It gets them every time.

“How many of you,” I ask a roomful of half-awake 18-year-old students, “are familiar with the term MILF?” There’s a frenzied exchange of knowing smirks.

Determined to maintain an academic tone, I ask the next question. “And how many of you know the etymology of this acronym?”

“Mom I’d like to fuck!” one particularly enthusiastic scholar blurts out.

“Thank you,” I say over the tsunami of snickers. “That’s what it stands for. But where does it come from?”

Roughly half the students in my film elective correctly identify Stifler’s mom, the sultry divorcée from the 1999 comedy American Pie, as MILF Zero, the woman to whom those four letters owe their provenance. “Here’s the thing,” I press on, “Stifler’s mom may be Hollywood’s most explicitly sexualized and predatory mother. But she wouldn’t exist without Mrs. Robinson.”

“Who’s Mrs. Robinson?” a student inevitably asks. And that’s where our unit on The Graduate begins.

***

The Graduate, in case you need a refresher, is Mike Nichols’s iconic 1967 film centering on Benjamin Braddock, a young man played by a splendidly awkward Dustin Hoffman. Benjamin returns to his affluent California family after a successful conquest of some unnamed eastern college feeling lost in life despite countless achievements. Enter Mrs. Robinson, the wife of Mr. Braddock’s law partner. Mrs. Robinson, brought to life by the vivacious Anne Bancroft, proceeds to help Benjamin become a man.

In American popular culture, Mrs. Robinson is the O.G. hot mom, matriarch of a cinematic family tree that abounds in forbidden fruit. Her descendants include Maude (Harold and Maude, 1971), Marion Wormer (Animal House, 1978), Stella Payne (How Stella Got Her Groove Back, 1998), Kathleen “Kitty Cat” Cleary (Wedding Crashers, 2005) and, of course, Stifler’s mom. Although earlier films flirted with the taboo notion of an older woman taking a younger lover, The Graduate was the first to confront the subject head on. That it did so with an unapologetic celebration of female sexuality, compounded by its subversive portrayal of generational strife, is what made its release so socially controversial, critically successful and outrageously lucrative. The film grossed $105 million in 1967 and received seven Oscar nominations, winning one, for Best Director. As often as the Academy flubs this particular award, they got it right with Nichols. If nothing else, The Graduate is a revolutionary piece of filmmaking.

The film’s narrative and technical elements transformed the topography of American cinema by changing the rules for what stories could be told en masse and how directors could tell them. While Nichols isn’t working from original source material — The Graduate is based on a 1963 novel of the same title by Charles Webb, who famously sold the film rights for a flat fee of $10,000 rather than opting for a slice of the profits — he is responsible for turning the novel’s antagonist into a prowling and rapacious maneater. A dialogue-heavy work, Webb’s version includes few cues as to Mrs. Robinson’s appearance beyond a brief snippet when she first appears in the story: “Mrs. Robinson was wearing a shiny green dress cut very low across her chest, and over one of her breasts was a large gold pin.” That’s all we get. Her sexuality is discernible, but its valence is unclear.

Using the tools of his medium, Nichols is much more decisive. Consider this shot early in the film, when Mrs. Robinson has just persuaded Benjamin to leave his own graduation party and drive her home:

A master of composition, Nichols has a clear vision for how he wants his audience to perceive this femme fatale. The tiger-striped dress, the brilliant green vegetation that looks more like a jungle than a backyard, the actress perched high above the camera — Mrs. Robinson is a predator. And she’s on the hunt.

In the next shot, arguably the film’s most iconic, Nichols guides our attention to her prey with a slightly more overt arrangement:

An incredulous Benjamin has just uttered, “Mrs. Robinson, you’re trying to seduce me.” The most striking element of this shot is the framing. Nestled under Mrs. Robinson’s leg and flanked by her flora, Benjamin is trapped. Nichols also lights the shot to emphasize the scene’s sexual politics. Benjamin, innocent and chaste, is bathed in light. Looming large in the foreground, however, is that leg: dark, mysterious, enticing.

***

We have a word for predators like the one embodied by Mrs. Robinson: cougar. The designation is similar but not identical to the one that would pop up three decades later — MILF — in a bawdy teen comedy.

Why does the distinction even matter? Thanks to American Pie, we can retroactively call Mrs. Robinson a MILF. This word says a lot — about the person it refers to, sure, but also the culture that invented it. But what about “cougar”? Like most pop vernacular, it is difficult to pinpoint the moment when the term entered our cultural lexicon.

The term, which refers to an older woman who consorts with younger men, is fresher than you might guess. Most accounts, including a 2008 article in the Chicago Tribune, locate early usage in Canada. One unsubstantiated rumor claims that the 1989 Vancouver Canucks referred to their elder groupies as “cougars.” Another points to the Canadian website CougarDate.com, which launched in 1999. But it’s Valerie Gibson’s 2002 nonfiction book Cougar: A Guide for Older Women to Dating Younger Men that is most widely credited with originating the species.

Gibson, a former sex columnist for the Toronto Sun, says she first heard the term in Canadian bars in the early aughts, and decided to embrace it wholeheartedly. The book begins shortly after her fourth marriage has ended.

“I found that being forty-four, single, and hotter than a chili pepper was by no means the social drawback one might expect,” she writes. “In fact, far from finding myself alone and dateless, I appeared to be just what quite a number of men — younger men — were after. They certainly turned out to be what I was after.”

When contemplating the cultural legacy of The Graduate, the murky etymology of “cougar” is telling. The fact that the term itself is relatively new highlights the prescience of Nichols’s vision; Mrs. Robinson was a cougar before cougars existed, at least linguistically. As is often the case, the idea is much older than the word. Nichols, though, did not invent a new type of female character. What he did was much more destabilizing: he trained a spotlight on an archetype that had been relegated to the shadows of humanity’s collective consciousness for millenia.

***

Archetypes — heroes, villains, Chads, Karens — exist for a reason. They establish the borders and expectations of human experience by conceptualizing the different roles individuals can occupy in art, as well as life. And as is the case with most archetypes, the natural starting point for a discussion on the legacy of the cougar is ancient mythology, which brings us to Joseph Campbell.

In his 1949 masterpiece, The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Campbell argues that all mythological narratives, regardless of their cultural origin, share the same fundamental structure. Campbell outlines this structure in his introduction: “A hero ventures forth from the world of common day into a region of supernatural wonder: fabulous forces are there encountered and a decisive victory is won: the hero comes back from his mysterious adventure with the power to bestow boons on his fellow man.” Replace “hero” with a proper noun — Frodo Baggins, Luke Skywalker, Harry Potter, Katniss Everdeen, Jake Sully, Maria von Trapp — and you begin to see how that sentence serves as a blueprint for every story ever told.

Shortly before his death in 1987, Campbell was interviewed by Bill Moyers, the acclaimed journalist and Johnson administration Press Secretary. Moyers intuited a gender imbalance in Campbell’s approach, and asked the scholar if only men could be heroes. Campbell quickly refuted the idea:

“Oh, no. The male usually has the more conspicuous role, just because of the conditions of life. He is out there in the world, and the woman is in the home … Giving birth is definitely a heroic deed, in that it is the giving over of oneself to the life of another.”

Beyond its resemblance to a 1950s bumper sticker, that last sentence is noteworthy for highlighting the structural limitations imposed on female archetypes. Most ancient and early modern constructions of femininity defined women in terms of their relationship to men, hence the Madonna/Whore dichotomy, an archetypal view of womanhood that predates the Bible. In this model, a woman can be one of two things: a nurturing mother or a deplorable slut. In her 1991 essay “Archetypes, Stereotypes, and the Female Hero,” classicist Terri Frontgia identifies the underlying problem with Campbell’s praise for motherhood. While acknowledging the heroism of motherhood is affirming, Frontgia says, it also works to keep female identity in a tightly confined box and is “yet another manifestation of women’s old nemesis, biological determinism.”

Because this view is pervasive in mythology, it is almost impossible to find examples of women who operate outside the paradigm — almost. Thankfully the ancient Greeks had a useful literary device that allowed them to explore taboo aspects of human nature without attributing them to humans: the deities.

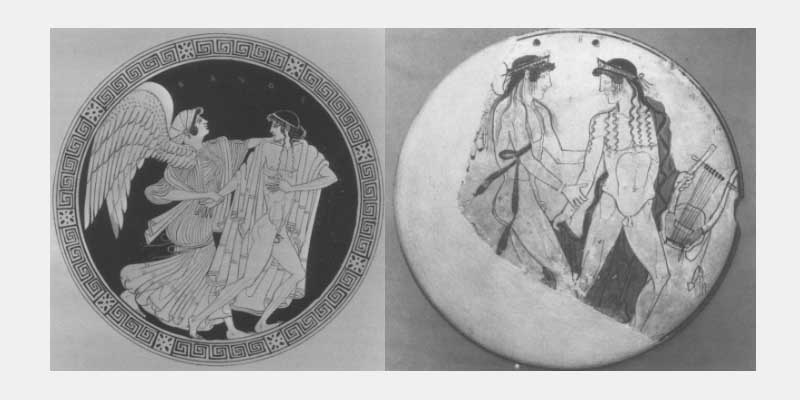

The Greek goddess Eos, the personification of dawn, is one of the earliest incarnations of the archetypal cougar. She was known for kidnapping young men and leading them into the woods for sexual encounters, her abductions so renowned that depictions of them adorned many Grecian vases, such as the one below (left), believed to be from the 4th or 5th century BC:

Note the strength of the winged Eos’ grip on the boy, Tithonos: she has him by the wrist and neck, as if wrestling a calf to the ground. And should there be any doubt about who holds the power here, their dress provides further clarity. Eos is elegantly festooned in robes and scarves; Tithonos is completely starkers.

Likewise, there are plenty of depictions in which male gods abduct mortals (both women and young men), like Zephyros does in the vase on the right. But these scenes tend to paint a different picture: the male gods never appear to take their mortal prey by force, instead winning affection via a seductive glance or a gentle caress of the arm.

Eos, meanwhile, refrains from making eye contact with her mortal. The irony here is comical — the male deity, paragon of strength, resorts to sensuality, while the female deity relies on brute strength — but the implications are much darker.

“It has been suggested,” Wellesley classicist Mary Lefkowitz writes, “that painters of these vases concentrate on the negative aspects of the abduction in order to send a covert message about women’s sexuality.” The message, to finish Lefkowitz’s thought, could be that unbridled female sexuality spells danger for males. To project this fear onto a grander canvas: female agency, as embodied by a woman who cannot be defined or explained by the Madonna/Whore model, poses a significant threat to patriarchy. This conceit may sound extreme, but it explains why nearly 1,000 years would pass before a mortal female character explicitly fulfilled the cougar archetype.

Entrenched in the heart of English patriarchy as a courtier to King Edward III, Geoffrey Chaucer was an unlikely candidate to craft the voice of one of the loudest cougars in the history of literature.

The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer’s 14th-century opus is essentially a road-trip narrative. A group of pilgrims travel together from London to Canterbury and engage in a storytelling competition to pass the time. These pilgrims come from all walks of life — the pilgrimage itself, to a storied cathedral, appears to be their only unifying trait — and Chaucer uses the occasion to satirize various elements of medieval society.

Although the pilgrims are predominantly male, the Wife of Bath is easily Chaucer’s most memorable character. (She’s also had the greatest influence on contemporary pop culture: the Mel Gibson rom-com-fantasy flick What Women Want and a quietly awesome Les Blank documentary called Gap-Toothed Women are both inspired by her.) What makes her so striking is the way she flaunts ideas that art and humanity sought to repress for millennia. Similar to Valerie Gibson, the Wife has been married several times. This is how she talks about her fifth husband — as translated from the original Middle English courtesy of Harvard:

He was, I believe, twenty years old,

And I was forty, if I shall tell the truth,

But yet I had a colt’s tooth.

With teeth set wide apart I was, and that became me well.

And a few lines later:

And, truly, as my husbands told me,

I had the best pudendum that might be…

For God as my salvation,

I never loved in moderation.

The number of parallels one can draw between the Wife and Mrs. Robinson is striking: an older woman with a ravenous sexual appetite takes a younger lover without a modicum of shame. In many ways, the Wife would have been far more unsettling to her contemporary world than Mrs. Robinson was to her own. Note how she repeatedly references her “pudendum” (translated from “queynte,” an early iteration of the C-word). Such language might have been tolerated from the mouth of a brothel wench, but the Wife is nobility; imagine Caroline Kennedy dishing to a room full of strangers about her lady parts. As arresting as the Wife’s language and sexuality are, however, they would not disturb Chaucer’s audience nearly as much as the substance of her message.

A self-proclaimed expert in “the woe that is marriage,” the Wife promises to tell her fellow pilgrims a tale that will answer the question that has eluded every husband since Adam: What do women truly want? And she does. To make a long story short, the Wife claims that every woman’s greatest desire is sovereignty: control over her own life as well as her husband’s.

In a 1976 essay, Chaucerian scholar Kenneth Oberempt considers how medieval society would have reacted to such a brazen claim. The Wife of Bath would be viewed as “an unmitigated advocate of vaginal politics and her argument for wifely sovereignty [as] evidence indeed of her perverted character,” he writes. This psychology goes a long way in explaining why prominent female characters who approach today’s conception of the cougar are an endangered species in the Western canon.

To her credit, the Wife practices what she preaches. As she proudly tells the pilgrims when reflecting on the power dynamics in each of her five marriages: “I had them wholly in my hand.” This language should resonate with contemporary readers. As any Seinfeld fan knows, “hand” is a universal symbol for power and control.

***

There is one shot in The Graduate that makes my students blanch every time I screen the film. It occurs near the halfway point. Elaine, Mrs. Robinson’s daughter and Benjamin’s ultimate love interest, has just discovered the truth about the relationship between Benjamin and her mother. As Benjamin leaves the Robinson’s house, he exchanges one last glance with his ex-lover:

“Tell me what you see,” I prompt my students when we revisit this shot. Their visual literacy skills have come a long way since the course began.

They see everything: the wide, slightly down-angled shot Nichols uses to pin Mrs. Robinson in the corner and make her look weak (for the first time in the film); Benjamin looming large in the foreground (occupying more space than Mrs. Robinson for the first time in the film); the black-and-white contrast that connotes prison; and, of course, the fact that Mrs. Robinson’s right hand is gone. The implication is glaring: Mrs. Robinson has lost the power she once wielded so fiercely.

This symbolic amputation — castration through a Freudian lens — represents the demise of a devious character. For cougar sympathizers, the message is disheartening. As progressive as The Graduate is for bringing a controversial archetype into the mainstream, the film ultimately retreats to a patriarchal safe space by turning Mrs. Robinson into a pitiful villain. Why, some viewers might ask, can’t the cougar win the day? The simplest answer, and it’s an unsatisfying one, is that it was 1967. Thankfully, we’ve come a long way.

Jeanine Stifler does not appear in the flesh until the final 14 minutes of American Pie. Paul Finch, a drooping and dejected high-school senior who recently squandered his chances of losing his virginity due to a “bathroom incident” incited by one Steven Stifler, stumbles into a room that has been cordoned off from the younger Stifler’s prom afterparty. Who does he encounter? Stifler’s mom, of course. They engage in flirtatious repartee and the overtones of The Graduate are not subtle, namely because Simon and Garfunkel’s “Mrs. Robinson” is simmering in the background.

When Finch asks Stifler’s mom if she would object to him calling her “quite striking,” she gives a demure smile and asks, “Mr. Finch, are you trying to seduce me?” In a role reversal of the adjacent scene in The Graduate, it feels like the young, untested cub has the upper hand. For a moment, it feels like the film has no intention of advancing the notion that the cougar poses an existential threat to the male race. But then the camera pans to Stifler’s mom as she casts her gaze on the pool table. When she turns back to Finch, his expression tells us he’s scared shitless.

Stifler’s mom puts down her Scotch, grabs Finch by the wrist, and purrs, “You’re dead.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.