What makes for a compelling image? For artist Johanna Stickland, the answer to that question varies. Some of her photographic work draws on portraiture to capture an elusive quality in the subjects, while other images turn the human body into something intriguing yet unfamiliar — what she refers to as “tender, intimate photos.” She’s also pushed at the form of what photography can do, adding paint to images to heighten certain qualities and pursue an elevated sense of emotion.

Stickland’s interest in photography began at a young age, when she was on the opposite side of the camera. Her work has appeared in places like Juxapoz and Numero Magazine, as well as in the well-received 2018 group show The Female Lens: 9 Contemporary Female Photographers at London’s Huxley-Parlour Gallery.

Her forthcoming show of photographs, PRISM, opens on July 20 at Brooklyn’s Thames Art Center. The show — and an accompanying book — serve as an overview of her work to date, zeroing in on the themes and motifs that Stickland finds most compelling. InsideHook chatted with Stickland about her art, her preferred materials and the making of PRISM.

*This interview has been edited for length and context.

InsideHook: What initially drew you to photography as a medium? And as a photographer, what are your preferred themes?

Johanna Stickland: I started taking photos about 13 years ago. When I was 14, I was a fashion model; I was used to being the subject. I didn’t really enjoy modeling, but I enjoyed working with photographers and the special relationship between the subject and the photographer. I quit modeling and I just decided to turn the camera on myself and take self-portraits, take photos of my friends, my mom. It started very naturally; I always felt drawn to photography.

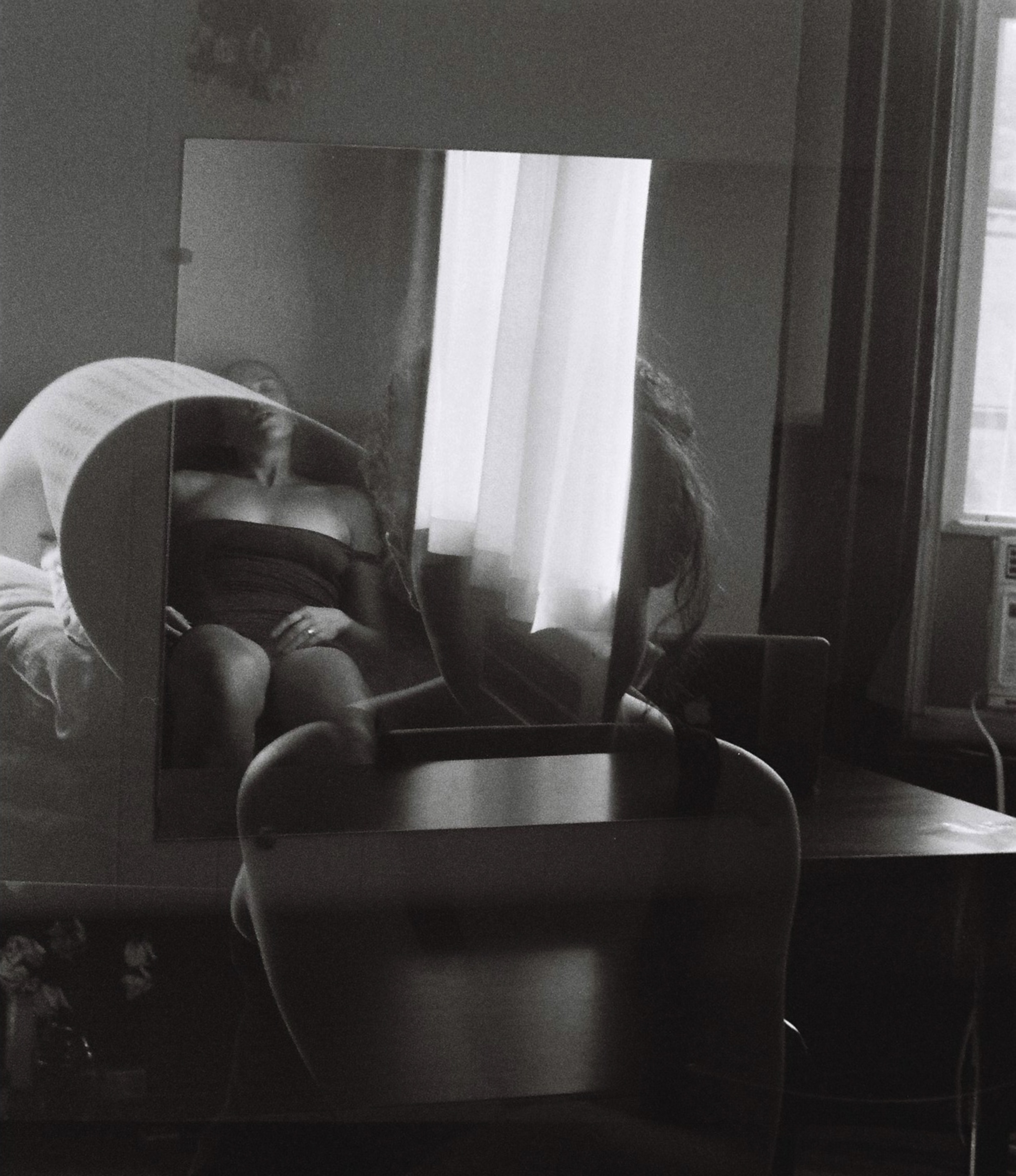

The things that I focus on are women, intimate snapshots of life, body parts — tender, intimate photos.

In terms of the relationship between the photographer and the subject, how did being on one side of that inform your practice now, when you’re taking a photograph of somebody else and not yourself?

Because I had experience as a subject, I’m really sensitive to how other people feel — making sure they’re comfortable, making sure it’s enjoyable, and that the comfort is there, the trust is there. I think it’s really about trust, and it’s a sacred thing. When you’re photographing someone, you’re taking their soul in a way. So I don’t like photographing people that don’t like to be photographed; that’s why I could never do street photography. There’s an intimacy that I think is very sacred.

Is there a specific challenge as far as creating that level of intimacy or that level of privacy, when you’re working with someone who you haven’t worked with in that context before?

Yeah, that can be challenging. Usually people know my photos and they enjoy the style, the softness, the tenderness. My mom, for example, is an actress, so she loves having her photo taken.

In terms of that softness — do you have a specific way that you achieve a certain look or a certain feel? Is it more of just an emotional thing or is it more technical, working with certain lighting, certain equipment, certain spaces, that kind of thing?

I’ve never really had a set camera that I use or lights or anything. This whole time I’ve been taking photos has been, really, trial and error. And sometimes not having the right equipment or having an old camera or having a crack in the camera or picking up a piece of cloth and putting it over the lens or experimenting with expired film because it was cheaper. All those things just lead to a hazy or dreamlike quality.

I will say for myself, I found some high ASA black and white film that had expired years ago. And I had that moment of thinking, what is this going to look like if I go and take some photos and get it developed and see what it looks like?

And how did it work out? It’s cool, right?

It worked out pretty well, yeah. I was expecting that I might get something that looked absolutely bizarre, but when I got it back, it just looked like film.

Yeah, exactly. I just used some old black and white medium format, 10-years-expired film and it turned out pretty great. It’s a little bit hazy, but…

Do you tend to focus more on the analog side of things or do you keep a balance between analog and digital?

I love film, I love the mystery and not seeing the results right away, but I have experimented with digital and I think it’s great just to have everything immediately. It’s just a different process of working. So I like both. I’m not strictly a film snob, but I do enjoy it more — it’s just so expensive.

Tell me about the new exhibit, PRISM. Is there one overarching theme, or is it more of a survey of your work?

It’s more of a survey of my work. As for the theme, I tried to tell a bit of a story — the outside and inside, landscapes, people, my mom, my friends, some self portraits and really just experimenting with light [and] developing processes.

That’s the common thread in my work. It’s just an experiment, it’s a journey. I’ve also been printing photos and then painting on top of them.

How long did it take you to go through the work that you’ve done to date and figure out what would and would not fit into this particular exhibit?

I’ve always been working on this. To some extent, for the last year or so, I’ve been putting together images for a book. So I had a general idea, but I’d say in the last month, it’s been crunch time to figure out how everything flows together. And the editing process is tricky.

It’s the hardest thing, to go through tons of images. Some of them just don’t fit with this particular narrative. So I would say in the last month, I’ve really had to focus and just do it.

Was there anything that you were drawing inspiration from as far as using a space and using the work within the space to tell a narrative?

Well, I’m really inspired by home — family albums and things that seem like a snapshot but do tell a story. So it’s like a mix of landscapes, and then body parts and some portraits. I’m inspired by different photo books that do that. I like work that is like a kind of time capsule. So, one story is just editing and going through and seeing what fits.

Earlier, you talked about landscapes. Are there any in particular that you’ve been particularly drawn to or that you’ve gone back to again and again?

A few years ago I was exploring abandoned buildings. I went to upstate New York and found this old theater. That was really cool. Yeah, I just snuck in and….

I like abandoned places, but it’s hard to shoot them in a way that doesn’t look cheesy or whatever. But I like roadside imagery — like headlights of cars. That always seems to be like a theme, because it’s just very cinematic — it reminds me of Lost Highway, by David Lynch. I think it all has to do with light and just a mood.

Are there any other abandoned buildings that you’ve been drawn to as far as a subject over the years?

I lived in Portugal for the last 10 years, and there was a really cool structure that was by my house, where all of these owls lived. It was totally crumbling and abandoned. I don’t have any of those images in this show, but it was a structure that I always wanted to do a project with, but now it just exists in my memory.

Were all the works in this show taken in the U.S., or is there work from your time in Portugal in there as well?

There’s a lot of work from my time in Portugal, and from going to Canada to visit. Portugal was an interesting experience because I was quite isolated. I basically lived in a small town an hour away from Lisbon. So I had a lot of time to work on photos of the experiment — a lot of the self portraits, especially because there was no one else around to see.

Has the way that you’ve photographed yourself evolved over the time that you’ve been doing that?

Yeah, for sure. I would say that it’s gotten more mysterious. I don’t really like to show that it’s me. I don’t like to have my face in the photos. And I don’t know, maybe that’s evolved. Maybe it’s just more abstract or has more of a painterly quality that I’m looking for. I’m less focused on the figure and the form and more interested in just if I’m there — I’ll use myself to make an interesting shape or whatever, as opposed to showing my identity.

When did you start experimenting with taking a photograph and then adding paint to it? Was that something that you’ve been doing since the outset?

About seven years ago, I got a bit bored of taking photos and I’ve always loved painting, I’ve always loved art. I decided to try painting just in general. I started with oil painting, it was really hard. It takes forever to dry, it’s super toxic, but I loved it. I started experimenting with watercolor and India ink and gouache, and then working in a really quick way.

I had a big painting obsession for a while and I still paint, but I thought it would be cool to combine the two mediums. So then I started making prints and then painting on top of them, just adding another element.

Is it challenging to find the right combination of materials so that the prints themselves look good but also work well as a surface for the paint?

For sure. You need to find really thick good quality matte paper, like photo paper. You have to have a very thin paint such as watercolor or gouache. You can control how opaque it is. You can add more water to the gouache and it becomes thinner and easier to work with. It’s trial and error.

When you’re working on printing a photograph, how does the sense of scale factor into that? Are you generally taking something that might be life-size and shrinking it, of keeping it life-size or making it much larger?

I’ve never really worked in large sizes, mostly because I didn’t have enough room in my studio. And that’s still the case. It’s still quite difficult to work with large prints, even though I would love to. And so I look forward to someday having a huge studio to make huge work, because I think it does change everything.

The fact that I’ve just used smaller prints, I think it works for when I’m adding when I paint on the photo, but I look forward to experimenting in the future when I have more resources and more space. It’s just hard to find space.

A Glimpse Inside Artist Erik Parker’s Neon Daydream

We toured Parker’s New York City studio to see how his bold, bright brushstrokes capture imaginative coolWhat do you hope people will take from going to see PRISM and experiencing it?

That’s a good question. I hope that they take whatever they want from it. I think art is up for interpretation, everyone has their own reaction to it and I think that’s beautiful. So if someone feels something at all, then that’s great. If they feel an emotional pull to the work, that’s my goal because I love art when it strikes you like that and there’s no explanation, but you just feel this connection.

You talked a little earlier about being inspired by Lost Highway. Are there any other films or books or pieces of music that you’ve drawn inspiration from over the years that are relevant to the show — or in general?

I love Wong Kar-wai’s In the Mood for Love, I love Three Colors: Blue. The Double Life of Véronique is my favorite movie of all time.

With Kieslowski, you also have that really interesting use of color, which I feel like I don’t really see in other films from that era — but I also don’t see it now. When I go back and watch those, it’s just so, so striking.

It’s so beautiful. And like the color — the way the emotion and the color are linked, which is beautiful. I love it. It’s a great quality.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.