Brands using their advertising budgets to spar with their rivals is nothing new, but it may have reached its apex in the 1980s when Coca-Cola and Pepsi engaged in the “Cola Wars.” This piece of corporate and pop-cultural history included everything from celebrity endorsements to appeals to patriotism, and it’s been echoed decades later in subsequent marketing campaigns both in the world of beverages and in wildly different industries.

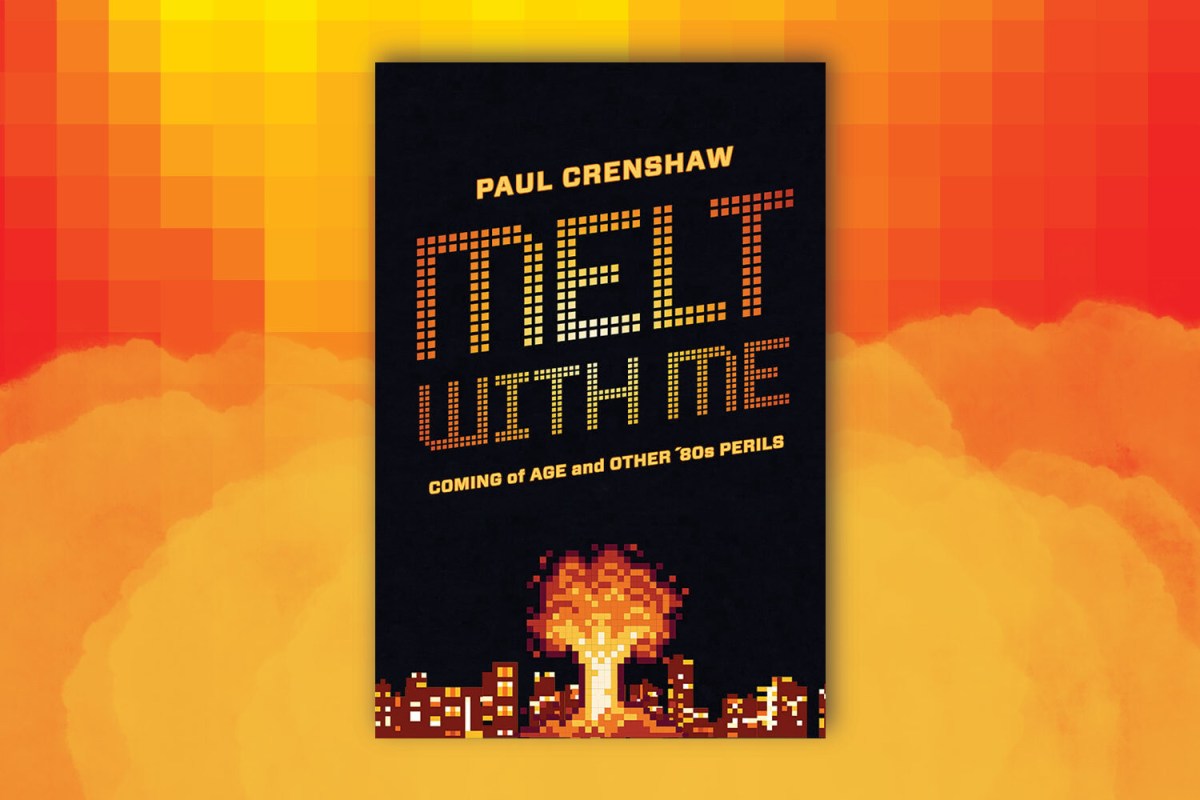

In this essay — excerpted from his new collection Melt With Me: Coming of Age and Other ’80s Perils — Paul Crenshaw looks back on the Cola Wars and the ways in which they intersected with his own growing awareness of the world. It’s one of several moments from that era that resonates throughout the book, with other essays dealing with everything from Star Wars to the Choose Your Own Adventure series of books.

This isn’t being done for the sake of pure nostalgia, though. Crenshaw has made several direct connections between the 1980s and the way we live now, both in his writing and in conversations about it. “I think the ’80s were death by a thousand cuts,” Crenshaw said in a recent interview. “It wasn’t one big incident, just constant little cuts.” Read on for a glimpse inside Paul Crenshaw’s youth and the pages of Melt With Me.

Cold Cola Wars

Kevin Sloak liked Pepsi, so I didn’t like Kevin Sloak. Heather Davis liked Pepsi too, and despite the fact that she had developed a crush on me, I couldn’t bring myself to like a girl who drank Pepsi because Pepsi was sold in the Soviet Union, which made Heather a traitor to everything we held dear in the summer of 1986, and it made Kevin-shitting-Sloak a communist.

We didn’t know then about the Kitchen Debates between Nixon and Krushchev, nor anything about unfettered capitalism. We didn’t know Pepsi had, in the early ‘60s, claimed to be of our parents’ generation, that it was one of the first companies to aim its marketing campaigns at lifestyles, and the lifestyle it aimed at in the ‘80s was us, the next generation. What we did know was that Coke wanted to teach the world to sing and that Pepsi had nearly killed Michael Jackson in 1984, as if they no longer wanted him to sing. We knew that instead of the cool Coke candle commercial, Pepsi constantly aired those stupid taste-tests on TV.

But what earned our unfettered ire was that besides being sold in the Soviet Union, Pepsi was their preferred drink. Even without the King of Pop disaster and the mind-numbing commercials appearing every eight minutes, the fact that communists drank it was reason to hate it. We’d been taught all through elementary school to fear everything Soviet, including, but not limited to, colas, and since Pepsi had manufacturing plants in Moscow and had signed an exclusive deal to distribute their soda to the Soviets and ship Soviet vodka here, we reasoned, as red-blooded Americans, it was our patriotic duty to not only boycott Pepsi, but to harass Kevin Sloak at lunchtime, where he sat on the front steps of the school with his sad papersack lunch.

“Pepsi even sounds Soviet,” I might have said, late summer of ‘86, to Kevin Sloak, with a few of my bigger friends looking on. “And so does Sloak.” But Kevin was one of those kids who wore a trenchcoat and fingerless gloves to school in August, and so kept his head down until we wandered off looking for easier fare, someone we could make cry because, it seems to me now, that was what we did in 8th grade in 1986. The world was always at war and so were we. Pepsi fought with Coke and the U.S. fought with the USSR and we all fought with each other because we couldn’t fight ourselves. Our bodies had morphed us into monsters and our faces had broken out from all the sodas we consumed and we hated everything about the time, even our own insides.

So we wandered off to another part of the steps, waiting for the bell to ring, where I would go to class and sit by Jennifer S., who drank Dr. Pepper, which was bottled by Pepsi in some places and Coke in others, and therefore a gray area. There was no internet then, so we didn’t know the whole history of the Cola Wars and the Cold War and how our own needs drove them both, nor did we know the name Pepsi-cola was an amalgamation of “dyspepsia” and “kola nuts,” but I’m sure we could have come up with something clever, like “stomach-nuts,” had we known.

#

How Suburban Chicago Became the Unlikeliest Clubbing Scene of the 1980s

For a few brief years, strip malls and chain restaurants gave way to cocaine and disco ballsIt began like this: on July 24, 1959, Soviet First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev drank a Pepsi. In a cultural exchange program designed to promote understanding between the two countries, the USSR held an exhibition in New York. The United States held their own in Moscow, featuring American products: cars, art, fashion and a model American house. A number of companies sponsored exhibits and booths, including IBM and Pepsi.

In the kitchen of the model house, then-Vice President Richard Nixon and Khrushchev discussed the differences in their countries. At one point, Nixon led Khrushchev to a display of Pepsi, one mixed with “American” water, the other with “Russian.” Khrushchev continually denigrated capitalism, but, as the story goes, he loved Pepsi.

And, as capitalism and politics so often collude, the idea to get Khrushchev to drink Pepsi came from an ad exec named Donald Kendall, who saw the Soviet Union as a vast new territory for Pepsi to conquer. It took Kendall over a decade to do it, but in 1972 he negotiated a deal to send Pepsi to the Soviet Union, where it would be bottled locally. He also locked out Coca-Cola, Pepsi’s biggest rival, until 1985. Pepsi became the first capitalist product available in the Soviet Union, but because the Russian ruble was worthless in Western markets and Soviet capital could not be used abroad, the United States got Stolichnaya vodka as a trade.

By the mid ‘80s, about the time I stomp angrily into the picture, antagonizing Kevin Sloak on the front steps of the high school, Soviets were drinking Pepsi almost as much as my friends and I stole our parents’ Stoli vodka. I suppose it didn’t occur to us what hypocrites we were to criticize Kevin for his Pepsi at the same time we skipped school to get soused on Stoli, but I’ll say here that with alcohol at that age, you take what you can get and let the finer points of boycotting fall to the side, much like you will do later, probably in a ditch somewhere.

I digress.

The problem with the Pepsi deal, besides our small-town paranoia of anything Soviet-made that didn’t contain alcohol, was that the Soviet Union couldn’t pay. The trading of vodka worked until more Americans began boycotting Soviet products over the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, hurting Pepsi’s profit of Stoli distribution, which meant that the Soviets needed to find a new means of exchange.

What they came up with were ships. In the spring of 1989, only a few months before I would join the military, the Soviet Union gave Pepsi 17 old submarines and three warships to keep their deal going. Pepsi eventually sold the warships. But for a brief moment, like the 15 minutes of fame we’re all supposed to get, Pepsi had the sixth largest navy in the world. Kevin Sloak still wore a trenchcoat to school, and possibly carried a switchblade. With the acne attacking him and the anger he wore around, we were afraid he might retaliate if we poked fun at his Pepsi. Michael Jackson had recovered fully and was now making commercials in Russia. Which meant that, despite the Berlin Wall coming down, it seemed as if the Soviet Union had won a different kind of war.

It did not seem odd to us in the ‘80s that two companies would feud over cola. Nor that a cola could represent a country we hated simply by associating with it. Perhaps it was because we were still kids or perhaps it was because of our culture and the Cold War, but it was easy to label what we didn’t like as different. Easy to claim as communist anything we didn’t understand, easy to call communism evil, easy to define a country with some derogatory term that fit our worldview, not knowing where we stood influenced us. It was so easy to hate Kevin Sloak, with his trench coat and fingerless gloves, sitting by himself on the front steps of the school, drinking his Pepsi-cola and eating his peanut butter sandwich with the crusts cut off. So easy to believe our social studies teachers, who had grown up fearing what might fall on them out of the sky. So easy to cling to conservatism and our choice of colas, so easy to see only the hills that ringed our small town. So easy to see only two choices and not the many we already own.

Coke eventually won the Cola Wars. The Soviet Union broke up in 1991, and Pepsi lost their exclusive deal. They kept parts of it together, but were dealing with multiple countries now instead of one. Their bottling plant was in Belarus. Their ships were stranded in the Ukraine, which wanted a share of the cut. Pepsi put up giant billboards in Pushkin Square, but Coke still got in, and after only a few years beat out Pepsi as Russia’s most popular soda.

We should have rejoiced. But by then our hatred toward others had turned to the Middle East. I gave up sodas altogether and went straight to vodka, which I drank while watching the Gulf War, worrying, once again, whether the end was coming. Soon I’d seen enough of war to be sick of it. I woke too many mornings hungover, wishing for Sprite and chicken soup, for my mother’s warm hand on my forehead, telling me everything would be all right. Then the war ended and we went back to work or school or lying alone in the darkness hoping the headache went away, knowing that it never would, that we would always fear the end of the world, that we would always be sick, would always need something like Sprite and chicken soup to heal our troubled souls, which may be why we cling so hard to the nostalgia of the past.

Coke wanted to be seen as wholesome and family-oriented, while Pepsi tried to appeal to the younger generation. They wanted to be the cool kids, to hang out with the Swatch watches and the acid-washed jeans and the feathered hair. Pepsi wanted us to see the world, but Coke said all we needed was right here. And since the world made us feel small and scared, we consumed our Cokes in the same way we swallowed conservative values. We held hard to the idea that the only way to win a fight was to build up our forces for the final battle. We held our hatred like rifles. We stoked our fear like fire and waited for the end, knowing God was on our side.

Thirty years later I found out Jennifer S. drank Pepsi. Her whole family did. Her father mixed his Canadian Mist with Pepsi, Saturday nights when his friends came over to play cards, and sometimes Jennifer stole a sip from it. I have to admit that when she told me this I felt a small twinge of betrayal. I called her a communist, but she understood the fear I felt, and so forgave me. The next day we went to a soda shop where she drank a Cheerwine and I drank a Big Red, neither of which are bottled by Coke or Pepsi. As if we had more than two choices. As if we could drink our sodas without fighting or fearing the end of the world. As if we could buy each other a coke, and drink it in perfect harmony.

This article appeared in an InsideHook newsletter. Sign up for free to get more on travel, wellness, style, drinking, and culture.