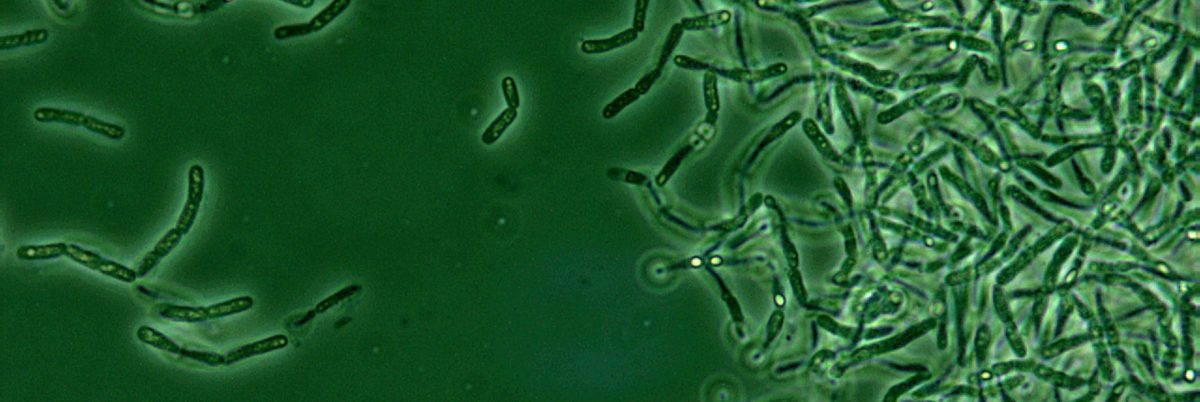

The Department of Defense made a stunning admission in the summer of 2015: because of faulty testing, it had accidentally shipped live samples of bacteria that causes anthrax to dozens of facilities in the U.S. and around the world over the course of more than a decade.

The samples were supposed to be inactive, to be used in the development of testing and detection equipment, and for the treatment for anthrax outbreaks.

The government says that because the anthrax bacteria “is both infectious and exceptionally resilient, it is ideally suited for potential adversaries’ biological weapons programs,” which is why the Department of Defense needed a “strong countermeasures program.”

But the samples the department had shipped to labs in each U.S. state and as far away as Japan contained live spores, and now the very program meant to counter an outbreak was in danger of starting its own.

“By any measure, this was a massive institutional failure with a potentially dangerous biotoxin,” then-Defense Deputy Secretary Bob Work told reporters.

Incredibly, however, an Army review found that no one was sickened by the live bacteria over the 12-year mistake and a threat to public health never emerged. After realizing the emergency, all the batches were quickly accounted for or destroyed, the Defense Department said.

At the time the military promised to shape up when it comes to bio-safety, but a new government report says that in trying to fill the safety gaps, some military scientists have found themselves plagued by a different threat —bureaucracy.

“Staff is not getting clear guidance and said it was ‘death by red tape’ and that they were ‘more afraid of the paperwork than the pathogens,” reads a sample comment in the new Government Accountability Office (GAO) report. Another says, “There is an unwillingness to accept risk. Zero percent risk is not possible when working with biological select agents and toxins (BSAT). The only way to get 0 percent risk when working in a laboratory is not to do any work.”

The report was the result of GAO investigators checking in on the military’s progress on the 35 changes it planned to implement in the wake of the 2015 fiasco. The report found that three years later, the military had completed 18 of the changes, but was still working on the 17 others.

“DOD [Department of Defense] has taken steps to improve biosafety and biosecurity and made significant progress in addressing the recommendations from the Army’s investigation report,” the GAO said. “The department currently has an opportunity to take several additional management actions that, if implemented fully, will help it capitalize on the progress that it has made.”

But while GAO was supportive of the military’s corrective actions, the scientists themselves indicated the strategy had gone overboard.

One lab employee complained that they can no longer ship inactive agents through FedEx, as they apparently used to do. Now it has to go through military transport which makes the process “very expensive and much more complicated.”

“We can no longer use FedEx to ship inactivated material. But it’s ridiculous because the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention can call something a clinical sample and get around this,” an unidentified lab staffer complained.

Another said that at least one of the safety measures had the opposite of its intended effect. The military temporarily revoked the use of inactive agents, but that just meant that a lab did some testing with live agents instead, “which is actually more dangerous,” the staffer said.

Overall, another said they feared the slowdown in the work was going to cause an operational gap.

“We are losing capability, in general, while a private competitor is trying to obtain capability,” the staffer said.

The scientists and lab staffers who spoke to the GAO weren’t all critical, however. New procedures have increased communication, transparency and cooperation between labs, the report says.

And, of course, new safety procedures have to date prevented another accident like the one revealed in 2015.

The GAO said it made recommendations for the Defense Department to better evaluate the effectiveness of the changes they’re making, recommendations with which the military concurred.

“[W]e obviously as a department have a lot of work to do,” Work told reporters in 2015. “I mean, we have a lot of work cut out for us. The American public expects more from the Department of Defense, and we expect much more of ourselves also. [Then-]Secretary [of Defense Ash] Carter has made plain to me and all the senior leadership of the department that he expects these issues to be dealt with swiftly and comprehensively to ensure that a failure of this sort never happens again.”

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.