter the subconscious mind. He cited two examples. One is a doctor informing a patient they have six months to live. In many cases, the patient holds the physician in such high esteem that simply hearing this can shorten their life.

The other: “The President of the United States can say, ‘Hey, there’s a shortage of water. You’re gonna run out of water!’ 300 million people will run to the store and buy water.” There may be a perfectly valid reason for this announcement. But there might not be and millions will still respond immediately. Like a doctor, the president’s words are often accepted without question. (And presidential utterances are far more influential because even the most successful physician doesn’t have 300 million patients.)

George Washington grappled with the implications of the statements he made in office. It’s a struggle each president still faces today. (And if they’re not consciously addressing it, their critics surely will.)

1801: A Silent State of the Union. Washington could be decidedly reserved, but at least he was willing to talk. Thomas Jefferson observed that while the Constitution required the president “from time to time give to the Congress information of the state of the union,” it did not specify it needed to be spoken. Accordingly, Jefferson chose to write it up but not actually say it. He even sent a letter explaining his reasons for not doing so. Among them: It was “inconvenient.” (On a deeper level, he explained Congress should take time to contemplate the message, rather than risking the State of the Union functioning as little more than the pep rally it often is today.) Unspoken State of the Unions became accepted practice until Woodrow Wilson resumed the talking in 1913.

1840: Hit the Trail. George Washington prided himself on avoiding even a hint of campaigning. Future presidential candidates were thus forced to appear almost disinterested in the job, all the while having their surrogates rip their opponent to pieces. (By 1800, Adams’ campaign accused Jefferson of being a “mean-spirited, low-lived fellow, the son of a half-breed Indian squaw, sired by a Virginia mulatto father” while Jefferson’s team offered that Adams was a “hideous hermaphroditical character, which has neither the force and firmness of a man, nor the gentleness and sensibility of a woman.”) William Henry Harrison took a step out of Washington’s shadow by publicly campaigning for the job—actually going out and giving speeches on his own behalf. The universe seemed to frown on this behavior. While Old Tippecanoe won the election, he gave an epic inaugural address lasting a punishing hour and 45 minutes, caught a cold and died just 32 days into his term.

1861: Lincoln on the Line. Abraham Lincoln was born too soon for the telephone, but made great use of the telegraph. Initially cautious with this technology—roughly one telegram sent a month—in 1862 he began sending dozens per week as he strategized with his generals during the Civil War. He also received telegrams to help him determine if leaders were accurately reporting their experiences back to him. (This led him to mock General McClellan for not pursuing Confederate forces while claiming his horses were tired: “Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigue anything?”) It was a hint of the world to come, with the president still in Washington but connected to the rest of the country (and, eventually, the planet).

1896: The Ultimate Porch Campaign. Incredibly, as the 20th century drew near, it was still possible to run a winning presidential campaign with a candidate who literally would not leave his house. Rather ingeniously, William McKinley had the people come to him. (Railroads and improved transportation let him draw 750,000 to his Canton, Ohio home.) While McKinley chose not to travel for deeply humane reasons—he refused to leave the side of his sick wife—it was also political calculation at its finest. (Their “home” was a residence the McKinleys hadn’t live at for more than two decades which they rented to show their deep roots in the community.)

1919: Taking It to the People (Directly). Woodrow Wilson had already resumed the spoken State of the Union in 1913. So when it came time to win ratification for the League of Nations, he decided to speak to the American people in person. He would travel 8,000 miles in just 22 days. It didn’t work, as the League failed to pass and the Republicans took back the White House in 1920. Beyond this, the journey nearly killed Wilson, triggering a stroke that incapacitated him. Presidents to come would share Wilson’s desire to take their message straight to the people. They would be fortunate enough to get the technology to make that dream more and more possible.

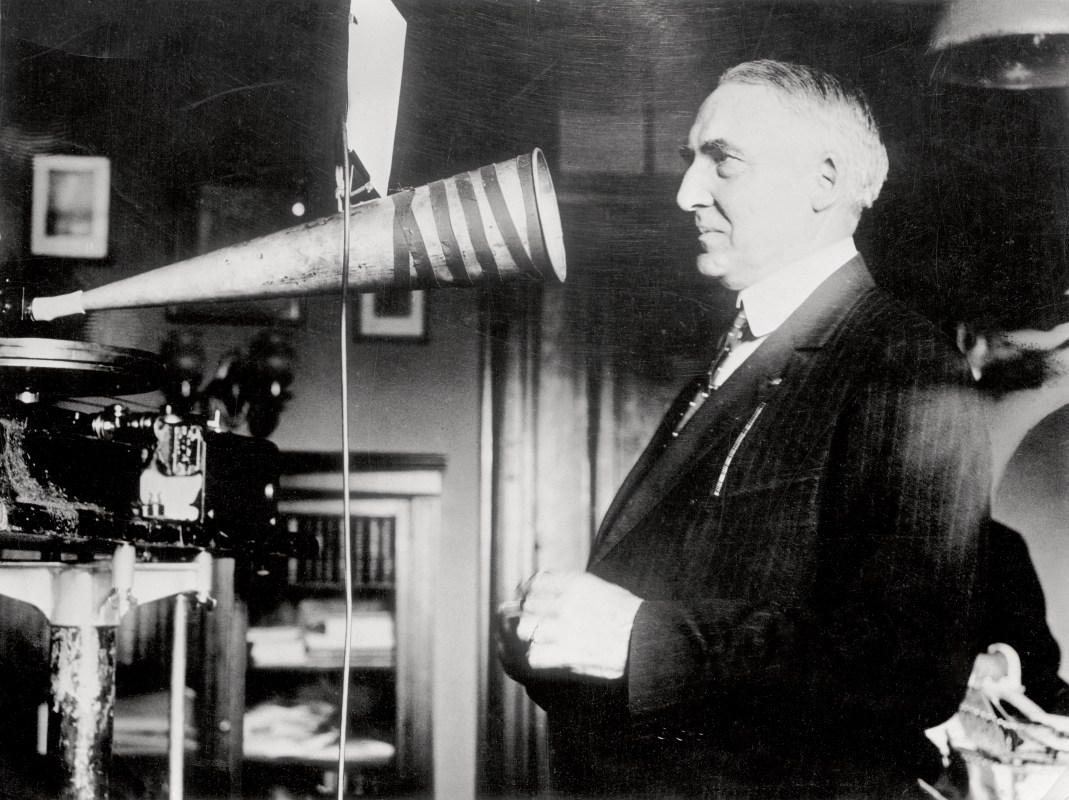

1922: Taking It to the People (Virtually). On June 14, Warren G. Harding became the first president to be heard on the radio. He was recorded addressing a crowd at the dedication of a memorial site for Francis Scott Key. It would take another three years before Calvin Coolidge became the first president to give a talk specifically designed for the radio. And it would be another eight after that before a president finally recognized this medium’s full potential.

1933: Just Chatting. “The president wants to come into your home and sit at your fireside for a little fireside chat,” declared announcer Robert Trout in a radio broadcast eight days after Franklin Delano Roosevelt took office. This was the first Fireside Chat, a series of talks that could last up to 45 minutes. They proved an invaluable resource for FDR as America struggled with the Great Depression and World War II during his three full terms in office. (He died early in his fourth.) Radio allowed him to connect directly with Americans across the nation in a way no previous president had. Effective as this tactic was, FDR was careful not to overuse it. He gave only 30 of them over 12+ years in office—less than three annually. Here’s one of his most famous:

1955: Showtime. Dwight Eisenhower became the first president to allow TV cameras in the White House. Press conferences—and general coverage of politics in general—would never be the same, as voters across the country could see what was happening with their own eyes. (Or at least witness what the president and his handlers were comfortable with them seeing.)

1961: Live. John F. Kennedy one-upped his predecessor by agreeing to have a press conference that was broadcast live, including a question and answer session with reporters. As the video below shows, from now on a candidate who looked good on camera would have a distinct edge over the Nixons of the world.

1981: So Long, Silence. Jimmy Carter provided only a written State of the Union and not a spoken one, the last time that has happened to date. He did so as a lame duck who’d lost his reelection bid to the former actor Ronald Reagan, a reminder that being able to command the camera was only growing in importance.

1992: Bill Blows. Once there were unofficial but extremely strict restrictions on how a presidential candidate could campaign. By the time Bill Clinton was playing sax on The Arsenio Hall Show, clearly any lingering limits were being swept away. (Clinton shattered another in 1994 when he answered a teenager’s question at an MTV forum and confirmed he usually wore briefs, not boxers.)

2010: The Debut Tweet. Barack Obama unleashed the first presidential tweet: “President Obama and the first lady are here visiting our disaster operation center right now.” While Obama pushed the button to send it, the actual message was composed by the American Red Cross to promote relief for Haiti. His successor would take complete control of the medium.

2017: Make It Personal. Donald Trump decided to keep using his own Twitter handle as president: “If I do a news conference, that’s a lot of work. I can go bing bing bing and I just keep going.” He uses technology to communicate directly with voters, much as FDR did with the Fireside Chats.

Of course, there are differences. FDR was extremely sparing with his use of Fireside Chats, averaging only a few annually. Trump sent out over 2,500 tweets his first year in office—roughly eight per day. At times they flirted with being unethical or possibly even illegal, as when he hinted in advance at the carefully guarded job report numbers. At times they were simply wrong, as when he retweeted fake videos of assaults by a “Muslim migrant.” And thanks in large part to Trump’s frequent misspellings, at times they’ve been utterly baffling. (He has coined the terms “unpresidented” and “covfefe.”)

Quite simply, this is the first time we’ve had the technology to let a person share their thoughts with the world in something approximating real time and a person in the presidency who’s inclined to do just that. (Witness Trump’s ongoing public feud with his SNL impersonator Alec Baldwin.) Yet it also has major constitutional significance. The U.S. Justice Department is in the midst of a legal battle over whether the Constitution lets him block Twitter users.

George Washington mused to Adams if the president should be “equally distant from an association with all kinds of company on the one hand and from a total seclusion from Society on the other.” Would he approve of the U.S. president using Twitter, particularly when matters of state, campaign materials and personal musings flow from the same source? Only one thing is certain: George could never have imagined the Leader of the Free World would get over 50 million followers on Twitter—10 times the entire population of the U.S. when Washington died in 1799— yet it still wouldn’t be half the total amassed by Katy Perry and Justin Bieber.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.