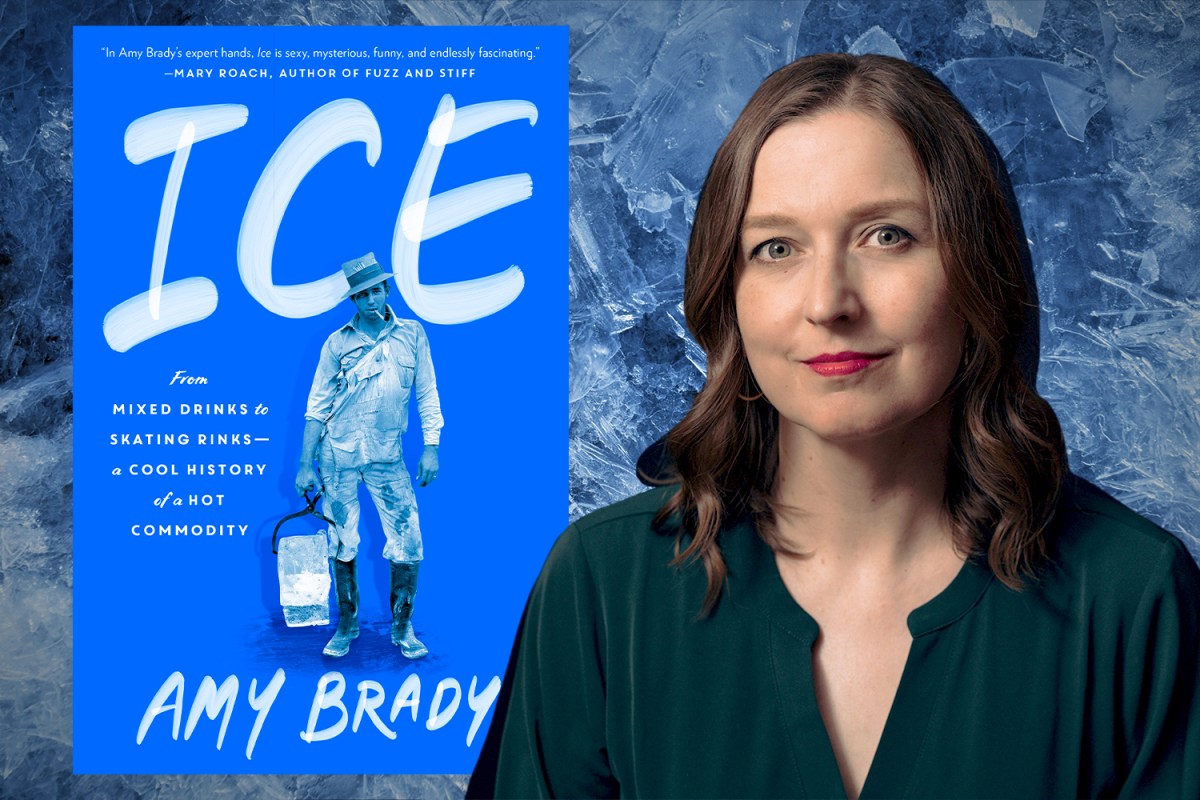

There aren’t many places where the rise of cocktail culture dovetails with scientists being accused of blasphemy — and yet when it comes to freezing ice on a warm day, that’s precisely what happened. In her new book Ice: From Mixed Drinks to Skating Rinks — A Cool History of a Hot Commodity, author Amy Brady chronicled the scientists, entrepreneurs and bartenders who took ice from a curiosity to something we can have in our drinks all year round.

That’s just a part of the story Brady is telling in this book, however. She’s also the co-author of a book of essays about climate change, and in Ice, she also explores both the environmental impact of having ice year-round and the scientific research which seeks to make this technology friendlier to the planet. Brady spoke with InsideHook about the process of researching icemaking history, why her book focuses on the United States and what role Prohibition plays in all of this. An edited version of our conversation follows.

InsideHook: Early on in Ice, you wrote about the idea of writing the book that you wanted to see out in the world. Was there ever a point where you entertained the idea of doing something more broadly on ice, or did you know from the outset that this book would focus on ice in the United States?

Amy Brady: I think from the beginning I knew it was going to be about ice in the U.S. I’ve had the fortune of doing some traveling in my lifetime. And when I’ve traveled to other nations where having ice in your drink isn’t typical, I’ve been looked at like something is growing out of my head when I’ve asked for ice in a drink.

I always had this suspicion that the American palette and taste for ice is somewhat unusual on the global scale. An impetus for this book was in part just to figure out why it is that Americans in particular are so obsessed with ice.

One of the most interesting things I learned from your book was the way in which the popularity of ice in the U.S. went hand in hand with the development of cocktails and cocktail culture. When you were researching Ice, were you surprised to be reading more about spirits than, say, academic history or science?

I ended up reading a lot more about booze than I anticipated. And I was not disappointed. I am not a trained bartender by any means, but I do enjoy a well-crafted cocktail as much as the next person. And to learn more about their history was a real pleasure. I will also say this, that as somebody who enjoys cocktails, I have been on a number of cocktail tours, including in early cocktail cities like New Orleans. And even those experts were surprised when I told them that the reason why their city was an early kind of groundswell for cocktails is because of the arrival of ice.

That connection isn’t a part of the city’s mythos. And I hope it becomes a part of the city’s mythos because it’s such an extraordinary moment in history and it transformed that city.

There was another moment when you wrote about the ideal ice for cocktails, and I remember thinking, “Oh, this is like in the bar Dutch Kills.” And then you went on to write about that bar’s business in ice-making for other establishments. Were they the only bar that you talked to that did that or is that something that other institutions like have dipped their feet into or or or embraced?

I’d have to look at my notes to tell you their names but there are a handful of bars that now have ice delivery on the side. You know there there is just this kind of Renaissance, if you will, of extremely clear ice being used in cocktails, both because it looks better and because it tastes better. And also, depending on how you source your ice and how you use it, it could be more sustainable. Again, it kind of just depends on your larger energy output as a business.

You’ve written a lot about climate change and the environment. And one of the things you bring up in Ice is the idea of getting ice-making tech greener and more environmentally sustainable. Was it a challenge for you to kind of find the right balance when writing enthusiastically about something that is not always the most environmentally friendly of practices?

Yeah, there’s definitely a tension there. And I think at least some readers will pick up on that tension in the book. As I admit in the introduction and in the conclusion, I’m obsessed with ice too. I love it. I love it in my drinks. I’m a fairly active person and I’m always injuring myself, and so having ice I can use on injured joints is really a necessity in my life.

At the same time, as I write in the book, the cooling industry, which involves refrigerators, freezers and air conditioners, makes up almost 10% of global carbon emissions, which is not a tiny chunk. And the majority of refrigerators that are made in the United States are now made with automatic ice makers, which actually increases the refrigerator’s energy drop, because they have to be powered on all the time. That’s why you can get ice, you know, at three in the afternoon or three in the morning.

Like many of my fellow Americans, I’m obsessed with something that is making the planet hotter. But that’s also why I wanted to devote space in my book to the people who are working to make the tech more energy efficient and the people who are calling for stricter government standards so that we’re capping the energy draw even as more and more people buy more and more refrigerators.

It also seems like there’s a paradox there: as the planet gets warmer, there’s a greater need for air conditioning, but that is itself contributing to climate change.

Our obsession with cold is the result of a planet getting hotter and it is also simultaneously making the planet hotter. It’s kind of like a snake eating its own tail.

Besides bars having ice-making sidelines, you also wrote about how different breweries used their facilities during Prohibition, including Anheuser-Busch making ice cream. Were there any other interesting uses of ice-making facilities during that time that really struck you?

Some of them became storage places for milk, because a lot of the big breweries are Midwestern and were not terribly far from cow farms and sheep farms. And so they became storage places. They also became ice storages for bars and restaurants that were opening soda shops. Many of them had speakeasies in the back, but they couldn’t legally sell alcohol. They opened up soda shops and at those soda shops, they made and sold ice cream, which requires an inordinate amount of ice to store and to create. And then they also wanted to serve their sodas over crystal clear ice. A lot of these places just didn’t have their own on-site ice machines or ice houses. And so they would get ice delivery from the breweries.

I’ve started seeing some coffee shops serve iced coffee with ice cubes that are themselves made from iced coffee. In your research, did you run across any other examples along similar lines?

I love that a liquid is its own coolant. I don’t know the specific history of coffee ice, but I can say that when the very first ice makers were being sold — and before that when the first ice boxes were being sold with ice cube makers or ice cube trays — they often came with recipe books for how to freeze interesting things in ice, which created more enthusiasm for the ice that people could use their machinery for. So the act of freezing things in ice goes way back to at least the 19th century.

What’s interesting about the coffee thing is, as the ice cube melts, you end up with just more coffee rather than dilution. And as somebody who loves, loves, loves strong coffee I love a frozen coffee cube, but it is a very specific approach and one that you wouldn’t necessarily find in a bar or restaurant that’s serving alcoholic drinks because ice has a very specific function in an alcoholic drink. It’s not just to cool the drink, but also certain types of cocktails need a certain degree of dilution to maximize their flavor.

Before reading Ice, I hadn’t been aware that some people accused the first scientists who figured out how to make ice of blasphemy. Beforehand, I had not thought at all about the theological implications of it, but that news spun my head.

When the announcement was made that a man had invented ice in Apalachicola, Florida, a place where ice rarely, if ever, forms naturally because it’s so warm there, there were newspaper headlines, up and down the Eastern seaboard saying that there was this crank doctor down in Florida who thinks he can make ice better than God almighty. He lost his reputation and died relatively early and penniless and greatly in debt.

This Is the Ultimate Guide to Clear Ice

“The Ice Book” makes transparency easy for home bartendersWhere did you find yourself going to research this? You wrote about some of the places you visited in the book. But it doesn’t seem like there is an obvious place to go, like a research library of ice or something.

I wish there was that. No, I would say I went all over the place to all different types of historical sites and archives. I have three favorites. One of my favorites was the library at Harvard, where in their archive they keep the diary of Frederick Tudor, who was the Bostonian madman who decided to sell ice out of his Massachusetts lake to warm climates, including the Southern U.S. states and territories.

It was amazing flipping through that diary. In the story that I tell, he was a very kind of brash and confident man. That’s how he came across to other people. But in his diary, he was wracked with doubt. And at one point, he’s writing in all capital letters, just ANXIETY, which I related to very much. He kept failing. And so when he finally succeeded, he wrote about that in his diary. It was interesting to see the psychological trajectory that he went on.

The other place was to Apalachicola, to the site where Dr. John Gorrie, the memorial for him, recognizing the invention of mechanically made ice. And it is more of a roadside attraction than a proper museum. It’s a very tiny little place, but I am delighted that they have a space dedicated to a man who did not get much positive recognition in his lifetime. It was heartening to see.

My third favorite place was actually going to the Budweiser brewery. I wanted to see the original site where they had kept the ice, and they still keep their brewing equipment and their refrigerators down there. It was really great being able to see that in person.

How has researching and writing this book changed the way that you look at ice, the way that you consume ice and make ice?

For one, I actually have learned how to turn off my ice maker, so it’s not running all the time. So it has gotten me to be more energy conscious. It has also renewed my sense of gratitude for modern-day life. Before writing this book, ice was something I never really noticed unless I’d run out. It was just something that was just always there and kind of in the background. It was an invisible commodity.

Now, I’m very aware of my ice use everywhere I go. I often think of all the people and the systems that had to exist over time to make that possible. And I’m immensely grateful for it. It fundamentally changed, not just our cocktails, but how we practice medicine. It greatly reduced instances of food poisoning, which was very common before folks figured out how to preserve food with ice, especially in children. I’m just really grateful for all of that history and to be the beneficiary of it.

Every Thursday, our resident experts see to it that you’re up to date on the latest from the world of drinks. Trend reports, bottle reviews, cocktail recipes and more. Sign up for THE SPILL now.