In 2002, John Kiriakou was helping the Central Intelligence Agency track Al-Qaeda suspects in Pakistan.

Ten years later, he was indicted on five felonies, including three violations of the Espionage Act.

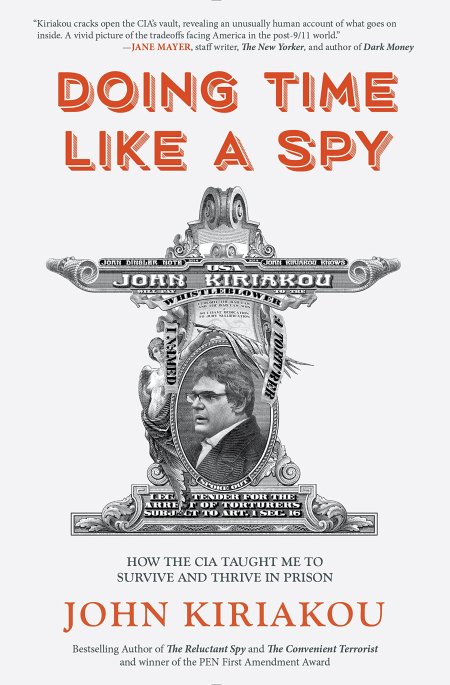

The counterterrorism-officer-turned-whistleblower turned the resulting ordeal into a book—out this week—Doing Time Like a Spy: How the CIA Taught Me to Survive and Thrive in Prison. And as Kirakou told RealClearLife in an exclusive interview, it took all his tradecraft skills to navigate a maximum-security facility crammed with vengeful guards, mobsters and violent prisoners.

Kiriakou says his CIA background taught him “to be more cautious than, I think, 99 percent of people would be. You constantly have to be aware of your surroundings and what’s going on.”

“I had to constantly be collecting information on people, on guards, on events just to make sure that everything went okay and that I was safe,” he added.

It all began with 2007 ABC News interview, the first time a government official had acknowledged the Agency’s use of waterboarding. “I had aired the CIA’s dirty laundry—something which, is not done,” Kiriakou said bluntly.

After an initial FBI inquiry didn’t yield an indictment, the former case officer’s case was re-opened without his knowledge and he was secretly investigated for three years.

Then, in 2012, charges were filed. Once the most serious charges were dropped, he pleaded guilty to disclosing the identity of an intelligence officer to a journalist and was sentenced to serve 30 months in prison.

Highlighting the fact that the Obama administration charged more people under the Espionage Act than previous presidencies combined, the ex-CIA officer says Obama had a “Nixonian obsession with national security leaks.”

“This was a decidedly Obama policy, to use the Espionage Act to charge political opponents,” Kiriakou says. “As bad as Donald Trump might be, I can’t imagine a Trump administration doing something similar, or any other administration… even George Bush didn’t.”

Trying to make the best of a bad situation, Kiriakou and his family planned to treat his sentence like one of his CIA deployments overseas—or a “TDY” as Kiriakou called them. But things didn’t go as expected, and he soon learned that politics don’t stop at the prison gates.

When he reported to Loretto Correctional Institution in February 2013, Kiriakou was placed in the high-security prison with the most violent offenders instead of the adjacent minimum-security work camp to which the judge had agreed to send him. By the time Kiriakou would be able to get a hearing for an appeal, his sentence would be nearly over.

After his release, through a Freedom of Information Act request, Kiriakou learned that his file included a warning that he had access to the media. He believes that getting placed in the higher security prison was designed to silence him.

“In fact, the opposite was true, if I had gone to the camp, I would’ve just kept my head down, kept my mouth shut; I would’ve done my time and I would’ve gone home,” said Kiriakou. “But because they did this to me, I decided to speak out.”

Kiriakou penned a series of letters from prison.The ex-CIA officer channeled his frustration into writing. His first letter—part of a series called “Letters from Loretto”— was published online and went viral. He then wrote a few op-eds that were published in The Guardian, the Los Angeles Times, and the Daily Beast. Before Kiriakou knew it, celebrities like John Cusack and Oliver Stone were championing his cause. He even got a call from Yoko Ono.

Kiriakou explains that while the writing and its reception outside the prison walls “invigorated” him, it “infuriated (the correctional officers) for two straight years.”

That led to daily harassment.

To endure that pressure and navigate prison politics, he fell back on his skills from his former employer. “In CIA operational training, a big part of it is learning how to manipulate people into getting them to give you what you want, and you essentially do the the same thing,” Kiriakou said. “You’re constantly working people.”

Whether it was refusing to call the guards “sir” or making friends with the right people, Kiriakou deftly worked the system.

For instance, he learned that he couldn’t be punished for writing as long as he didn’t name any of the guards in his letters. “I knew the rules better than they did,” he claimed.

His cell, however, would still get trashed from time to time.

His fellow inmates didn’t give him as much trouble. “I made some really great friends in prison,” Kiriakou recounted. Before he got there, someone who had been following Kiriakou’s case went around to various mafioso in the prison and explained the difference between the FBI and the CIA. “The Italians welcomed me with open arms,” he said. Members of the Gambino, Bonanno, Lucchese, Colombo, Genovese crime families became his “closest friends.”

But, when another inmate called him a rat, Kiriakou exploded violently and challenged the guy to fight him on the spot. “As God as my witness, I was going to tear this guy limb from limb,” he swore. Before anything could happen, Kiriakou’s friend, a captain in the Bonanno crime family, intervened and told him he’d “take care of it.” Just 20 minutes later, the accuser showed up at Kiriakou’s cell with “his face totally rearranged” and apologized to him.

If that didn’t sound like something from a mafia movie, Kiriakou says “every night” was like the dinner scene depicted in Goodfellas. They indulged in white wine and ate Italian sausages (both sweet and hot) served with homemade marinara sauce, cooked in garbage bucket with live electrical wire.

“I gained 15 pounds in prison,” he said. “The food was amazing.”

Doing Time Like a Spy: How the CIA Taught Me to Survive and Thrive in Prison, published by Rare Bird Books, is available May 16.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.