“In 1971, the year that we set the beginning of The Deuce, I was 11 years old,” co-creator David Simon recalled. At 17, he spent the summer in New York while working at an uncle’s warehouse: “I can tell you that, while the city felt electric and volatile and amazing and, from its debauchery to its culture, it felt like an incredible place, it was also dangerous as hell.”

Times Square Alliance President Tim Tompkins echoed this: “Times Square’s always been about popular entertainment and always been on the edge of what is socially acceptable.”

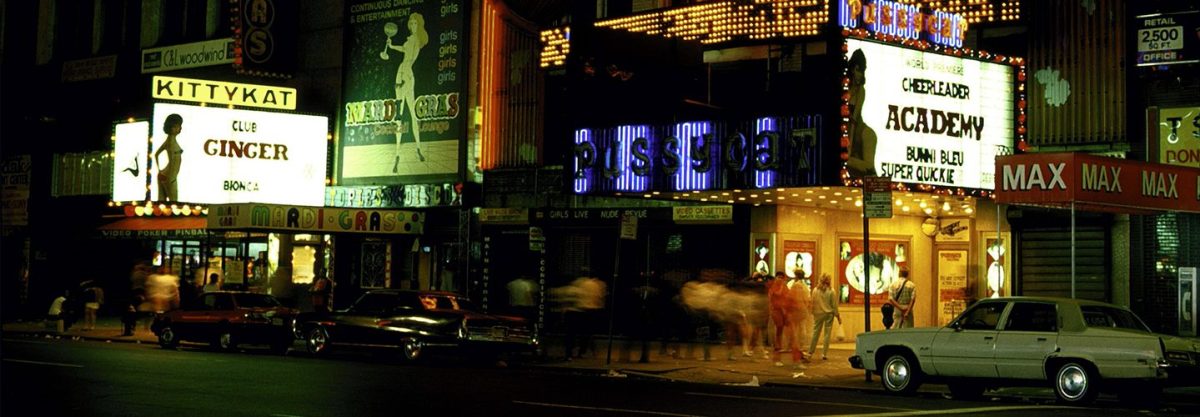

For many, “Times Square” instantly conjures images straight out of Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver. But Times Square existed long before then and, of course, is going strong today.

This is how Times Square became what it was in the 1970s and why those days are long gone. (For those who haven’t scanned a map of Manhattan recently, Times Square stretches from West 40th to West 53rd Street and Sixth to Eighth Avenue.)

To begin, here are some of the milestones that made the ‘70s incarnation possible.

1901: For those who think Times Square went to seed over time, you’re wrong: it started out quite seedily. Untapped Cities reports that Longacre (also known as Long Acre) Square and a few surrounding blocks were “home to 132 brothels and at least as many saloons.” There was also a showbiz presence, notably the massive theater complex known as the Olympia. (Owner Oscar Hammerstein was the grandfather of Oklahoma! lyricist and book writer Oscar Hammerstein II.) The theaters contributed to the area’s questionable reputation. As Tompkins noted, “Acting, until relatively recently, was viewed as this out-of-bounds profession.”

1904: On April 8, Mayor George B. McClellan (who served from 1904 to 1909) renamed Longacre Square to honor a newspaper that would soon move to the block. The name “Times Square” remained even after the New York Times itself moved.

1905: The IRT Times Square station began operations and had nearly five million passengers in its first year. To this day, Tompkins believes accessibility is key to the character of the area: “Times Square has always been this transit hub a zillion people pass through” making it “this spot where you can be anonymous.”

1907: This year saw both the first Ziegfield Follies—which Tompkins noted would eventually be performed over “glass balconies where patrons below could look up at the undergarments of the women”—and the first Times Square ball drop. (Incidentally, the ball currently drops from the original New York Times building.)

1914: The Mark Strand Theatre opened at the corner of 47th and Broadway. With roughly 3,000 seats, it was dubbed the first movie palace.

1929: The Great Depression hit. Like the rest of the nation, Times Square struggled to cope with the economic collapse, with the result it began to offer increasingly cheap thrills.

1931: The Minsky brothers opened the Republic Theater at 42nd and Broadway. Their burlesque house drew strippers including Gypsy Rose Lee. (William Friedkin later paid tribute to this period with his 1968 film The Night They Raided Minsky’s about an Amish girl who wants to be a dancer—really.)

1934: “There are these cycles of cleaning up,” Tompkins said. One occurred under Fiorello La Guardia (mayor from 1934 to 1945). It can be argued, however, that the Little Flower’s efforts didn’t get rid of the vices so much as get them out of view. (This will be a pattern in Times Square history.)

1941: The U.S. entered World War II. Times Square hosted one of the world’s most famous embraces, immortalized by Alfred Eisenstaedt’s iconic V-J Day photo “The Kiss.” (The war also witnessed soldiers on leave searching for more adult entertainments.)

1959: The Immoral Mr. Teas was released. Directed by Russ Meyer, it wasn’t the first film to feature extensive female nudity, but those generally presented themselves as explorations of “naturism” (a lifestyle that apparently consisted of being a woman with no clothes on). With the tagline “A French Comedy for Unashamed Adults!,” Meyer discarded any pretense of his film being educational. It was a massive hit, earning roughly $1.5 million on a budget of just $24,000.

1969: Pornography in Denmark rather ingeniously succeeded in getting shown in theaters by presenting itself as a “documentary” on pornography. (As opposed to just pornography.)

1971: Simon’s The Deuce enters the picture.

This was the moment right before Deep Throat, which was released on June 12, 1972, in New York City and may have earned as much as $600 million. Simon questioned the exact figure—“I don’t know what numbers to trust”—but readily conceded it “made money.” Indeed, considering its budget may have been as low as $25,000 and a single theater chain in L.A. showed it for an entire decade and earned $6 million, it made a frightening amount of it.

Just not “for the director or any of the people in it.”

So who got the payday?

Organized crime. “They were essential,” declared Simon. The mob “ran all the film labs” and “bankrolled all the films, all the major releases.”

Of course, the mob didn’t stop at a cinema and proved equally essential to “establishing the hide-in-plain-sight massage parlors that were all over Midtown.” Simon said the parlors can be attributed to the Lindsay administration’s determination to get “sleaze off the street.” John Lindsay (mayor from 1966 to 1973), like LaGuardia before him, wanted to clean up the neighborhood. And, like LaGuardia, his efforts ultimately meant little more than illicit activities moving indoors.

“This was a practical solution in that brief window he thought he could be president,” Simon said.

Police may have known they were shifting the problem rather than solving it. Simon said they were okay with this because the mob gave them a good reason to ignore what was going on: “They started paying cops in ’71, ’72 and they kept paying the cops until ’85, ’86 when they finally kicked the doors in.” (Simon said this occurred “because Ed Koch [mayor from 1978-1989] needed to close the gay bathhouses because of HIV. As a means of showing it wasn’t a political calculation, they simultaneously kicked in the massage parlors.”)

The Deuce covers many of the events from this time period. While partly fictionalized, some details that seem invented are actually true. For instance, the twins, both played by James Franco, actually did exist. (Simon said he is delighted by Franco’s double role—“I’ve never been more proud of a collaboration”—which became downright surreal when Franco played scenes opposite himself in episodes he also directed: “There were some moments director Franco would tell actor Franco what to do and actor Franco would start arguing with actor Franco #2 and then actor Franco #2 would then appeal to director Franco. We just had to leave the three of them alone for awhile to work it out.”)

It was a time when the city was electric, but Simon stated it wasn’t all partying at Studio 54: “There were a lot of bad outcomes for people. In no way am I trying to breathe nostalgia into a view of Times Square.”

Tompkins agreed with this outlook. He recognized the allure of the place back then—“Especially for gay folks, Times Square was a place of sexual freedom”—but added, “If you were a woman who was just trying to get from the Port Authority to your office, you were in serious danger.”

(My parents lived near Times Square in the ’70s. They very much enjoyed it until a neighbor went out for the Sunday morning paper and was killed during a robbery.)

This all leads to the question: What happened?

Let’s briefly return to the timeline.

1977: VHS came to America.

There was a moment when porn movies seemed like they were going to be actual movies. “It was going to become a coherent narrative form,” Simon said. “It was just going to become filmmaking with some fucking in it.” (He feels the Faust-inspired The Devil in Miss Jones—directed by the Deep Throat filmmaker, New Yorker Gerard Damiano—approached this ideal, terming it “almost good.”)

Then VCRs arrived. “Once it went back into people’s living room it went to the law of demand, it went right back to what it was originally: eight-to-ten minute loops that were solely male fantasy pieces, the more misogynistic, the better.”

This would eventually prove a deathblow to almost all porn theaters—New York still technically has one, albeit nowhere near Times Square. Under Rudy Giuliani (mayor from 1991 to 2001), Times Square experienced a Disneyfication as the sex shops were regulated.

It’s worth remembering the video and DVD stores didn’t go away completely: they just stocked enough “legit” movies so they could also sell porn. (The 60/40 rule allowed them to dedicate 40 percent on their space to adult content.)

Which brings us to the next event on the timeline.

1991: The World Wide Web was born.

The Internet ultimately wiped out a wide variety of stores, particularly adult ones.

Of course, porn is still around today. Why, when New York was at its epicenter in the ‘70s, is Los Angeles so clearly the industry capital today?

Simon thinks the answer is the mafia, though maybe not in the way you’d expect.

“I think the main reason is that the mob cannot run a legitimate business to save its life,” Simon said. “Once it became a legitimate business, it had to compete on legitimate terms, they f-cked it up like they f-ck up everything.” He noted the mob had famously lost control of its casinos despite those being “basically a license to print money”: “These fuckers can’t figure out how not to steal from it so they’ll bust out their own casinos.”

Quite simply, the mob tends to grab as much cash as quickly as possible, which usually doesn’t lead to lasting legit enterprises: “They’re terrible with paying people. They’re terrible at looking at the long-term viability of an industry. So with porn, they were shitty to people, they grabbed all the money they could in the short term. All for me, none for you.“

Enter L.A. “Ultimately, [the New York porn industry] went to the cast-offs of the film industry,” Simon said. “Those are people who know what to do, right down to, ‘Hey, we’re going to be shooting all day: somebody handle craft services.’ It’s as simple as that. Gambino can’t do that.”

Tompkins believes that changing social attitudes also altered Times Square, crediting “gay liberation and sexual liberation overall so people could express themselves somewhere other than a totally anonymous dark place.”

Of course, Tompkins noted the biggest change was an obvious one: “The crime situation got under control.”

Tompkins attributed this primarily to two things. “David Dinkins [mayor from 1990 to 1993] and Peter Vallone [Speaker of the New York City Council from 1990 to 2001] authorized a significant increase in funding for cops. That didn’t really take effect until Rudy Giuliani came in. And then Giuliani was much more aggressive about these smaller quality of life crimes in public spaces that made people uncomfortable.”

(Tompkins also said Times Square Alliance and similar organizations helped by focusing on the “small, down-on-the-ground quality of life things that contributed to people feeling safe or unsafe.” He noted how unsettling it could be for people to come to Times Square and, while not in any immediate danger, still find themselves surrounded by graffiti and three-card monte.)

Soon Times Square was very different indeed.

“When Disney came, it was feared the raucous spirit of Times Square was going to be tamed in some way,” Tompkins said. While acknowledging there’s a “legitimate concern about how you make sure it represents New York and stays authentic,” Tompkins remains optimistic for the future of Times Square: “No single corporate or political entity is going to be able to control it.”

The result is that the Times Square of the ‘70s often seems not just from a different era, but a different city entirely. And that’s fine with Simon: “As much as I might not want to patronize the chain logos of today’s 42nd Street, I don’t think anybody can sensibly wish 1977 back on Midtown Manhattan.”

[Additional reporting by Jason Lindner.]

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.